Why Is the Federal Reserve Special — and Just How Special Is It?

Although the arguments in Cook are important, the argument that Trump did not make — and the reason he did not — may be more important.

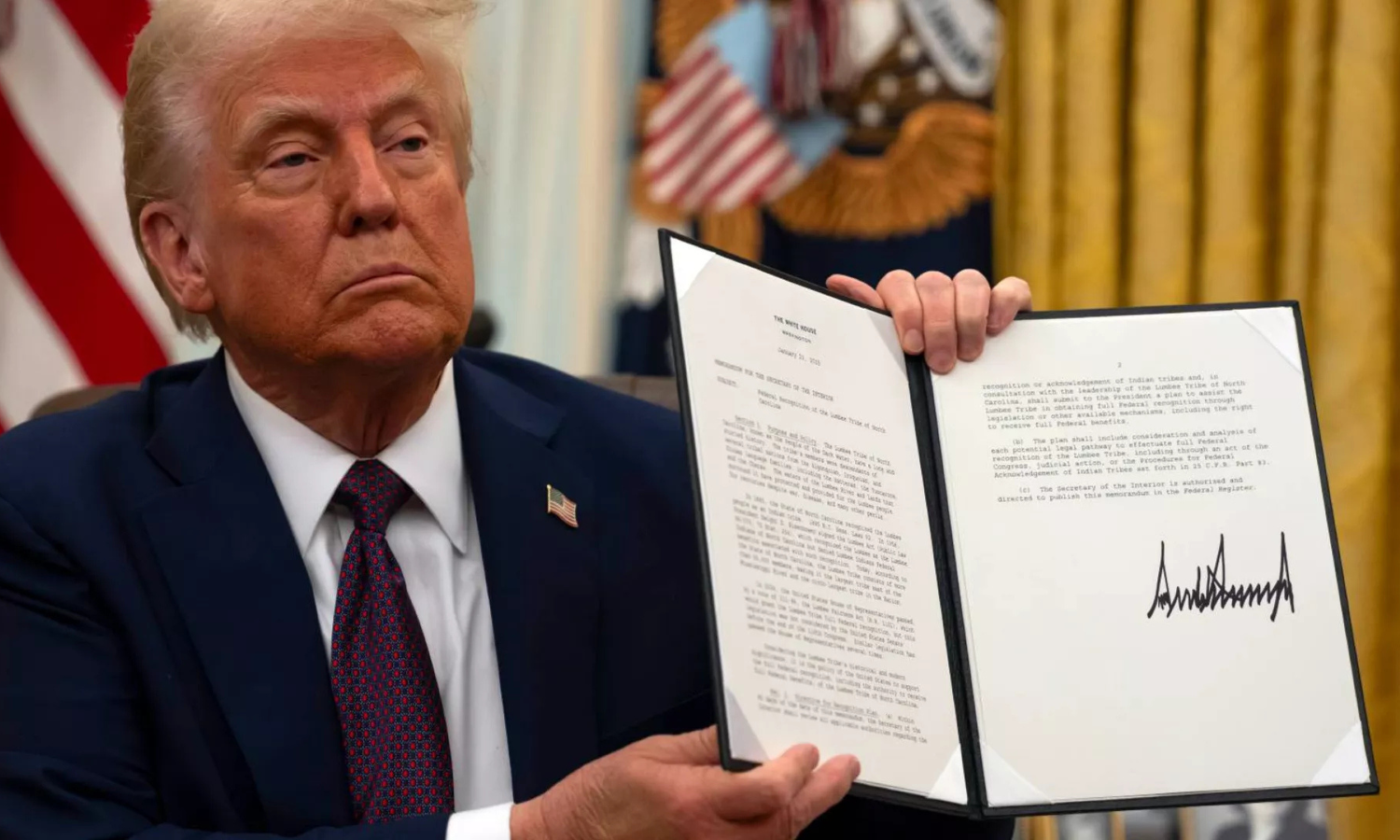

Tomorrow, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral argument in one of the most important cases of the term: Trump v. Cook. Cook asks whether President Trump had sufficient “cause” — the standard set by Congress — to fire Lisa Cook from her position as a Governor of the Federal Reserve Board. To justify firing her, Trump cited allegations of mortgage fraud. But some fear that if the standard removal is not very demanding, presidents will be able to influence monetary policy by threatening Fed Governors. Indeed, Cook argues that her alleged mortgage fraud is pretextual. Trump, of course, disagrees.

What is perhaps most noteworthy about Cook, however, is an argument that Trump has not made — that Article II of the U.S. Constitution supersedes any statutory restrictions on his ability to fire Cook. If the Constitution gives him authority to fire agency heads, why should anyone care whether Trump also had statutory authority? Either way, Cook would be out of a job.

Trump’s decision not to make a constitutional argument is even more noteworthy because such an argument could be made. After all, the Court has already held that Article II allows presidents to fire agency heads, and it appears likely that the Court will double down on that view in another important case this term: Trump v. Slaughter, which concerns the Federal Trade Commission. Following the Slaughter oral argument last month, it is difficult to find anyone who believes the Court will not allow presidents to fire FTC commissioners for policy disputes.

The Court’s separation-of-powers cases over the last fifteen years (mostly written, notably, by Chief Justice John Roberts) are very skeptical of the “headless fourth branch of government.” Much to the dismay of those who favor independent agencies (that is to say, agencies independent from the President), the Court’s majority believes that without the power to fire agency leaders, “the President could not be held fully accountable for discharging his own responsibilities; the buck would stop somewhere else.” The Court thus has stressed that under Article II’s expansive language, “‘the executive Power’ — all of it — is ‘vested in a President,’ who must ‘take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.’” And if that constitutional language were not enough, the Court has also emphasized that, as early as 1789, James Madison argued that this presidential power exists.

So why doesn’t Trump argue that Article II also authorizes him to fire Federal Reserve Governors? In other words, why is Cook a statutory case rather than a constitutional one?

There are at least two related answers, one based on law and another on strategy. As for law, the Court said earlier this year in an emergency order allowing the President to fire members of the National Labor Relations Board and the Merit Systems Protection Board that the Fed is different in kind because it “is a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second Banks of the United States.” Given that language, Trump’s lawyers no doubt recognize that the best strategy is to avoid constitutional arguments in Cook.

But the Court’s observation that the Fed is different from other agencies raises its own questions. For example, did the Court create a bespoke carveout from the Constitution for the Fed because the Court is afraid to follow its own logic?

For decades, the first argument advanced by supporters of independent agencies has been that the Court should not read Article II as Madison read it, because doing so would spell the end of independent monetary policy. As Justice Elena Kagan explained in dissent from that emergency order mentioned earlier:

The majority closes today’s order by stating, out of the blue, that it has no bearing on “the constitutionality of for-cause removal protections” for members of the Federal Reserve Board or Open Market Committee. I am glad to hear it, and do not doubt the majority’s intention to avoid imperiling the Fed. But then, today’s order poses a puzzle. For the Federal Reserve’s independence rests on the same constitutional and analytic foundations as that of the NLRB, MSPB, FTC, FCC, and so on …. If the idea is to reassure the markets, a simpler — and more judicial — approach would have been to deny the President’s application for a stay ….

Is she right?

I’ve been thinking about that question for a long time, and Kagan is mostly wrong, and the Court’s majority is mostly right. The Fed’s independence does not “rest[] on the same constitutional and analytic foundations” as other agencies. And the difference is (as the Court’s majority explained) that, in fact, the Fed is a “uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second Banks of the United States.”

In 2024, Aditya Bamzai and I published an article entitled "Article II and the Federal Reserve," which applies the Court’s Article II precedent to the Federal Reserve and explains the Federal Reserve’s unique history. I also filed an amicus brief in Cook. Many of the points in this essay are set forth in greater detail in that article and brief.

In the early days of the Washington Administration, Alexander Hamilton recognized the importance of independent monetary policy. In his 1790 Report on a National Bank, for example, Hamilton warned that manipulating currency “is an operation so much easier than the laying of taxes, that a government, in the practice of paper emissions, would rarely fail in any such emergency, to indulge itself too far in the employment of that resource, to avoid, as much as possible, one less auspicious to present popularity.” He thus proposed what became known as the First Bank of the United States, which he believed should be “under a private not a public direction,” precisely because elected officials may not always have the best incentives with respect to managing money.

The First Bank — and then the Second Bank — were peculiar entities. Although they performed functions such as assisting with tax collection and paying the federal government’s bills, they were not organized as a federal agency. Instead, like regular banks, they had private shareholders. Most of their directors came from the private sector, too. If these banks were part of the federal government, such a structure obviously would have been unconstitutional. After all, whatever one thinks of the President’s power to fire agency heads, no one disputes that Article II empowers the President to appoint them. Yet although the President appointed a handful of the bank directors, he did not appoint the bank presidents.

What’s more, as helpfully explained by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, these banks’ “prominence” and “broad geographic position in the emerging American economy allowed” them “to conduct a rudimentary monetary policy.” Specifically, by strategically managing bank assets, bank leaders could “slow the growth of money and credit” by effectively “putting the brakes on state banks’ ability to circulate new banknotes.”

In other words, during the same early decades in our nation’s history that Congress was not enacting restrictions on the president’s ability to fire agency heads, Congress was creating banks that the president could not control. By itself, this is strong evidence that monetary policy is a different type of animal.

More evidence, however, supports that conclusion. More than 200 years ago, for example, the Supreme Court opined on the constitutional status of the First and Second Banks. The Court reasoned that although the federal government “held shares in the old Bank of the United States,” it did not follow that “the privileges of the government were … imparted by that circumstance to the Bank.” Instead, the Court explained, the federal “government, by becoming a corporator, lays down its sovereignty, so far as respects the transactions of the corporation, and exercises no power or privilege which is not derived from the charter.”

As Bamzai and I explain, that analysis, standing alone, is incomplete. No one thinks, for example, that Congress could turn the Department of Justice into a “corporation” to prevent the President from controlling it. Commentators during this period, however, filled in the missing piece. As James Kent explained in 1827, “[a] bank, created by the government, for its own uses, and where the stock is exclusively owned by the government, is a public corporation,” while “a bank, whose stock is owned by private persons, is a private corporation, though its objects and operations partake of a public nature.” And as described by Joseph Angell and Samuel Ames in their early treatise on corporations, a legislature could not hand off “political” power to a corporation, but banking was not such a power.

This history matters because monetary policy overwhelmingly is the reason people today worry about the Fed’s independence. The Federal Reserve has a complex organizational structure, but a key component is private involvement through the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks. By statute, the Federal Reserve Banks are represented on the Federal Open Market Committee, which helps set national monetary policy through, among other things, open market operations — that is to say, the buying and selling of securities. Thus, at least for some of what the Federal Reserve does, the First and Second Banks are useful analogies. That is why the Court’s majority is not wrong to recognize that the Fed is unlike other agencies. The most important thing the Fed does has always been treated differently.

So why do I say that the majority is only “mostly” right? Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve today does much more than just monetary policy. And even how the Fed conducts monetary policy today may involve more than just open-market operations. In fact, Congress has increasingly tasked the Fed with duties like those of regulatory agencies. As a particularly stark example, Congress has enacted laws requiring the Fed to partner with other agencies to engage in the very sorts of regulation that the Court already has held requires presidential control.

Those extra functions create a problem. Just because not everything the Fed does requires plenary presidential control under the logic of the Court’s cases does not mean that nothing it does requires such control. To make the point plain, Congress could not transfer all the powers of the Department of Justice to the Fed and expect the President not to be able to control how those powers are exercised, including by firing those who use those powers in ways the President does not approve. Placing powers that presidents must control and powers that presidents need not control in the same hands is a recipe for disaster.

At some point, unless Congress acts (which would be preferable), the Court may be required to determine how to exercise the Federal Government’s powers that require presidential control. If that day comes, I suspect the Court will hold that Congress violated the Constitution by placing such powers in the Fed and conclude that those powers are “severed” from the statutory scheme so long as they remain lodged in the Fed. Such analysis will require the Court to decide much more granularly than it has to date, which powers require presidential control and which don’t.

Because Cook asks the Court to decide what “cause” means rather than what Article II requires, I do not expect the Court to wade too deeply into the history of independent monetary policy during the Cook oral argument. But given Slaughter, we know the Court is considering what Article II means for the Fed. Indeed, during the Slaughter oral argument, Justice Brett Kavanaugh asked Solicitor General John Sauer to confirm that a ruling against Slaughter would not threaten the Fed. I will be surprised if that exchange does not appear in a written opinion.

In real time, we are watching the Court reform the administrative state. Given the Fed’s importance, the Court is mindful of the implications of those changes for monetary policy. Thus, although the arguments in Cook are important, the argument that Trump did not make — and the reason he did not — may be more important.

Aaron L. Nielson is a senior fellow at the Civitas Institute and holds the Charles I. Francis Professorship in Law at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law.

Constitutionalism

Amicus Brief: Hon. William P. Barr and Hon. Michael B. Mukasey in Support of Petitioners

Former AGs Barr and Mukasey Cite Civitas in a SCOTUS Brief

Rational Judicial Review: Constitutions as Power-sharing Agreements, Secession, and the Problem of Dred Scott

Judicial review and originalism serve as valuable commitment mechanisms to enforce future compliance with a political bargain.

State Courts Can’t Run Foreign Policy

Suncor is also a golden opportunity for the justices to stop local officials from interfering with an industry critical to foreign and national-security policy.

Supreme Court tariff ruling should end complaints that justices favor Trump

John Yoo writes on the Supreme Court’s decision on President Trump’s tariff case.

Trump’s Tariff Tantrum

Trump leaps from the frying pan into the fire in the aftermath of Learning Resources v. Trump.

The Administrative State’s Sludge

Congress has delegated so much power across so many statutes that it’s hard to find a question of any public importance to which some agency cannot point to policymaking authority.

.avif)

.webp)