United States v. Lopez at 30: The Court’s Federalism Revolution Didn’t Happen

Thirty years later, What happened to Lopez?

Three decades ago, the U.S. Supreme Court decided United States v. Lopez and held that Congress exceeded its authority under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Soon after the decision, observers on both the left and right wondered whether Lopez would be a constitutional game-changer. One commentator colorfully stated that the Court had just “[g]un[ed] [d]own the Commerce Clause.” At the same time, another heralded Lopez as “a revolutionary and long overdue revival of the doctrine that the federal government is one of limited and enumerated powers.” And a federal appellate judge proclaimed that “Lopez is a landmark, signaling the revival of federalism as a constitutional principle, and it must be acknowledged as a watershed decision in the history of the Commerce Clause.” In short, many believed that Lopez would “redefine[] the nature of the Federal Government.”

That has not happened. In fact, last month, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit applied circuit precedent to reject a Commerce Clause challenge to a statute barring felons from possessing firearms. Concurring, Judge Don Willett explained that precedent holds that the Constitution is satisfied so long as prosecutors prove “that a firearm was manufactured in one State and later discovered in another,” and that the Supreme Court has suggested that “a defendant need not even know the firearm ever crossed state lines.” Willett wondered whether such a rule “honors the principle of enumerated powers.”

So, what happened to Lopez?

To answer, it is important to understand what the Constitution says and what Lopez’s holding is. On its face, the Constitution creates a federal government of limited powers. Section 1 of Article I of the Constitution provides: “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.” “Herein granted” is important language; the Constitution does not vest all legislative power in Congress. As James Madison explained in Federalist No. 45, “[t]he powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the federal government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State governments are numerous and indefinite. The former will be exercised principally on external objects, as war, peace, negotiation, and foreign commerce.” Thus, Madison reassured the founding generation that “[t]he powers reserved to the several States will extend to all the objects which, in the ordinary course of affairs, concern the lives, liberties, and properties of the people, and the internal order, improvement, and prosperity of the State.”

One legislative power vested in Congress, however, is the authority to regulate interstate commerce. The Commerce Clause provides that Congress may “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.” Furthermore, the Necessary and Proper Clause provides that Congress may “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers.”

Despite Madison’s prediction in Federalist No. 45 that “[t]he regulation of commerce” should be a power “which few oppose, and from which no apprehensions are entertained,” that sparse constitutional language now provides the grounding for huge swaths of federal statutory law. And for centuries, jurists have debated the meaning of these clauses. If read narrowly, Congress has less power to enact legislation. If read broadly, Congress’s authority increases. And if they are read as limitless, then Congress—despite lacking a “police power”—would have even more legislative authority than the States. After all, the Constitution provides that valid federal legislation may preempt (that is to say, supersede) state law. Under the Supremacy Clause, “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof … shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” Thus, although Congress only has certain vested powers, if it has a power, that power can be exclusive.

The scope of Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce is significant with respect to criminal law. Because they have general police powers, the States have primary authority to criminalize and punish conduct within their borders. And history teaches that few issues are more important to voters than criminal law and related issues — indeed, it often ranks near the top. As Alexander Hamilton explained in Federalist No. 17:

There is one transcendent advantage belonging to the province of the State governments, which alone suffices to place the matter in a clear and satisfactory light — I mean the ordinary administration of criminal and civil justice. This, of all others, is the most powerful, most universal, and most attractive source of popular obedience and attachment. It is that which, being the immediate and visible guardian of life and property, having its benefits and its terrors in constant activity before the public eye, regulating all those personal interests and familiar concerns to which the sensibility of individuals is more immediately awake, contributes, more than any other circumstance, to impressing upon the minds of the people, affection, esteem, and reverence towards the government.

If Congress too can create broad bodies of criminal law (and thus, like the States, gain the same “affection, esteem, and reverence” from voters), then candidates for federal office also rationally will run on such issues, which (from their perspective) presumably are more salient with voters than the issues upon which Congress undoubtedly can act, such as “establish[ing] Post Offices and post Roads,” creating lower federal courts, or “securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

Today, we have a vast body of federal criminal law, much of which overlaps with state law, and most of which rests on Congress’s Commerce Clause and Necessary and Proper Clause powers. Indeed, Congress’s express powers to create criminal law are limited to offenses such as counterfeiting and piracy. By expanding the number and breadth of issues that Congress can address, moreover, Congress’s ability to focus exclusively on issues within federal authority is presumably diminished. Congress has limited resources, so the more time it spends on one problem, the less time it can spend on others.

For a time, the Court prevented Congress from creating a massive federal criminal code. Chief Justice John Marshall observed in 1821 that Congress “has no general right to punish murder committed within any of the States,” and that it is “clear … that Congress cannot punish felonies generally.” Even apart from criminal law, the Court long rejected efforts by Congress to advance a broad reading of federal commerce authority. In 1870, the Court reasoned that the Commerce Clause “has always been understood as limited by its terms; and as a virtual denial of any power to interfere with the internal trade and business of the separate States.” And in 1921, the Court stressed that “[i]t is settled … that the power to regulate interstate and foreign commerce does not reach whatever is essential thereto,” and “[w]ithout agriculture, manufacturing, mining, etc., commerce could not exist, but this fact does not suffice to subject them to the control of Congress.”

Things changed during the New Deal. Although sometimes continuing to pay lip service to the notion that the federal government is one of limited powers, the Court indicated by deed that Congress’s authority under the Commerce Clause is all but infinite. For example, in Wickard v. Filburn, the Court held that Congress could regulate growing wheat for personal use on one’s own farm because such production, when aggregated with other farmers’ crops, could substantially affect interstate markets. But if that is the rule, in what sense does Congress have limited powers?

Then came Lopez in 1995, which marked the first time in nearly sixty years that the Supreme Court concluded that a federal statute exceeded Congress’s Commerce Clause authority. The case arose after a high school student in San Antonio brought a concealed handgun to school. Prosecutors indicted him under the federal Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990. Lopez challenged the act’s constitutionality, arguing that Congress cannot regulate simple gun possession near schools, which (he argued) was not commerce at all, let alone interstate commerce.

Surprising many, the Supreme Court agreed. Chief Justice Rehnquist’s majority opinion re-emphasized the rule from “first principles” that the Constitution creates a federal government of limited and enumerated powers, and that Congress (unlike the States) has no “general police powers.” The Court identified three categories of permissible interstate lawmaking: Congress may regulate and protect (i) the channels of interstate commerce (e.g., highways or telephone lines), (ii) the instrumentalities of interstate commerce (e.g., ships or airplanes), and (iii) activities substantially affecting interstate commerce (e.g., running “inns and hotels catering to interstate guests”). None captures merely possessing a gun in a school zone. The activity was non-economic, and the federal government’s theories that guns near schools “threaten[] the learning environment,” which in turn harms the national economy because of “a less productive citizenry,” were too attenuated. As the Court explained, “if we were to accept the Government’s arguments, we are hard pressed to posit any activity by an individual that Congress is without power to regulate.”

In dissent, Justice Breyer argued that “[u]pholding this legislation would do no more than simply recognize that Congress had a ‘rational basis’ for finding a significant connection between guns in or near schools and (through their effect on education) the interstate and foreign commerce they threaten.” As he saw it, the Court should not “restrict Congress’ ability to enact criminal laws aimed at criminal behavior that, considered problem by problem rather than instance by instance, seriously threatens the economic, as well as social, well-being of Americans.”

Following Lopez, the Court decided United States v. Morrison in 2000, which concerned the Violence Against Women Act. The plaintiff alleged that two university football players raped her and sought damages under that federal statute. Invoking Lopez, the defendants argued Congress lacked authority to criminalize such non-economic conduct. The Supreme Court again concluded that Congress exceeded its constitutional authority. Chief Justice Rehnquist’s majority opinion explains that gender-motivated violence is not (or at least need not be) economic activity that falls within Congress’s power, even when aggregated. As he explained, Marbury v. Madison holds that “[t]he powers of the legislature are defined and limited; and that those limits may not be mistaken, or forgotten, the constitution is written.” Although Congress made extensive findings showing that such violence imposes nationwide economic costs, the Court characterized the posited causal chain — violence affecting victims, victims affecting productivity, productivity affecting commerce — as “attenuated” and “unworkable if we are to maintain the Constitution’s enumeration of powers.”

After Morrison, it looked even more certain that the Supreme Court would enforce limits on Congress’s authority. If Congress cannot protect women from violence— a goal everyone should support (though obviously one that States too can pursue through criminalization and punishment) — then why couldn’t all sorts of federal statutory law be challenged?

Yet since Morrison, successful Commerce Clause challenges have been few and far between. True, in Bond v. United States, the Court interpreted a chemical-weapons statute narrowly to prevent turning ordinary local conduct into a federal crime, emphasizing federalism. And in NFIB v. Sebelius, the Court held Congress cannot use the Commerce Clause to compel individuals to engage in commerce by purchasing health insurance. Yet courts continue to hold that Congress can regulate possession of certain items. For example, after Lopez, Congress amended the statute to add what is called a “Commerce Clause hook,” which makes it a crime to possess a gun in a school zone if the firearm had moved in or otherwise affected interstate commerce. The upshot? “Lopez does not meaningfully constrain congressional power … even to regulate guns in or near schools.”

Furthermore, in Gonzalez v. Raich, decided in 2005, the Court upheld Congress’s authority under the Commerce Clause to prohibit local cultivation and use of marijuana. Plaintiffs grew marijuana for personal use and argued that federal enforcement of criminal laws prohibiting such cultivation exceeded Congress’s power. The Court, in a majority opinion by Justice Stevens and joined by Justice Scalia (who had been in the majority in Lopez and Morrison), rejected the argument and emphasized — echoing Wickard — that Congress may regulate such activity when, in the aggregate, it substantially affects interstate commerce. The Court distinguished Lopez and Morrison, noting that marijuana is part of a national market, so local cultivation could impact supply, demand, and prices nationwide.

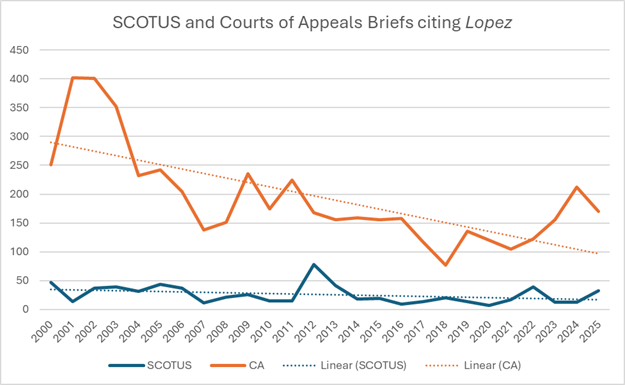

Judge Willett’s recent concurrence notwithstanding, I sense that those involved in federal litigation have largely moved on from Lopez. Indeed, Professor Jason Mazzone uses Lopez as his key example to illustrate that “efforts to create a strong line of doctrine might not succeed.” To test myself, I tasked a research assistant to use Westlaw to collect citations to Lopez in appellate briefs since 2000, and this is what he found:

To be sure, this data may be incomplete. Assuming it is at least mostly accurate, the trend line is clear. Apart from bumps around the time of Morrison and Sebilius, the citation count has held steady or has fallen over the decades, even though the U.S. population is approximately 75 million greater today than in 1995.

Furthermore, although there are successful constitutional challenges, Lopez is most often cited (if at all) by concurring or dissenting judges. For example, sounding a theme like Judge Willett’s, Judge Jim Ho of the Fifth Circuit observed in dissent from denial of rehearing en banc a few years ago that “[i]t’s hard to imagine a more local crime than” possessing two shotgun shells. And a judge on the Second Circuit similarly argued that “[i]n prohibiting violence against worshippers at places of religious worship, [federal law] regulat[ing] local, non-economic conduct that has at best a tenuous connection to interstate commerce.” But there has not been an avalanche of cases siding with constitutional challengers.

So, what’s the takeaway? For good or ill, Lopez has not revolutionized the scope of federal power. There still is a vast body of federal law, including federal criminal law. Of course, the threat of Lopez may have discouraged the passage of certain laws. But that also appears doubtful; a 2022 study shows that Congress has enacted hundreds of new crimes since 1995. That said, the Court indirectly has strengthened the separation-of-powers principles motivating Lopez. For example, countless federal regulations are backed by criminal penalties. The Court’s decision last year in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo to overrule Chevron deference thus presumably reduces, on net, the amount of private conduct that violates federal criminal law. And the Court also now regularly reads broad federal criminal statutes narrowly.

Such indirect efforts, however, plainly are not what many believed would result from Lopez and Morrison.

Perhaps the Court one day will extend Lopez. Or perhaps the Court will continue to defer to Congress’s judgment on the scope of federal power under the Commerce Clause. Either way, it seems safe to say that three decades in, “[t]he Court’s federalism revolution seems to have gone out with a whimper.”

Aaron L. Nielson is a senior fellow at the Civitas Institute and holds the Charles I. Francis Professorship in Law at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law. He has served three terms as a public member of the Administrative Conference of the United States. Before joining the faculty, Professor Nielson served as Solicitor General of Texas, where he argued five cases in the U.S. Supreme Court and oversaw all appellate litigation for the State of Texas.

Constitutionalism

Amicus Brief: Hon. William P. Barr and Hon. Michael B. Mukasey in Support of Petitioners

Former AGs Barr and Mukasey Cite Civitas in a SCOTUS Brief

Rational Judicial Review: Constitutions as Power-sharing Agreements, Secession, and the Problem of Dred Scott

Judicial review and originalism serve as valuable commitment mechanisms to enforce future compliance with a political bargain.

Supreme Court showdown exposes shaky case against birthright citizenship

Supreme Court will hear challenges to Trump's order ending birthright citizenship, testing the 14th Amendment's guarantee for babies born in America.

Trump’s Tariff Tantrum

Trump leaps from the frying pan into the fire in the aftermath of Learning Resources v. Trump.

The Administrative State’s Sludge

Congress has delegated so much power across so many statutes that it’s hard to find a question of any public importance to which some agency cannot point to policymaking authority.

.avif)

.avif)

.webp)