How Climate Litigation Imposes Back Door Carbon Taxes

A backdoor climate tax, the ultimate aim of the climate lawsuits, will only accelerate the trends making California unaffordable.

Climate change is back in court in California, and an influential legal expert just gave away the game with surprising candor. Speaking on a panel in early October, environmental lawyer and climate plaintiff adviser David Bookbinder acknowledged that climate lawsuits are designed to raise costs for consumers: “You sue an oil company, an oil company is liable, the oil company then passes that liability on to the people who are buying its products.” The end game, he explained, is “to achieve the goals of a carbon tax.”

We are now witnessing this strategy in action.

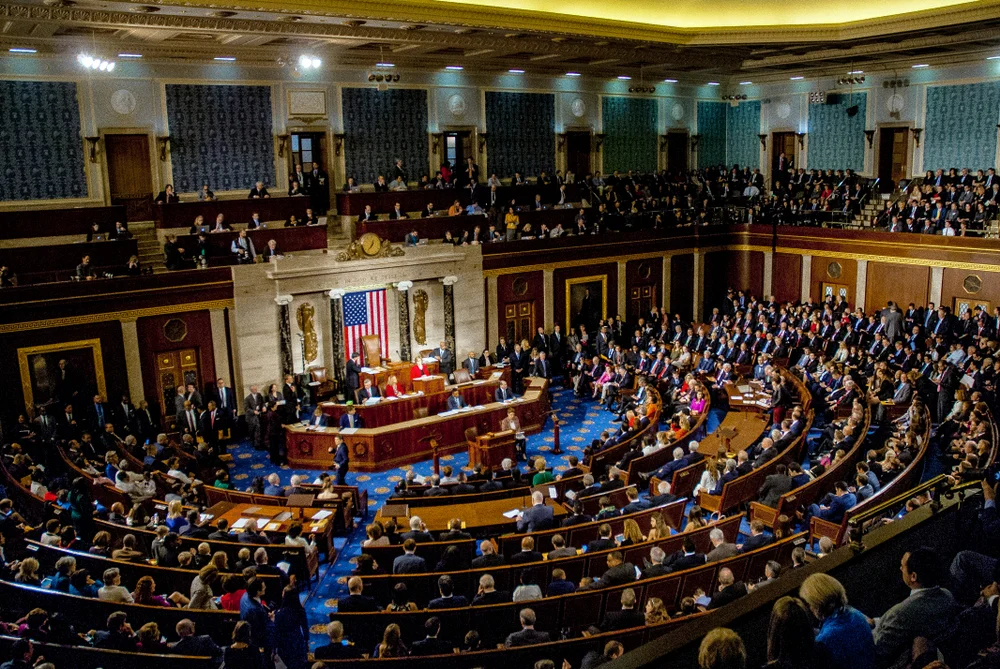

This Friday, San Francisco Superior Court Judge Ethan Schulman will hear arguments to stop public officials and government-retained private attorneys from imposing a carbon tax on Californians through the guise of a lawsuit. Initiated by the state and eight of its municipalities against energy companies, the lawsuit blames them for contributing to climate change, seeking “equitable relief, penalties, and damages.”

For Californians, this is a familiar problem. California’s political establishment loyally caters to leftwing interest group priorities, whatever their effects on affordability. Gas prices in California are $1.60 above the national average, and its electricity prices have risen faster than any other state over the past six years, due in no small part to the state’s ambitious greenhouse gas mandates and costly rooftop solar incentives.

Public officials who truly care about their people would avoid dialing up already sky-high energy prices. However, in California, affordability always loses to climate concerns. The state legislature has mandated that all retail electricity in California must come from carbon neutral sources by 2045. A 2025 Pacific Research Institute study estimates that the average household will pay an extra $700-$800 per year to meet the mandate. That is $17,000 to $20,000 in surplus expenses over a 20-year period for the privilege of living and working in California.

The perennial problem for climate activists is how to save the village without causing all the people to move to Dallas, Phoenix, or somewhere else they can afford to raise a family. A backdoor climate tax, the ultimate aim of the climate lawsuits, will only accelerate the trends making California unaffordable. The pushback from lower- and middle-income Californians, who are tired of being squeezed by the state’s high cost of living, makes a judicially-imposed tax even more attractive for California politicians who do not want to offend climate elites by opposing their latest regressive idea in public. According to economists Corbett Grainger and Charles Kolstad of the University of Wisconsin and Stanford, respectively, the carbon tax burden “is much higher among lower income groups than higher income groups.”

Not to mention, the lawsuit is flawed. The state gets only four years (three for cities) to sue after discovering the grounds for a case. The public has known about climate change for decades. California has been an active participant in climate change litigation since at least 2003. The clock has run out, and the case should be dismissed for that reason.

To try to circumvent this issue, the state and cities say that they have only recently become aware of the views that oil and gas companies have been expressing on climate change. That’s hard to believe because the energy companies’ views (including their opposition to international climate agreements) have been covered in the front pages of major news publications like the New York Times since the 1990s.

Apart from being way too late, the lawsuit has a more fundamental problem. The climate plaintiffs are looking to the courts to regulate consumer choice in the oil and gas sector. But judges are appointed to apply the law, not create it anew for products consumed by millions of Californians every day. The law on the books that regulates interstate carbon emissions is the federal Clean Air Act, not state law, and a “growing chorus” of judges, to quote a recent opinion, have dismissed cases nearly identical to California’s for this reason.

One entity stands to benefit significantly if California’s climate lawfare continues — the politically connected, San Francisco-based law firm Sher Edling LLP, which the municipalities have signed up to represent them. The firm donates to the campaign arm of Democratic state attorneys general (almost $50,000 from 2023 to 2024) and collects money (over $3 million from 2022 to 2023) from progressive sources tied to the Democratic party such as the nonprofits New Venture Fund and the Tides Foundation. While the firm’s agreements with the municipal plaintiffs are not public, some of Sher Edling’s climate contracts recovered through freedom of information laws indicate a substantial payday for them: 16.67 percent of the first $150 million in recoveries, and 7.5 percent of all additional damages.

Judge Schulman should dismiss the climate claims as outside the reach of California law. Californians should object because they reflect the state’s most dysfunctional tendencies.

Michael Toth is the Director of Research at the Civitas Institute at the University of Texas at Austin.

Constitutionalism

Amicus Brief: Hon. William P. Barr and Hon. Michael B. Mukasey in Support of Petitioners

Former AGs Barr and Mukasey Cite Civitas in a SCOTUS Brief

Rational Judicial Review: Constitutions as Power-sharing Agreements, Secession, and the Problem of Dred Scott

Judicial review and originalism serve as valuable commitment mechanisms to enforce future compliance with a political bargain.

Supreme Court showdown exposes shaky case against birthright citizenship

Supreme Court will hear challenges to Trump's order ending birthright citizenship, testing the 14th Amendment's guarantee for babies born in America.

Trump’s Tariff Tantrum

Trump leaps from the frying pan into the fire in the aftermath of Learning Resources v. Trump.

The Administrative State’s Sludge

Congress has delegated so much power across so many statutes that it’s hard to find a question of any public importance to which some agency cannot point to policymaking authority.

.avif)

.avif)

.webp)