The Myth of Milliken

Adams’ misplaced search for a past “silver bullet” of educational egalitarianism reminds us how hard real progress is — especially as today’s achievement gap widens again.

The Supreme Court’s 1974 decision in Milliken v. Bradley ranks among the Court’s most important school desegregation rulings. It brought judicial efforts to achieve racial integration through cross-district, urban-suburban busing in the North to a halt. To some who still remember that fateful decision, it represents a prudent movement back toward the original color-blind interpretation of Brown v. Board of Education. To many civil rights advocates and law professors, in contrast, it marked a betrayal of what Justice Steven Breyer has called “the hope and promise of Brown,” a cynical Nixonian bid to woo white voters by keeping Black students out of suburban schools. To them, Milliken v. Bradley ranks with Plessey v. Ferguson as one of the Court’s most vile decisions.

University of Michigan law professor Michelle Adams falls into the latter camp. A native Detroiter, she provides an extremely detailed — nearly 500-page — history of education politics and litigation in Detroit from the mid-1960s through the late 1970s. For her, it is a bitter and personal story: the inter-district busing ordered by the lower court was “our last, best hope to desegregate our schools and our neighborhoods.” She asserts — without assembling much evidence — that such court-ordered integration was the best way to provide minority students with the “equal educational opportunity” briefly mentioned by Chief Justice Warren in his Brown decision.

The good news is that Adams’ prose is more that of a journalist than a law professor. She has surveyed a remarkable array of sources, including newspaper articles, legal transcripts, and personal interviews. Her effort to integrate the legal, political, and educational features of the story is commendable. The bad news is that she never offers an analytical framework to pull all these diverse pieces together. We read so many descriptions of individual trees that the contours of the forest elude us. Just as importantly, many of the elements she recounts do not support the larger story she claims to tell.

Adams makes it very clear that for her, Brown required the type of urban-suburban busing stymied by the Court’s Milliken decisions. She makes this plain in her opening pages:

Because of Brown, students had a right not to be confined to racially segregated schools. Due to Milliken, however, for most black students in the North, the rights protected under Brown were meaningless. Brown had been violated. . . . Milliken signaled that this country’s serious effort at school integration had come to an end. . . . [Milliken] suggested that the default position was actually much closer to ‘separate but equal.’ (xxii)

This is a common reading of Brown, but far from an obvious or uncontested one. In fact, the claim that Brown required a court-ordered end to what became known as “racial isolation” and “racial containment” and the achievement of racially balanced schools had never been established by the Court in the years before or after Milliken. The first explicit defense of this position did not appear in a Court opinion until Justice Breyer’s 2007 dissent in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle.

As I have shown in The Crucible of Desegregation: The Uncertain Search for Educational Equality, for decades after 1968, the Supreme Court oscillated between two very different understandings of Brown. According to the “color-blind/limited intervention” understanding, the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits public schools from using race to assign students to schools or from treating them differently at any stage of education. Race-based remedies can only be used to cure proven intentional discrimination. Otherwise, courts should defer to the judgment of state and local education officials. This is the position Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP had adopted in the original desegregation litigation.

By the late 1960s, a second understanding had begun to emerge, challenging this commonly accepted interpretation. According to this “equal educational opportunity/racial isolation” view, Brown required courts to take much more extensive action to assure that all children — not just Black students — receive equal educational opportunity. It mandates school districts to eliminate what at the time was called “racial isolation” and Adams calls “racial containment,” that is, schools that are predominantly or identifiably Black. The unstated assumption is that educational equality requires minority students to attend schools that are majority white. If this requires federal courts to override municipal boundaries and order extensive busing between urban centers and suburban peripheries, so be it.

The Supreme Court inched toward the latter interpretation between 1968 and 1973, moved back toward the color-blind approach between 1974 and 1977, swerved back in 1978-1980, and then abandoned the field for over a decade. Not until recent years has it fully endorsed the color-blind interpretation. The ambiguity of Chief Justice Warren’s short opinion in Brown provided some support for each understanding. The racial isolation/containment view rests more on a contested reading of social science evidence than on constitutional interpretation. Adams’ insistence that Milliken was a betrayal of Brown requires an argument, not just an assertion — something the reader will not find in this very long book.

Adams' insistence that Brown requires suburban/urban busing to achieve racial balance was not the position of NAACP lawyers throughout the Milliken litigation. Their goal was the even distribution of white and Black students within Detroit's boundaries. Lawyers representing white parents within Detroit pushed the inter-district busing remedy to bring more high-income white students into the schools their children would attend.

Adams accurately reports the NAACP’s position, but fails to acknowledge the difficulty it creates for her larger argument. NAACP lawyers focused exclusively on Detroit alone, opposing efforts to bring the suburbs into the case. Paul Dimond, a member of the NAACP litigation team on whom Adams frequently relies (and the author of an excellent book on the subject), explained that the suburbs “need not be made parties if they are not necessary for providing relief.” “As to appropriate remedies, neither [chief litigator Nathaniel] Jones nor the NAACP had a clear idea at the outset.” Even after Judge Roth had found the Detroit school system unconstitutionally segregated, “we continued to avoid taking any position on metropolitan relief.”

The NAACP insisted that a Detroit-only plan that spread the remaining white students evenly throughout the school system would cure the constitutional violation and improve the quality of education in the city. When faced with the question of what good “racial balancing of all the schools” would do if it will just result “in a system with predominantly black schools,” Dimond responded, “there is nothing wrong with majority-black or all black schools per se; to be black is not to be inherently inferior, as the question seemed to assume.” But, of course, the assumption that predominantly Black schools are inherently inferior was the central, if awkward, assumption of Adams’ “containment” theory.

Adams also describes well the divisions among Black leaders and voters within Detroit. The litigation arose from a debate within the city about how to improve the quality of education it offered its children. One alternative, the one initially favored by city leaders — including, most importantly, then-State Senator and later Mayor Coleman Young — was decentralization. The goal was to give Black voters more control over schools in an increasingly Black city. The other alternative, most forcefully advocated by the white school board chairman, Abraham Zwerdling, was integration, which in effect meant spreading the declining number of white students more evenly throughout the system. This was not an even political fight: Zwerdling soon lost his seat; Young served as mayor for twenty years. Adams notes that support for busing was soft among Black voters.

Support for urban/suburban busing came almost entirely from Judge Steven Roth, egged on by the white Detroiters who had been allowed to intervene in the case. As Adams and many others point out, Roth underwent a conversion in the 41-day trial. Originally skeptical of the NAACP’s constitutional arguments, he became convinced that government actors had engaged in housing segregation that led to segregated schools.

Adams effectively reviews the housing evidence that had a profound impact on the judge. She says far less about the evidence that convinced him that using busing to eliminate predominantly Black schools would improve the educational opportunities of minority students. The evidence on housing was central to Roth’s relatively uncontroversial liability finding. The evidence on education was crucial to the extraordinary remedy he fashioned after finding a constitutional violation.

Judge Roth later told a reporter, “We all got an education during the course of the trial. It opened my eyes.” How good was the evidence provided by the plaintiff’s expert witnesses? Throughout her lengthy discussion of the trial, Adams assumes that those witnesses were utterly reliable. She ignores the fact that the parties with the greatest interest in challenging their assertions—the suburbs—were not allowed to intervene. To a large extent, the litigation was collusive; the Detroit school board generally agreed with the plaintiffs’ witnesses. Roth did not allow social scientists who disagreed with the NAACP’s witnesses — such as Harvard’s David Armour — to testify.

One of the most significant gaps in Adams’ book is her failure to address the detailed critique of the evidence presented by Eleanor Wolf in Trial and Error: The Detroit School Segregation Case (1981). This is one of only two book-length examinations of the case, and by far the most extensive review of the expert testimony. Yet it does not appear even once in the text of Adams’ book or in her 80 pages of footnotes.

According to Wolf,

Taken as a whole, the message of the testimony on education was that school resources could not be equalized, learning could not be effective, background disadvantages could not be overcome in the absence of racial (plaintiffs’ emphasis) or race-class (defendants’ emphasis) mixture in the classroom. Mandatory reassignment to create such a mixture would improve the academic achievement of blacks, would not harm (and probably would help) whites, would stimulate black aspirations, enhance black self-esteem, heighten teachers’ expectations, and improve interracial relations in both schools and society.

Wolf argues that these contentions were based on badly flawed social science evidence, and that the structure of the trial prevented Judge Roth from adequately understanding the educational issues. Adams no doubt disagrees with Wolf’s assessment. But her failure to address Wolf’s arguments — or the claims of many other critics of busing — is shocking. Her review of the evidence on the educational benefits of extensive busing to reduce isolation is limited to a few pages in the penultimate chapter.

Can we say for certain that if Milliken had come out differently — if the Court had authorized urban/suburban busing throughout the North and West — that the education offered to minority students would not have improved? No. Not only is it hard to prove a negative, but the long-term consequences would depend at least in part on how that effort was carried out and the response of white parents in the suburbs. We do know that in the one northern city in which inter-district busing was mandated, Wilmington, Delaware, the results were neither wonderful nor catastrophic. As in most parts of the country, the racial achievement gap narrowed but hardly disappeared.

Wilmington points to another part of the story that Adams tends to gloss over. The young, liberal Democratic Senator from Delaware at the time was Joseph Biden. Over the course of the decade, Biden became an outspoken critic of busing — a fact Kamala Harris highlighted in her brief run for president in 2020. Adams notes that in 1972, the winner of the Democratic primary in Michigan — one of the most liberal states in the nation at the time — was the racist George Wallace. The busing issue was tearing the Democratic Party apart. It is likely that if the Court had ruled differently in Milliken, Congress would have sent an anti-busing constitutional amendment to the states, and the requisite number of states would have approved it. In presenting opposition to busing as a cynical ploy of the Nixon administration, Adams never comes to terms with its deep unpopularity.

Adams’ story has an air of nostalgia, a look back at a time when the solution to educational inequality seemed simple and within our grasp. In retrospect, though, that silver bullet was neither simple nor graspable. Since the 1990s, we have searched for less grand reforms that can both garner political support and improve schooling for minority students. Some worked, some failed. For the first decade and a half of the twenty first century, we made modest progress in reducing the racial achievement gap. More recently, it has widened. We should not allow nostalgia and wishful thinking to distract us from the arduous task before us.

R. Shep Melnick is the Thomas P. O'Neill, Jr. Professor of American Politics at Boston College, and author of The Crucible of Desegregation: The Uncertain Search for Educational Equality (Chicago, 2023).

Constitutionalism

Amicus Brief: Hon. William P. Barr and Hon. Michael B. Mukasey in Support of Petitioners

Former AGs Barr and Mukasey Cite Civitas in a SCOTUS Brief

Rational Judicial Review: Constitutions as Power-sharing Agreements, Secession, and the Problem of Dred Scott

Judicial review and originalism serve as valuable commitment mechanisms to enforce future compliance with a political bargain.

State Courts Can’t Run Foreign Policy

Suncor is also a golden opportunity for the justices to stop local officials from interfering with an industry critical to foreign and national-security policy.

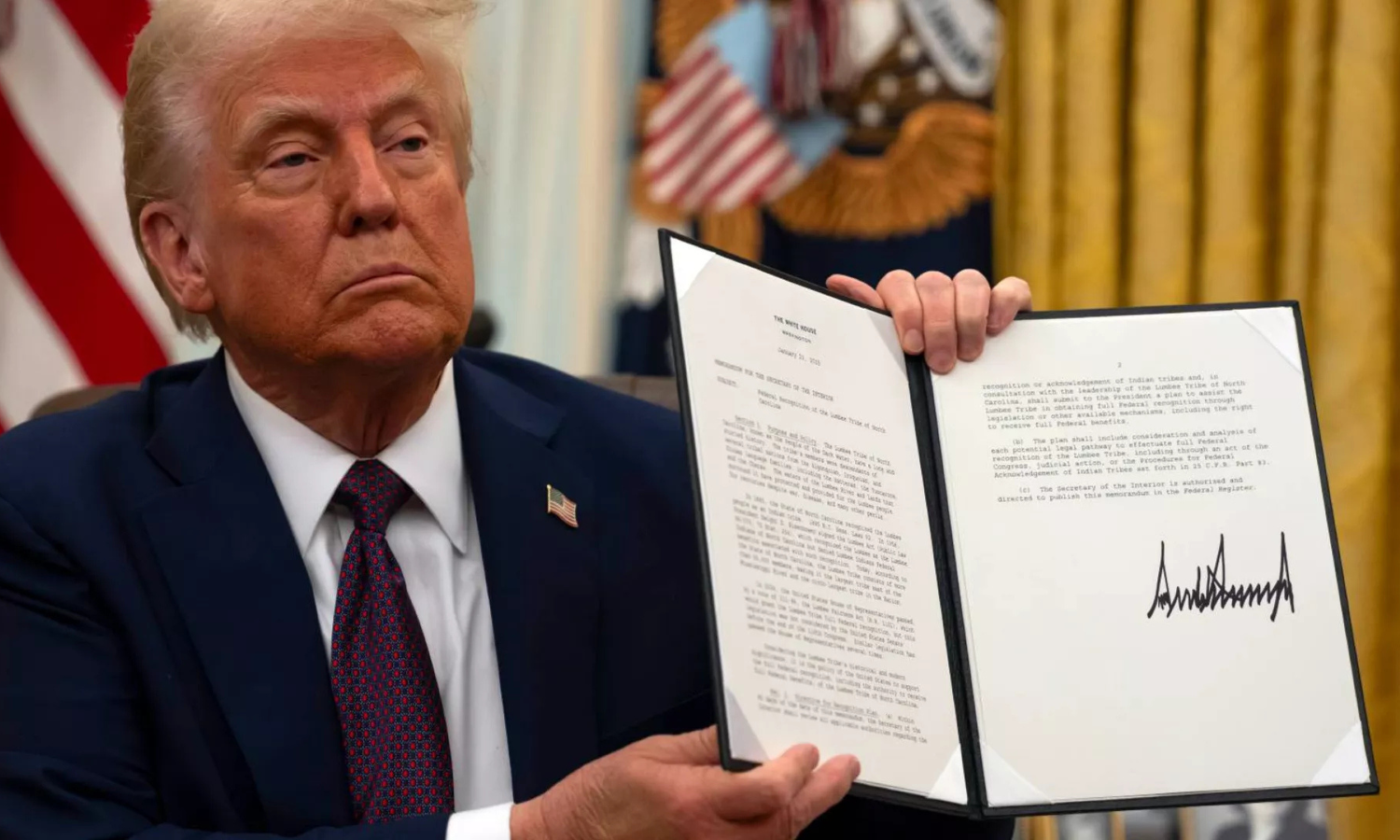

Supreme Court tariff ruling should end complaints that justices favor Trump

John Yoo writes on the Supreme Court’s decision on President Trump’s tariff case.

Trump’s Tariff Tantrum

Trump leaps from the frying pan into the fire in the aftermath of Learning Resources v. Trump.

The Administrative State’s Sludge

Congress has delegated so much power across so many statutes that it’s hard to find a question of any public importance to which some agency cannot point to policymaking authority.

.avif)

.webp)