Just Follow the Law

Be nervous whenever anyone says “just follow the law,” because although that principle is true, it is also true that “[e]verything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

A phrase, often (mis)attributed to Albert Einstein, goes something like this: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” Unfortunately, public discourse all too often skips nuance. The recent back-and-forth over whether members of the military should refuse to obey unlawful orders falls within this category. Of course, they should follow the law. Everyone should. By definition, no one can lawfully disobey the law. The problem, though, is that it can be difficult to know what the law requires, even for legal experts. This problem is not limited to the military context; it is found to some degree throughout the entire system. And the law’s tools to mitigate this problem may sometimes fall victim to the very problem they are intended to minimize — uncertainty.

My point is not to discuss the military but rather to explain that deeper problem. At the outset, I want to emphasize that, in many cases, it is not particularly difficult to determine what the law requires. Unfortunately, though, that is not always true.

Scholars of jurisprudence debate what law is and what is and is not “unlawful.” Although there are arguments for (and against) many conceptions, one well-known practical answer comes from Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who explained:

The reason why [law] is a profession, why people will pay lawyers to argue for them or to advise them, is that in societies like ours the command of the public force is intrusted to the judges in certain cases, and the whole power of the state will be put forth, if necessary, to carry out their judgments and decrees. People want to know under what circumstances and how far they will run the risk of coming against what is so much stronger than themselves, and hence it becomes a business to find out when this danger is to be feared. The object of our study, then, is prediction, the prediction of the incidence of the public force through the instrumentality of the courts.

To be sure, Holmes’s view cannot be complete. It suggests, for example, that if one knows for whatever reason that no court or similar body will punish an action, that action is lawful. But that surely is not so. If someone living on a remote island knows that he has only six months to live and that it is impossible for the marshal to make it to the island within six months to make an arrest, one can predict that no governmental punishment will be forthcoming if that person were to do all manner of ill doings to his fellow islanders. But surely no one thinks those ill doings would be lawful. Thus, law cannot just be about predicting punishment.

Even so, the prediction model at least has some value. Often, people are wholly committed to doing what the law requires, if only someone would tell them what that is. Simply reading the law, however, does not always answer the question. For example, some laws are so complicated that no ordinary person could understand them without assistance. (Try figuring out the law governing the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.) Also, sometimes, sitting down and reading the law doesn’t help much because the terms are open-ended. For example, what is a “reasonable” search? Or what does “due process” require? Furthermore, sometimes what looks like a “law” (for example, a statute) actually isn’t a law because a higher authority — such as the Constitution — supersedes it. If a lawyer can consistently predict how a court will resolve such issues, ordinary people quite naturally will turn to lawyers for help. At least descriptively, then, Holmes’s account of why law is a profession that ordinary people pay money for is hard to brush aside.

Unfortunately, lawyers don’t always know what courts will do, either. To be sure, even for difficult legal questions, lawyers generally can predict the range of possible outcomes better than someone without legal training. But quite often, even the best lawyers in the world cannot know precisely what a court will decide, and so can only advise a client that a certain path is unlikely to be found unlawful. Indeed, the lawyer who could predict with perfect accuracy what courts will do could make a fortune on Wall Street, because court decisions change markets.

What should someone who wants to follow the law do when no one knows what a court will say the law requires until after the court issues its decision?

One solution is to avoid even coming close to the line. If option one is definitely unlawful, option two is definitely lawful, and option three is uncertain, one way to avoid violating the law is to do option one. But that is not always possible. The tort of negligence, for example, asks what a “reasonable” person would do. Would a reasonable person, however, warn against every unlikely, speculative danger, even if it means adding pages of boilerplate warnings to a product that cause customers’ eyes to glaze over? Or would a reasonable person focus on warning about the most likely dangers, even if doing so means some customers with highly idiosyncratic characteristics may not know about a potential risk? Even with excellent legal counsel, that can be a difficult question. Alas, “[c]ase law concerning the adequacy of warnings and instructions is not particularly illuminating.”

Nor is avoiding any chance of acting unlawfully always even desirable; certain types of beneficial conduct sometimes require not running away from the lawful/unlawful line. For example, a newspaper could avoid defamation by saying nothing, or a police officer could avoid unlawful arrests by arresting no one. But that would mean that there would be no news for anyone to read — if they even had time to read while dodging dangerous criminals.

The law seeks to account for the reality that legal obligations can sometimes be unclear. As to defamation, for example, the Supreme Court has held that “actual malice” is sometimes required, beyond mere falsity. In other words, even if a publisher says something untrue about, say, a prominent politician, the newspaper (generally) cannot be held liable for that error unless that error effectively was a deliberate falsehood or something like it. To avoid “chilling” publishers from speaking, the Court concluded in New York Times v. Sullivan that publishers need “breathing space” to make reasonable mistakes.

Other examples abound. For example, the venerable rule of lenity (generally) requires courts to interpret ambiguous criminal statutes in favor of the defendant. The Supreme Court has recognized a similar “fair warning” principle with respect to administrative agencies; agencies (generally) cannot impose liability without providing regulated entities with fair warning about how the agency interprets its authority and what is unlawful. And the void-for-vagueness doctrine (generally) bars enforcement of laws that fail to give ordinary people fair notice of what conduct is prohibited or invite arbitrary enforcement.

The same type of reasoning sometimes applies to governmental officials. For example, in Heien v. North Carolina, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Fourth Amendment’s “reasonable suspicion” standard permits police to make traffic stops based on reasonable mistakes so long as the officer’s view was objectively reasonable. Thus, the Court concluded that an officer did not violate the Fourth Amendment by stopping a motorist whose vehicle had only one functioning brake light. After all, the Court reasoned, it was a reasonable mistake to believe that North Carolina required two working brake lights. In reaching its conclusion, the Court emphasized that even Chief Justice John Marshall—who famously said in Marbury v. Madison that “[t]he very essence of civil liberty certainly consists in the right of every individual to claim the protection of the laws, whenever he receives an injury”—recognized the concept of reasonable mistakes of law. “A doubt as to the true construction of the law is as reasonable a cause for seizure as a doubt respecting the fact.”

Similar analysis underlies qualified immunity. Under this doctrine, government officials (generally) are not subject to civil liability under federal law unless they violate a clearly established federal right. A right is “clearly established” when existing precedent would make it obvious to any reasonable official that the conduct was unlawful, or where the violation is so obvious that there is no need for a court to have said something before. The doctrine aims to balance two interests: allowing damages actions to deter official misconduct while protecting officials from litigation arising from reasonable mistakes made in the course of their duties. As the Court explained, “a policeman’s lot is not so unhappy that he must choose between being charged with dereliction of duty if he does not arrest when he had probable cause, and being mulcted in damages if he does.”

Such doctrines are controversial because they create “breathing space” for beneficial activities at the expense of more vigorous enforcement of the law. In other words, there are tradeoffs.

One problem, though, is that even if these tools to mitigate the law’s lack of clarity worked perfectly (and they don’t, unfortunately; judges regularly disagree), there often are questions about their own lawfulness. As Justice Scalia explained, for example, about doctrines like the rule of lenity, “whether these dice-loading rules are bad or good, there is also the question of where the courts get the authority to impose them. Can we really just decree that we will interpret the laws that Congress passes to mean less or more than what they fairly say?” Whether New York v. Sullivan comports with the Constitution, moreover, is debated. And scholars have challenged qualified immunity’s lawfulness with arguments that I believe are mistaken, but that are not frivolous by any means.

Again, none of this is to say that anyone should ignore the law; often, the law is clear (or at least clear enough), and even when it is not, the law’s own tools provide a workable answer. But be nervous whenever anyone says “just follow the law,” because although that principle is true, it is also true that “[e]verything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

Aaron L. Nielson holds the Charles I. Francis Professorship in Law at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law. Before joining the faculty, Professor Nielson served as Solicitor General of Texas where he argued five cases in the U.S. Supreme Court and oversaw all appellate litigation for the State of Texas.

Constitutionalism

Amicus Brief: Hon. William P. Barr and Hon. Michael B. Mukasey in Support of Petitioners

Former AGs Barr and Mukasey Cite Civitas in a SCOTUS Brief

Rational Judicial Review: Constitutions as Power-sharing Agreements, Secession, and the Problem of Dred Scott

Judicial review and originalism serve as valuable commitment mechanisms to enforce future compliance with a political bargain.

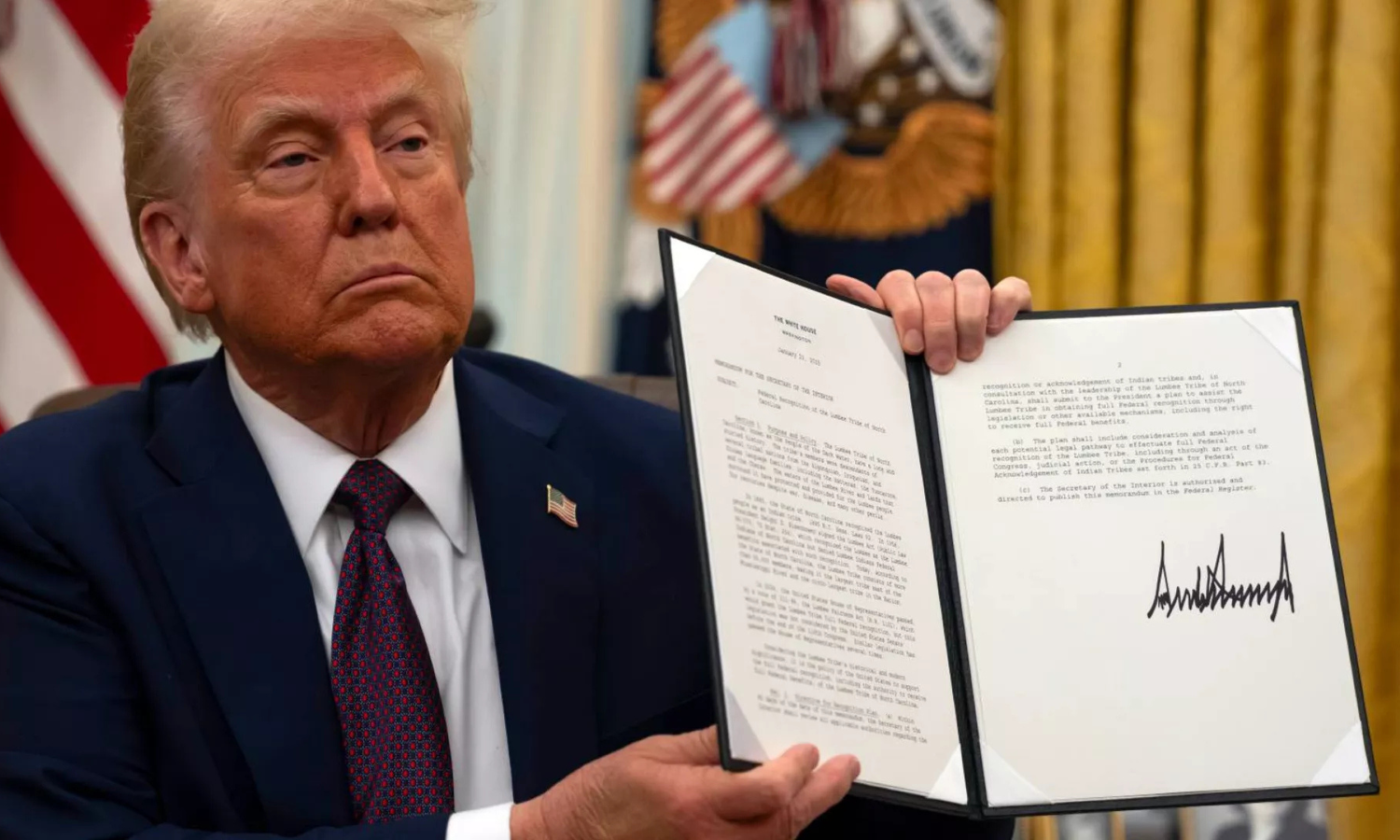

Supreme Court showdown exposes shaky case against birthright citizenship

Supreme Court will hear challenges to Trump's order ending birthright citizenship, testing the 14th Amendment's guarantee for babies born in America.

.avif)

.avif)