One Nation Spaced Out

Those making drug policy decisions will make fewer mistakes and less socially damaging ones if they pay attention to what Kevin Sabet wrote in One Nation.

Kevin Sabet’s new book — One Nation Under the Influence — addresses a problem that has bedeviled us for thousands of years: What should individuals and society do about the use of psychoactive substances? Alcohol, of course, is perhaps the oldest and best-known euphoric, and it has been widely used ever since Noah planted his first vineyard. But alcohol is so 20 minutes ago as far as troublesome psychoactive consumables go today. Sabet recognizes that, when discussing the broader issue of drug dependence, regardless of the substance. Unlike Sabet’s first two books — Reefer Sanity: Seven Great Myths About Marijuana and Smokescreen: What the Marijuana Industry Doesn’t Want You to Know — One Nation does not focus on a specific category of illicit drugs. No, his recent book is far more ambitious. While it devotes the bulk of its attention to the problems raised by the principal drugs of concern today such as opioids, particularly fentanyl, One Nation exhaustively considers the entire range of issues that illicit drug use pose. As Sabet put it, he wanted to offer “a dispassionate and in-depth examination of the crisis,” along with proposals for sensible responses that avoid the historical extremes of strict versus lax enforcement, which are often presented as solutions. In so doing, he focuses on the downside of what drug innovation has enabled us to do, how we have used the products of science to do immense harm to ourselves, and what we should do to right the ship.

We face a difficult set of issues here. Should we continue to use a largely criminal-justice-oriented model to deter drug use in the face of continued use? Can that system halt or limit the use of dangerous drugs at a reasonable cost to the individuals caught in its maw and society as a whole, or is illicit drug use inevitable? If the latter, how should we treat people who nonetheless use? Should we step up our efforts to dissuade or deter people from taking up illicit drug use? Should we approach the problem, particularly when use becomes an addiction, not as a moral failing or a violation of each individual’s social obligation to remain clean and sober, but as a disease that should be left to the nation’s medical apparatus? Should we permit adults to use any and all drugs without restriction, leaving each person to make his or her own decision if no one else is injured? How do we prevent experimental drug use from becoming profligate use, leading to addiction? Should we make users pay the price of their erroneous decisions by refusing to provide them with free emergency medical services, let alone free emergency department treatment, even when their lives are at immediate risk? If we are unwilling to allow users to commit slow-motion (or sometimes, as in the case of fentanyl, instantaneous) suicide, should we take up a position somewhere short of legalization by, for example, limiting drug use to adults and banning the use of some drugs without exception (and, if so, which ones)?

Sabet is well qualified to offer us advice. Educated at Oxford University in the U.K., he learned the ins and outs of America’s drug issues working for Democratic and Republican Administrations at the U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy. Since then, he has acquired additional schooling in the drug policy street-fights that occur on Capitol Hill and in the states. Sabet clearly understands the pros and cons on both sides of the drug policy debates, and he uses data to support his analyses and recommendations rather than relying on short, hackneyed nostrums that ignore the difficulties we face. His thoughts are definitely worth considering.

In addition to knowledge, training, and “street smarts,” a willingness to learn from ongoing medical and scientific developments is also important to have in today’s drug policy debates. Modern chemistry has enabled us to synthesize, from plants or chemicals, a host of novel psychoactive substances. Some of those drugs should not be blacklisted, given that they have legitimate medical uses, but they are also potentially (or certainly) troublesome and cannot be freely distributed without causing more pain and suffering than society is willing to bear. Opioids might be the best example. They are, hands down, the world’s primo analgesics, but are also quite addictive, with that latter feature leading to the death of more than 800,000 lives and the ruination of many more since 1999. On top of that, the economic costs of addiction are staggering. Nearly ten percent of our health care expenditures “go toward prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of people suffering from addictive diseases,” and the nationwide cost of addiction has been roughly $1.5 trillion. Worsening our predicament is that some other psychoactive substances, like nitazenes, have no legitimate medical use, no safe use even under medical supervision, and no benefit that cannot be obtained from safer drugs. Unfortunately, we cannot disinvent those drugs, so we must figure out how best to deal with them.

Our history reveals that, since the early twentieth century, the states and federal government have predominantly used a “supply side” approach to illicit drug use. To deter people from making improvident choices with some drugs freely available, the federal government and the states have made it a crime to import, synthesize, distribute, and possess some dangerous drugs (e.g., heroin) and to heavily regulate others by authorizing only licensed physicians to prescribe their use, and even then for only limited purposes (e.g., opioids). The criminal justice system has the biggest hammer available — viz., imprisonment, sometimes for life — that society can bring to bear against anyone who crosses the line, and it has been our remedy of choice for more than a century. Statutes such as the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, and the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 are the three most important acts of Congress that focus on illicit drugs (although the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 also plays an important role in this regard).

If we want to try to prevent the birth of new victims, relieve the suffering of those afflicted by drugs, and fix the predicament of the numerous third-party victims of users’ criminal conduct done to obtain money for their next fix or from living in outdoor drug-use encampments, what should we do?

Fortunately, Sabet offers some advice. He includes recommendations for the steps we can and should take to address the misfortunes of those fettered by what the law ironically labels “controlled substances” (ironic because neither the law nor a large part of our citizenry can control their desire to use them).

Some, but not all, of the recommendations in One Nation involve using the criminal justice system. Sabet believes in a “sticks and carrots” approach. Yet, he is hardly an advocate for a “Lock ’em up and throw away the key” solution. He recognizes that exclusive reliance on law enforcement would be a mistake, and he sees both prevention and treatment, emergency and long-term, as currently underutilized components of a legitimate and likely successful response.

Nonetheless, he recognizes the legitimate and valuable role the criminal justice system can play, for example, through drug courts. He points out that the Multistate Adult Drug Court Evaluation and the majority of other studies have found those courts to be effective “in reducing crime and drug use for nearly all subpopulations, even when accounting for client demographics, specific drug use, criminal histories, and mental health.” In short, compulsory treatment can and does work. “[P]eople who are mandated to undergo addiction treatment fare at least as well as those who volunteer” — perhaps because a judge holds in reserve the possibility of incarceration should the user become recalcitrant.

Similarly, Sabet endorses two comparable approaches: the Hawaii Opportunity Probation with Enforcement (HOPE) program begun by then-Hawaii trial court judge Steve Alm, and the 24/7 Sobriety Program begun by then-local prosecutor Larry Long. The two programs treat offenses induced or accompanied by drug use as an opportunity to treat the causal role of drug use in crime. The programs frequently, but randomly, drug test probationers and use initially short (say, 24 hours) confinement in jail for a failing drug test, with penalties that gradually increase if an offender continues to test “hot” (say, 48 hours for a second failed drug test, 72 or 96 hours for a third failure, and so on). Each program rests on three eminently reasonable foundational propositions.

One is that — as Dr. Bob DuPont, a former drug czar and founder of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, once told me — a voluntary drug treatment program works about as well as a voluntary imprisonment program. Some form of coercion is necessary to get a user’s attention and make him or her realize that there are serious consequences for continuing to get high. Another building block is that the certainty of receiving a punishment matters more than the severity of the penalty imposed. Just ask any parent. The threat that, in six months or more, a child might be “grounded for life” carries far less deterrent effect than being grounded for “this weekend.” And the last proposition is that sanctions should start out “small,” but gradually escalate if necessary to halt continued drug use. That prevents someone from thumbing his or her nose at the system because he or she can tough out a brief stint in jail. Those programs have been quite successful in the states where they originated — Hawaii and South Dakota — but have had mixed results elsewhere (though Alm believes HOPE was not properly implemented in other jurisdictions). Nonetheless, Sabet recommends them, and he is right to do so. I have previously endorsed those programs, and I still believe that they should be tried in other jurisdictions.

Not everyone agrees. In fact, almost any resort to the criminal justice system, particularly its reliance on imprisonment, has come under repeated attack over the past four decades by a host of critics, including the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA), an umbrella organization opposed to the criminalization of drug use that is, in Sabet’s words, “the driving force — and financial might — behind most concerted efforts to legalize and normalize illicit drug use throughout the United States.” Those criticisms largely go as follows: Imprisonment is cruel because drug addiction is a disease. Imprisonment is ineffective because the public has not abandoned drug use, nor have users followed their release from incarceration. Imprisonment is inefficient because prisons are costly to operate. Imprisonment is immoral because we cage human beings for using drugs that are little more dangerous than alcohol. Imprisonment is racist, the most loudly voiced criticism today, despite its quite erroneous underpinnings because too many minorities are incarcerated. Instead of following an unsuccessful path, critics maintain, we should consider drug legalization, the position long favored by libertarians since John Stuart Mill wrote On Liberty in 1859.

Critics also endorse various nonpunitive intermediate approaches. Prominent among them is “harm reduction,” which would (for instance) permit operation of so-called supervised “safe use” sites where users may consume their drug of choice in a safe, nonjudgmental environment, that also dispenses clean hypodermics to avoid transferring diseases such as AIDS among users. Legalization would enable, they contend, the sale of pure forms of drugs that today are adulterated with toxic compounds (like laundry detergent, heavy metals, or xylazine, a veterinary sedative colloquially known as “tranq”) or hyperpotent substances (like fentanyl or nitazene). To be sure, critics of our law-enforcement-heavy strategy are right that the police sometimes go overboard. Those critics are also right that legislatures, seeking less to stop drug abuse than to avoid making enemies of frightfully scared parents, have enacted some drug laws authorizing terms of imprisonment that might lead even the ancient Greek legislator Draco to say, “Whoa!” But drug policy critics who bat from the left have overplayed their hand, in four ways: They go too far in trying to avoid needless punishment-induced suffering without recognizing that drug-induced suffering can be its equal or worse, they have abandoned a utilitarian approach that would include consideration of the societal harms caused by drug use, they mistakenly assume that a person addicted to drugs can make a rational choice to continue their use, and they have confused drug purity with drug safety.

The libertarian position is longstanding, but science has made significant advances in understanding the human brain since 1859, and it would be folly not to reconsider its merits in light of the lessons that science has taught us since Mills put pen to paper namely, that drugs, such as heroin or meth, hardwire the brain to believe that only further use can bring the satisfaction (or relief from withdrawal) that those drugs initially offer—might have persuaded people that the Millsian theory ought to be reconsidered in light of twentieth and twenty first century chemistry and neurology, particularly how the new scourge of America, fentanyl, joins the two sciences on a highway to Hades. But I was wrong. No argument, not even Sabet’s, could persuade them.

Sabet savages the notion that we should throw up our hands and surrender to unlimited drug use. He agrees (as do I) that the answer is not to say to users, to borrow from The Inferno, “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” Drug treatment is necessary, Sabet believes, as is the use of life-saving drugs like naloxone, which can bring back from the brink of death people who overdosed on opioids. But he also correctly realizes that the criminal justice system has a legitimate role to play in forcing individuals into some form of responsibility-based program aiming to help them desist from further drug use. In addition, Sabet urges the federal government to maintain its supply-side efforts to reduce the amount of fentanyl, meth, and other dangerous drugs from entering the United States. We might not be able to arrest our way out of our drug problem, but reducing the supply of deadly substances will undoubtedly save lives, the noblest pursuit that we can undertake in the time given us.

Sabet is truly at his best when he uses data, experience, and history to take on the attitude that society should leave drug policy decisions to each person without the fact or fear of criminal punishment for making a personal choice to consume psychoactive substances. There is now proof of what such a strategy will produce, and it is fatal to their argument.

In 2020, Oregon — the first state to decriminalize possession of small amounts of cannabis, the second state to create a medical cannabis-use program, and the third state to blow past the medical cannabis charade and allow cannabis to be used for recreational purposes — went whole hog by making the possession of small amounts of every illicit drug, including methamphetamine, heroin, and fentanyl, punishable only by a small-scale fine that could be forgiven simply by calling the phone number of a drug treatment facility, without any corresponding requirement of applying for or receiving any drug use treatment. Oregon’s 2020 citizen initiative, known as Measure 110, went even further than Portugal did in 2001 when it passed a similar decriminalization law. Portugal’s law required arrested users to appear before a Commission for the Dissuasion of Drug Addiction, which could order compulsory drug treatment. The new Oregon medical model rested on the assumption that people suffering from a substance abuse disorder wanted to “kick the habit” and needed only the opportunity to do so without being convicted of a crime, an outcome that would tattoo them with a scarlet “F” (for felon) for the rest of their lives. According to the argument in favor of Measure 110, medicalizing drug addiction would better serve the interests of those addicts who want to escape from being shackled to a dangerous drug, as well as society, which wants law enforcement to investigate “real criminals” (robbers, burglars, and the like). In the long run, the program would pay for itself, the argument concluded, as people on the fringe of society returned to the center as productive members of the community. Measure 110, therefore, would result in a win-win.

Wrong.

Oregon’s drug decriminalization program was a debacle; there is no softer criticism that can honestly be used to characterize how badly Oregon’s decriminalization effort worked out. In the name of empathy, Measure 110 wound up killing an unknown number of users. If the goal of Oregon’s Measure 110 was to “meet drug users where they are,” as Sabet notes, the state should have labeled its open-air, drug-use “colonies” with overdose fatalities as Boot Hill Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. The lives that Measure 110 did not take were ruined, both the users and nearby innocent residents — adults, adolescents, and children forced to live in neighborhoods abutting outdoor shooting galleries resembling the Inferno’s Seventh Circle of Hell. Sabet does an excellent job of using the data to make that point.

Sabet also correctly faults the critics’ position for not including an important role for efforts to dissuade or deter people from using drugs. Perhaps to avoid condemning people who see illicit drug use as beneficial, some critics will not give deterrence the prominence that it deserves in preventing dependence. That is particularly important in the case of minors. People who have not used drugs, alcohol, or tobacco before age 21, the evidence reveals, are highly unlikely to abuse any of those drugs during their adulthood. There is no good reason that we should applaud drug use — by minors, certainly, but also by adults — given the number of people who cannot use those substances without becoming the worse for their efforts. We have saved millions of lives by deterring tobacco use, in part by stigmatizing that conduct. We need to use the same strategy in the case of drug use.

My criticisms of One Nation are few. No one book can address every subject, and this book does an excellent job of offering an encyclopedic discussion of current drug policy issues and options. But it falls short in comparing the success rates of different types of treatment. Yes, the book does note (or refers to articles discussing) some of the data collected regarding two relatively recent programs designed to address substance abuse: the HOPE and 24/7 Sobriety programs. But there are numerous other types of drug treatment programs, and Sabet does not tell us what success rate they have had. Success, measured by completing a treatment program and remaining clean and sober for five years afterwards (the “gold standard”), rests on a number of factors: age, sex, length of addiction, follow-up treatment available, use of medication-assisted therapies such as methadone or buprenorphine, and others. It would have been helpful to know which particular programs or treatment categories work best.

Regardless, Sabet’s book is a timely addition to an always-growing drug policy literature. Despite a century-plus of attempts to eliminate (or at least reduce to a minimum) the number of lives wasted, a considerable number of people still turn to dangerous drugs for the temporary euphoria they provide, even though they ultimately lead to a far worse life than users hoped to leave behind. In fact, the problem has worsened over the last two decades because the illicit use of fentanyl has generated a ghastly tally of overdose deaths. As Sabet notes, there have been more drug-related fatalities since 2000 (and counting) than the number of fatalities that the nation has suffered in every post-World War II conflict added together. We must lower the number of preventable drug-related deaths.

We will make mistakes along the way. President Donald Trump made one in December 2025 when he ordered U.S. Attorney General Pamela Bondi to complete the administrative process begun during the Biden Administration to reschedule cannabis, for which there is no medical, policy, or legal justification. He, his successors, and other elected officials doubtless will make others. But they will make fewer mistakes, and less socially damaging ones, if they pay attention to what Kevin Sabet wrote in One Nation. The time necessary to read it is more than justified by the lessons to be learned.

Paul J. Larkin is a Senior Legal Fellow in the Meese Institute for the Rule of Law at Advancing American Freedom. I want to thank Doug Carlson, Professor Bertha K. Madras, John G. Malcolm, and Luke Niforatos for helpful comments on an earlier iteration of this essay. Any mistakes are mine.

Pursuit of Happiness

The Rise of Latino America

In The Rise of Latino America, Hernandez & Kotkin argue that Latinos, who are projected to become America’s largest ethnic group, are a dynamic force shaping the nation’s demographic, economic, and cultural future. Far from being a marginalized group defined by oppression, Latinos are integral to America’s story. They drive economic growth, cultural evolution, and workforce vitality. Challenges, however, including poverty, educational disparities, and restrictive policies, threaten their upward mobility. Policymakers who wish to harness Latino potential to ensure national prosperity and resilience should adopt policies that prioritize affordability, safety, and economic opportunity over ideological constraints.

Exodus: Affordability Crisis Sends Americans Packing From Big Cities

The first in a two-part series about the Great Dispersion of Americans across the country.

.jpg)

The False Equivalence of Multicultural Day

Parents have an affirmative obligation to reinforce patriotic values and counter the narratives that are taught in school.

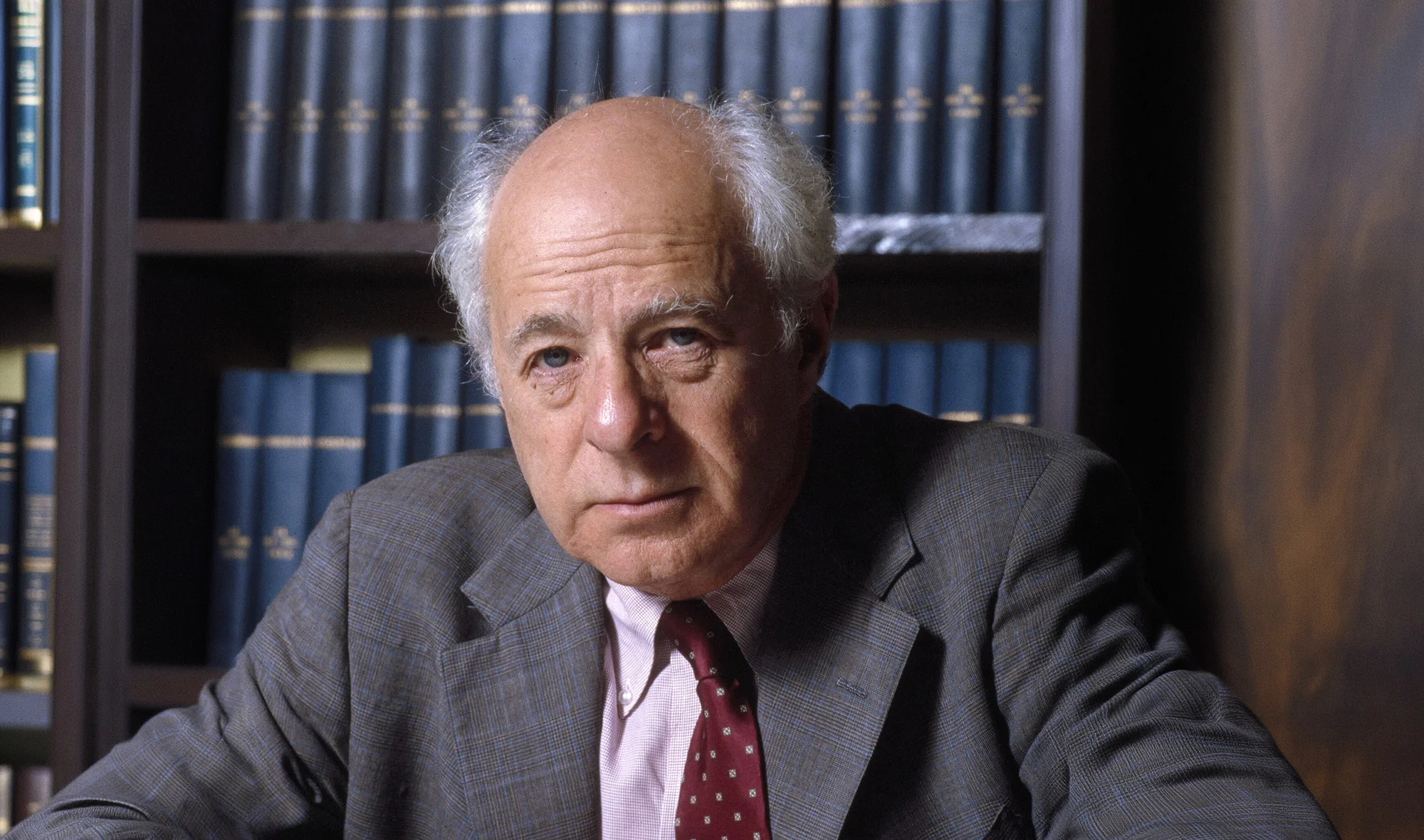

Norman Podhoretz: American Patriot, Faithful Jew, and Indomitable Defender of Civilization

Podhoretz never turned on the promise of America.