The Rise of Latino America

Download the full paper here

Executive Summary

In The Rise of Latino America, we argue that Latinos, who are projected to become America’s largest ethnic group, are a dynamic force shaping the nation’s demographic, economic, and cultural future. Far from being a marginalized group defined by oppression, Latinos are integral to America’s story. They drive economic growth, cultural evolution, and workforce vitality. Challenges, however, including poverty, educational disparities, and restrictive policies, threaten their upward mobility. Policymakers who wish to harness Latino potential to ensure national prosperity and resilience should adopt policies that prioritize affordability, safety, and economic opportunity over ideological constraints.

Important Points:

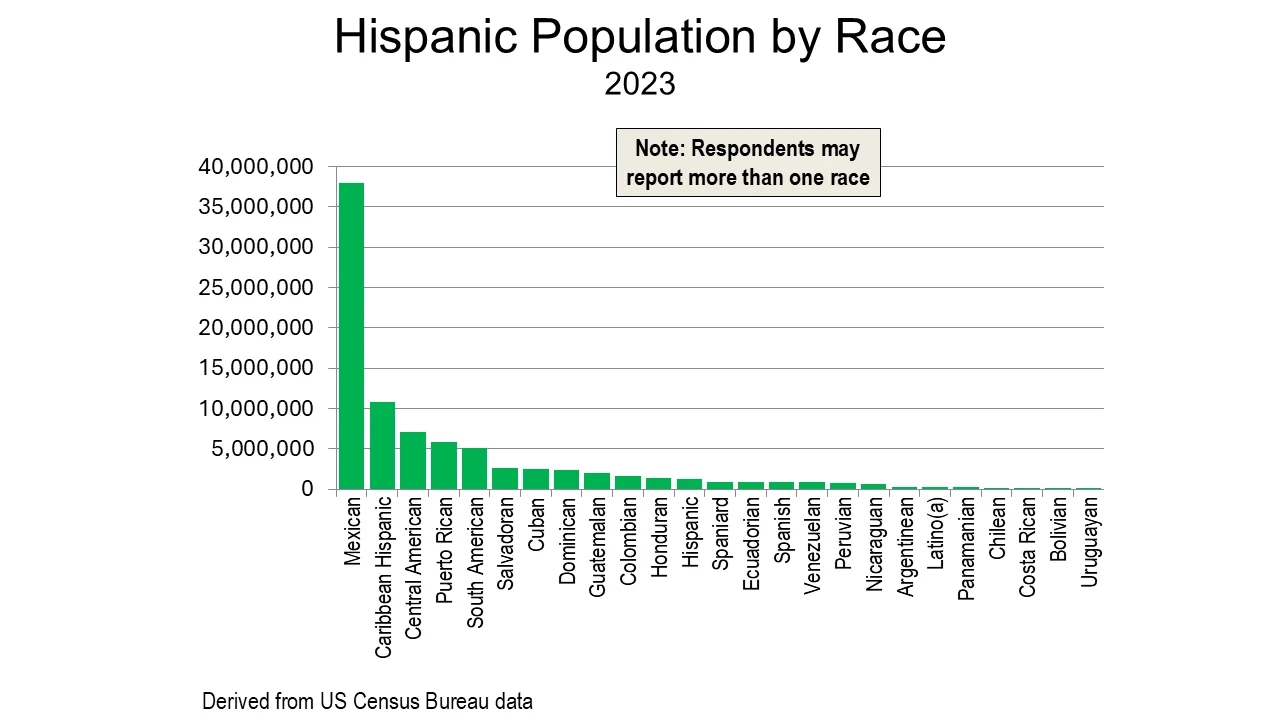

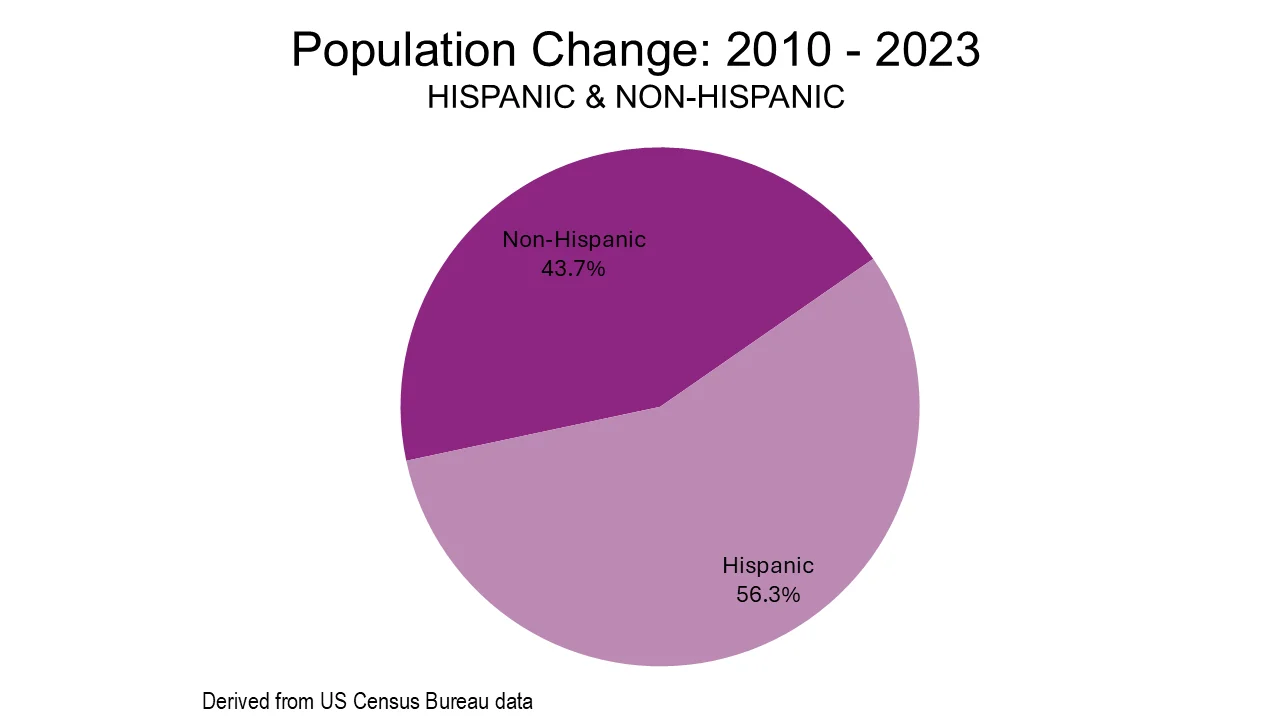

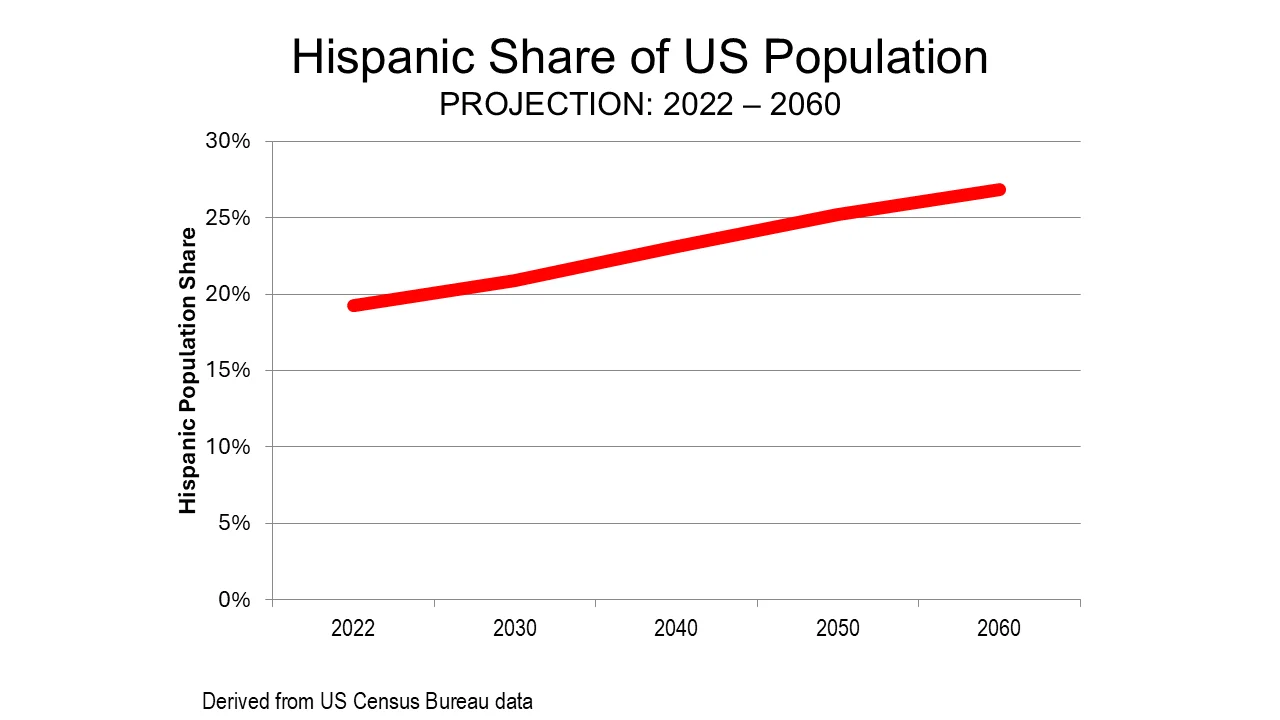

- Demographic Surge: Latinos have grown from 5% of the U.S. population in 1970 to 20% in 2023, accounting for 56.3% of population growth from 2010 to 2023. By 2060, they will drive nearly all net population growth.

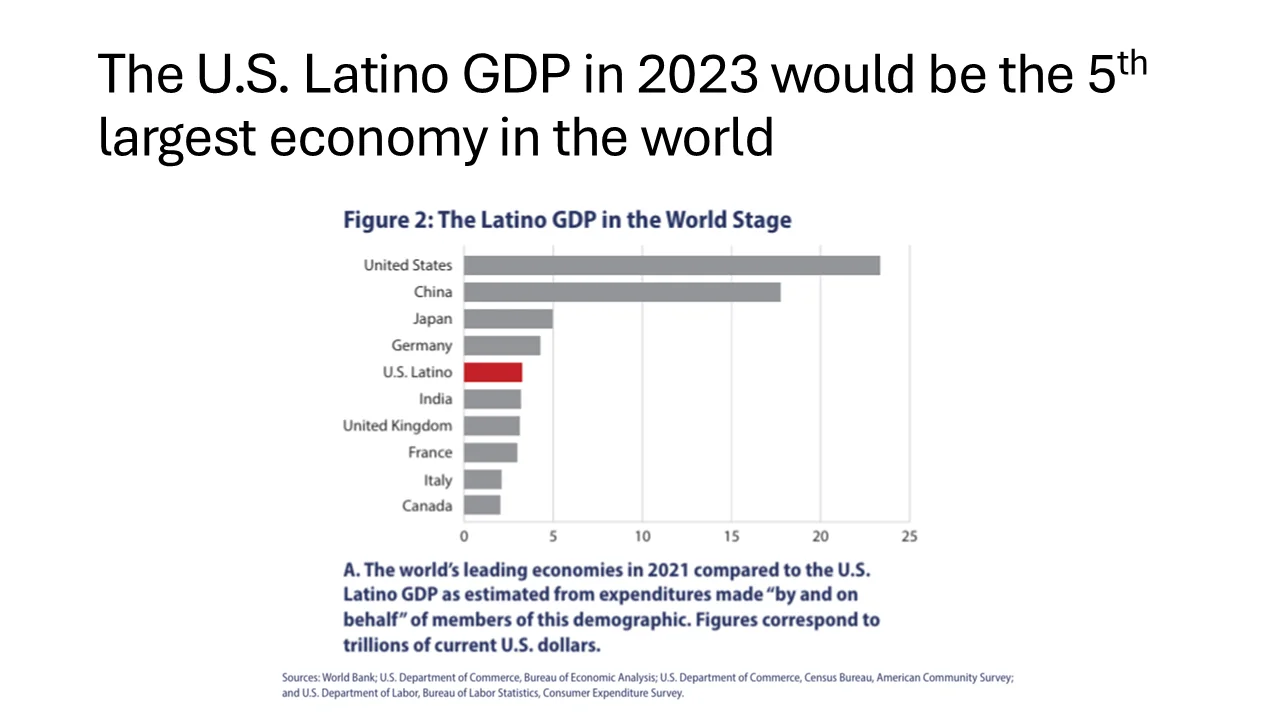

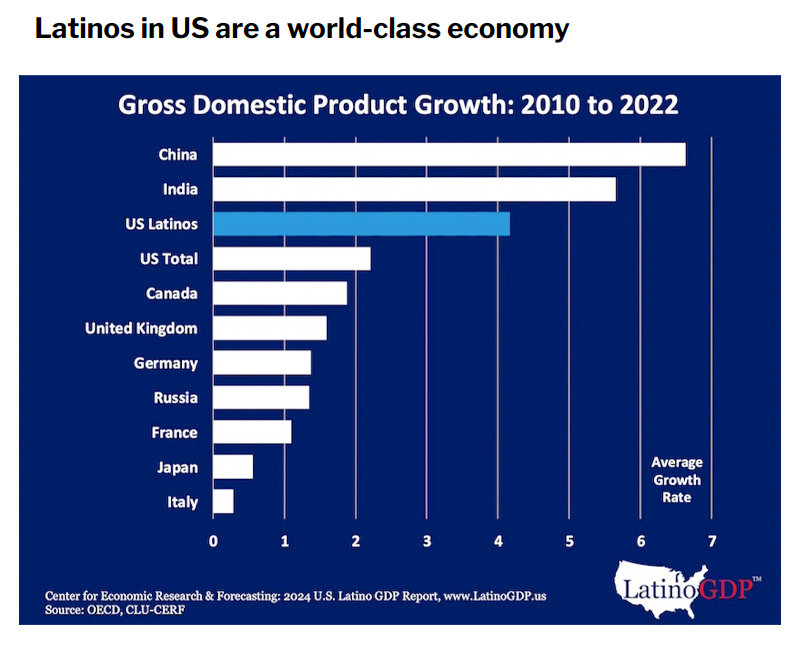

- Economic Powerhouse: The U.S. Latino G.D.P. reached $3.7 trillion in 2022, the world’s fifth-largest, growing at 4.6% annually and outpacing the national average. States like Texas and Florida see significant Latino economic contributions.

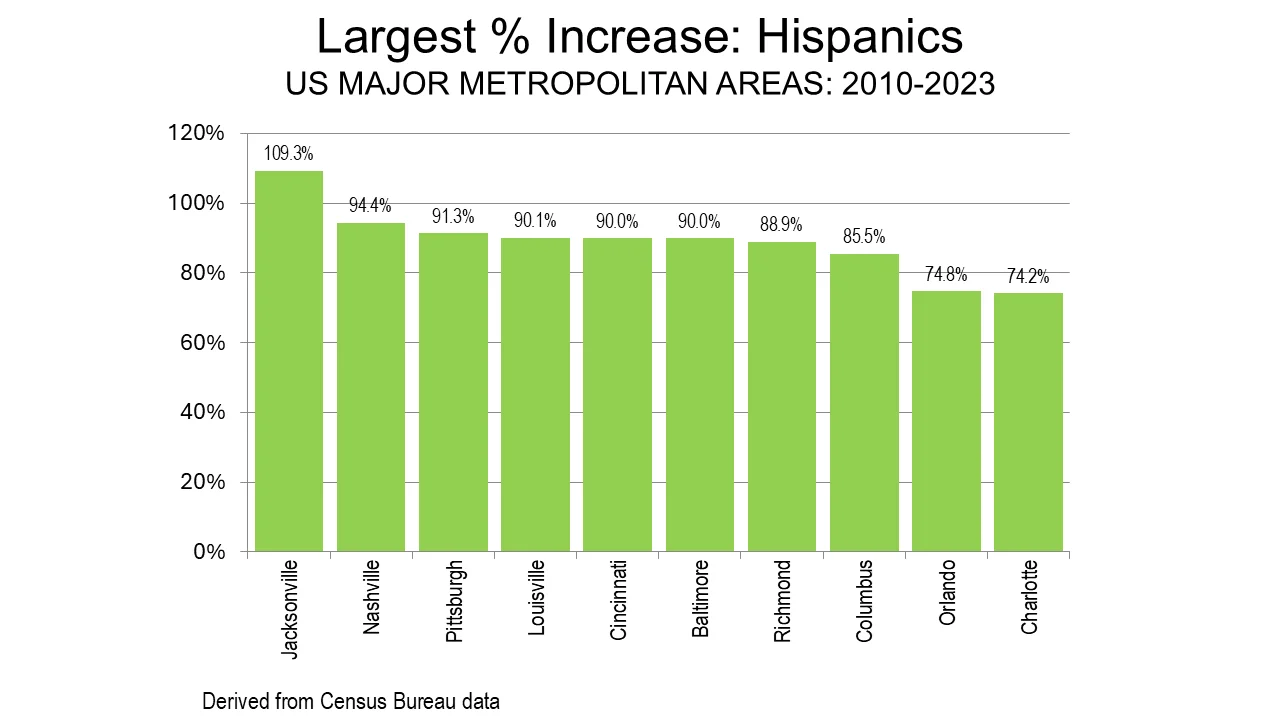

- Geographic Dispersion: Latino populations are spreading beyond the Southwest to the Midwest, Southeast, and smaller metros like Pittsburgh and Nashville, reflecting economic opportunity-seeking migration.

- Optimism Amid Challenges: Despite poverty rates (e.g., 29.6% for illegal Latino immigrants in California) and educational gaps, 75% of Latinos remain optimistic about achieving their “dream home” and the American Dream. They also value hard work (94% cite it as key to success).

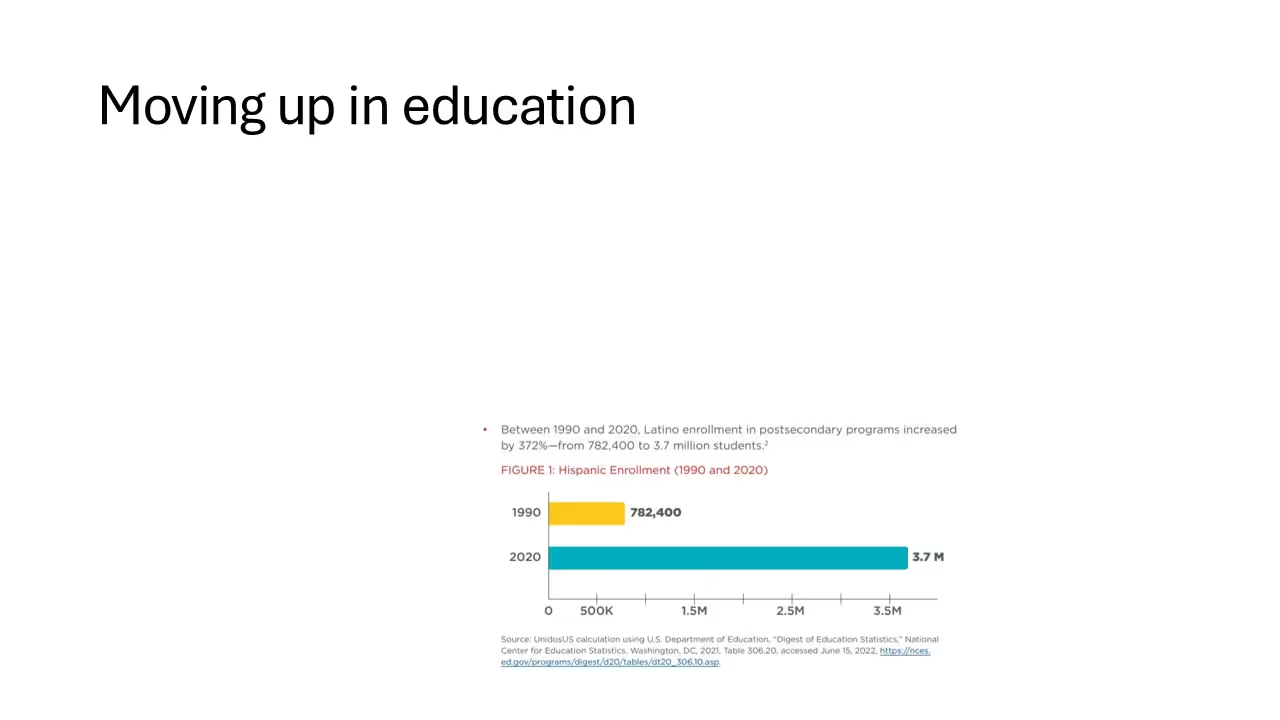

- Educational Progress and Gaps: Latino college enrollment has surged 372% since 1990, but only 16% earn bachelor’s degrees compared to 43% of whites, with lags in high-demand fields like technology.

- Entrepreneurial Growth: Latino-owned businesses, especially in construction and food services, are the fastest-growing, employing 2.9 million workers with $620 billion in sales in 2019.

- Policy Barriers: High-cost housing policies, climate-driven regulations, and anti-car mandates in states like California increase living costs and limit job access, disproportionately harming Latinos.

- Policy Recommendations: We advocate for affordable single-family housing, lower regulatory barriers, sensible energy policies, and accessible transportation to support Latino priorities like homeownership, safety, and economic mobility.

We urge policymakers to reject ideologically driven policies that hinder Latino progress, such as restrictive land use, costly climate mandates, and reduced personal mobility. Embracing policies that align with Latino aspirations rooted in work, family, and opportunity will not only empower this vital population but also strengthen America’s economic and demographic future in a competitive global landscape.

Introduction

Migration has shaped America’s history. The earliest migrants, the ancestors of the American Indians, arrived from far east Asia. Migration from the British Isles in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was voluntary but thousands of enslaved people also arrived here from Africa at the same time. The nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw waves of Germans, Italians, Russians, East Asians, Indians, and Jews.

Each group has faced sometimes brutal discrimination from the dominant majority. Many on the left see such racial prejudice as the American experience’s defining characteristic. From this perspective, Latinos are simply the latest group to live under an oppressive regime and whose lands “settlers” stole.i

Yet the Latino experience is unique and far more uplifting. Latinos differ from Europeans: notably, they migrated to a country whose territory Anglo immigrants had conquered—in Texas initially and later across the entire Southwest—and taken from them.

But contrary to the narrative of “settler colonialism,” very few of today’s Latino residents can trace themselves to earlier settlers; the vast majority are recent arrivals. Indeed, the Southwest’s entire Mexican population in 1848 was barely 48,000.ii Yet the dominant academic and progressive narrative remains one of unending oppression and seizure of land. Latinos, writes one leftist writer, have “been forgotten by the nation” and have “nothing but their angers and their hungers.” iii Like the Anglos who settled areas seized from Mexico, they too want a piece of the pie, someplace safe and prosperous for their families to live and where they can acquire wealth.

At the same time there are some on the political right who fear America’s ongoing Latinization. Some influential right-wing theorists continue to hold the notion that Latinos are intrinsically inferior to whites and Asians.iv v Others fear that the Latinos blend of Catholic and Indio culture makes them less digestible than earlier immigrants.vi

This report disputes both perspectives, and focuses instead on the progress, as well as the very real challenges Latinos face in America. The rise of Latinos does not constitute a departure from the American story; it is both wrong and dangerous to speak about them as if they were. Latinos, soon to be America’s largest ethnic group, are in a prime position to shape America’s future.vii Although the bulk are from Mexico, a large contingent comes from the Caribbean, Central and South America.

Latinos already power much of our economy; they have reshaped how we eat, have sprinkled Spanish into the language, and even created the Cinco de Mayo holiday that, as David Hayes Bautista suggests, is barely celebrated south of the border but in some ways is as American as Thanksgiving.viii

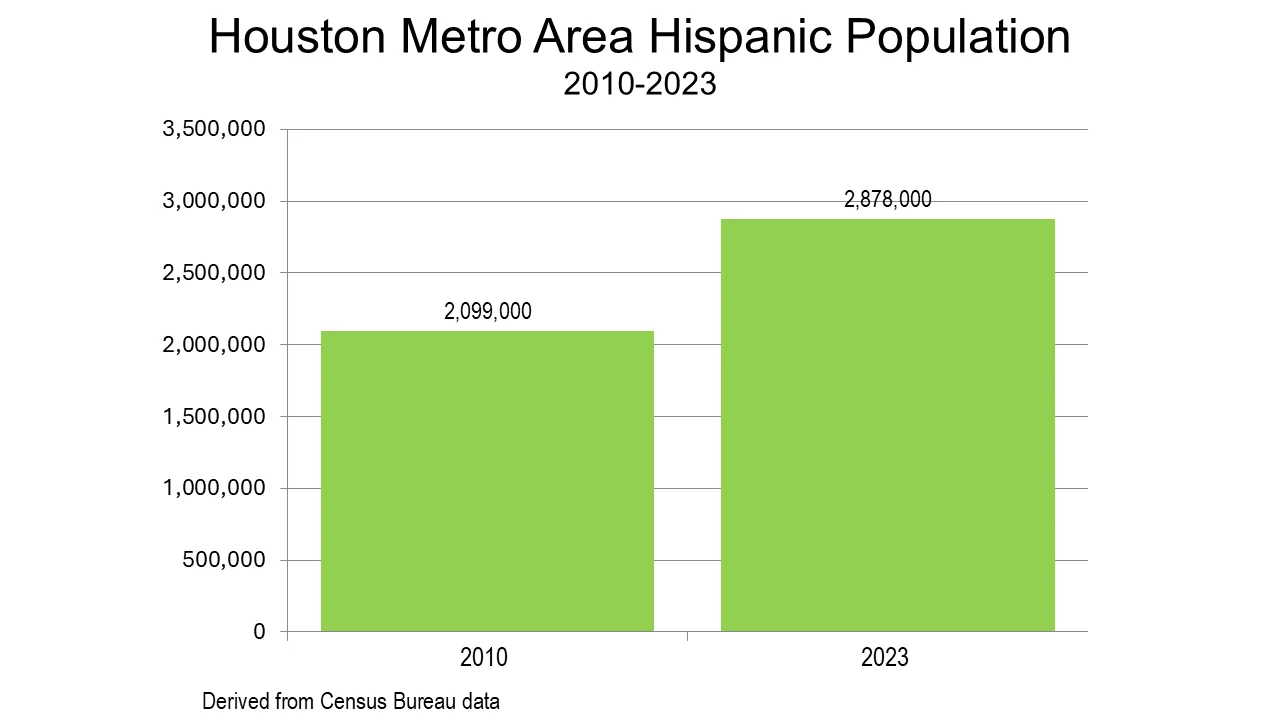

The demographic evidence is overwhelming. Since 1970, Latinos have increased from 5% of the total U.S. population to approximately 20% in 2023. Between 2010 and 2023, Latinos accounted for 56.3% of the total U.S. population growth. The Census Bureau’s most recent population projections expect the Latino population to expand by approximately 31 million between 2025 and 2060. In contrast, the total U.S. population is projected to grow by only about 26 million, while the non-Latino white population is projected to decline by 32 million. These numbers show that net population growth over the next forty years will be primarily Latino.

As Latino population numbers have grown, so has their geographic footprint. The era in which Mexamerica, profiled in Joel Garreau’s Nine Nations of North America, was largely confined to the American Southwest, has passed. Today the fastest growing Latino populations are in the country’s interior, from the mid-South to the Great Lakes.ix

The Latino economic effect has grown as they have spread across the country. In 2022, the U.S. Latino G.D.P. reached $3.7 billion and is now the world’s fifth largest G.D.P.x It grew at an average annual rate of 4.6% between 2017 and 2022, far exceeding the overall U.S. number. In Texas, which has the second-largest U.S. Latino population, the Latino G.D.P. increased by $147 billion from 2017 to 2022. Only in California, where Latino G.D.P. expanded by $154.6 billion, was this growth surpassed during the same period. Florida followed with $86 billion in its Latino G.D.P. growth.xi

Yet as Latino populations expand, they face challenges with education, housing, and economic conditions. Immigrant success in America has always depended on the country’s economic conditions and this is even more the case for the second generation, who are younger but still lag in education and economic achievement. They rely on strong industrial, agricultural, and logistics economies, as well as a higher paying service economy. States where these sectors are strongest, notably in the South and the Midwest, tend to produce better results for Latinos.xii

Overall, Latinos have made remarkable progress across the country over the last few decades. In 2019, Latinos constituted 25.9% of elementary and secondary students and 18.9% in post-secondary institutions.xiii They have gained ground overall in grade school achievement opposite their Anglo peers and Latinos have increased in terms of college students by 372% from 1990 to 2020. Latinos now represent 20% of all US college students, up from 6% (1990) and 20.3% in 2024.xiv xv Unfortunately, they lag most behind in the key fields with the best prospects—notably technology—and are only now penetrating the upper reaches of management.xvi

Perhaps most distressing has been the persistence of poverty, most wrenchingly among illegal immigrants. As recently as 1993, immigrants accounted for 14% of the U.S. population living in poverty and non-citizens 11%. Three decades later, immigrants made up almost a quarter of all people living in poverty and non-citizens over 13%. Immigrant poverty rose from 18.2% in 2018 to 22.4% in 2024, while non-citizens, including both legal and illegal immigrants, rose from 22.8% in 2021 to 28.4% last year, the highest level since 2008. Overall, Honduran (38.2%), Guatemalan (34.6%), and Mexican (27.6%) immigrants have poverty rates near or above 30%.xvii

California is a prime example of this problem. According to new Census data, in 2023 the state’s poverty rate increased to 18.9%, well above the 2021 rate of 11.0%.xviii A recent Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) report notes that in California, the current Latino poverty rate of 16.9% is well above the 2021 rate of 13.5%. Latinos remained disproportionately poor comprising about half (50.7%) of poor Californians, but 39.7% of all Californians. About 13.6% of African Americans, 11.5% of Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders, and 10.2% of whites lived in poverty.xix The most afflicted are those who are in California illegally: their poverty rate is 29.6%. A recent USC study also notes that illegal immigrants in Los Angeles, long the epicenter of Latino immigration, suffer the lowest median household income at $46,500 in 2021, compared to $75,000 among all Angelenos.xx

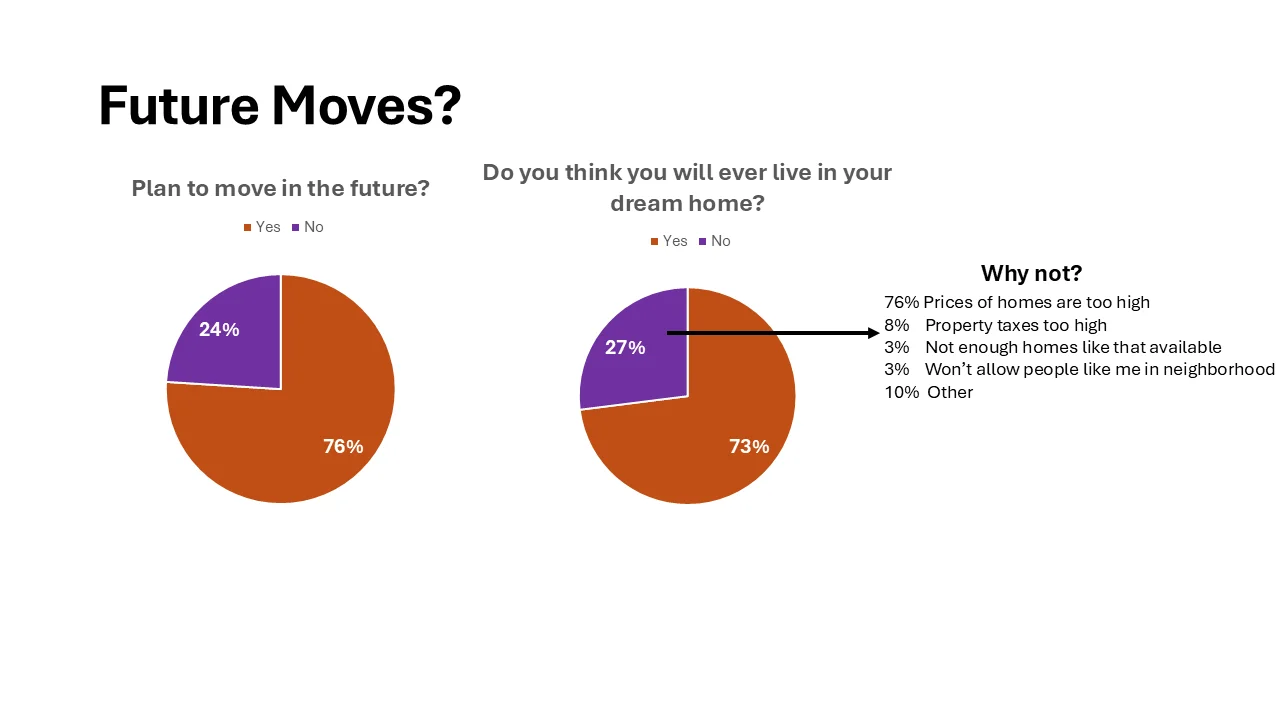

Our survey, conducted in conjunction with the University of Texas at Austin, revealed this mixed picture of both progress and severe challenges. In it, we surveyed one thousand Spanish-surnamed individuals on their attitudes about the economy, education, family, faith, and immigration. The findings are revealing, not just for their common threads, but also for the diversity within the community, including in their political views, in where they choose to live, and in their sense of future prospects, even their chances to purchase their “dream home.”

Most remarkable is Latino optimism about their chances for meeting their own aspirations. Three quarters of our respondents, for example, believe that achieving their “dream home” is possible. This is striking since it comes at a time when many Americans feel their hopes of achieving this have dropped dramatically.xxi

This optimism is crucial during a time of deep-seated pessimism across the country, which our survey and focus groups showed as well.xxii Latinos still believe in and cherish the American dream, and a majority believe they can sill achieve it.xxiii When asked what factors are most important to succeeding in the U.S., 94% said “a strong work ethic and working hard.”xxiv

We also conducted two focus groups, one in San Antonio (Texas) and one in Riverside-San Bernardino (California), with selected Latino leaders, businesspeople, educators, and academics, that focused on education and economic development. Viewpoints varied, but the focus groups addressed many common themes, including patriotism, faith, family, and entrepreneurialism.

Many of the people we interviewed had concerns, most notably on deportations of Illegal immigrants. Latinos are far less in favor of the current I.C.E. drive against non-criminal illegals than most Americans, although they are far from unified in their political inclinations.xxv But all Americans, whatever their views on immigration, need the Latino community’s energy. Low fertility and a rapidly aging population are hallmarks of our period, and Latinos are a young, dynamic population capable of sustaining the American experiment.

But Latinos represent more than just numbers, their optimism is critical—even amidst what one interviewee labeled I.C.E.’s “war” against Hispanics. In one particularly poignant session in Riverside, each of the panel’s eleven members described their own concerns about the breakup of hard-working and law-abiding families. Yet for all their concern, at the end of the day when we asked them if they were optimistic about the future, all eleven enthusiastically said “yes.”

The Demographic Ascendancy

Latinos, as the vanguard of America’s demographic future, matter. For much of the past three hundred years, Latinos have been a largely regional group, concentrated overwhelmingly in the Southwest. Some upper-class remnants from Spanish and Mexican days excepted, most of the increasingly Anglo-dominated region marginalized and disdained them as a source of cheap labor during that period.

The early 19th century author Thomas J. Farnham described “Los Hombres Californios” as “somewhat humanized,” proverbially lazy, and shiftless.xxvi William Wilson McEuen, in a 1914 study, described them as “the most degraded race in this city.”xxvii In Texas, where ties to Mexico were far more evolved, the Houston Morning Star in 1839, four years after independence, complained about “idle thieving vagabonds” who constituted “a miserable remnant of our conquered enemy.”xxviii

.jpg)

By 1900, for example, the still small, Spanish-founded city of Los Angeles was barely Latino at all. In the aftermath of the Mexican revolution (1910-1917), a massive wave of immigrants arrived in the U.S., many of them to Southern California. The peak Latino share for the city of Los Angeles was 48% in the 2010 census, falling to 47% in 2020. Similar patterns hold in Houston, the other pole of Garreau’s Mexamerica. Latino populations, who suffered from segregation, were still relatively marginal well into the 1950s, even though most were American born.xxix

In 1960, Harris County, which includes Houston, was barely 10% Latino. Today that percentage is four times higher. Patrick Jankowski, former chief economist for the Greater Houston Economic Partnership, notes that the past decade has seen the area add over one million people, the majority of them Latino and barely one-tenth Anglo.

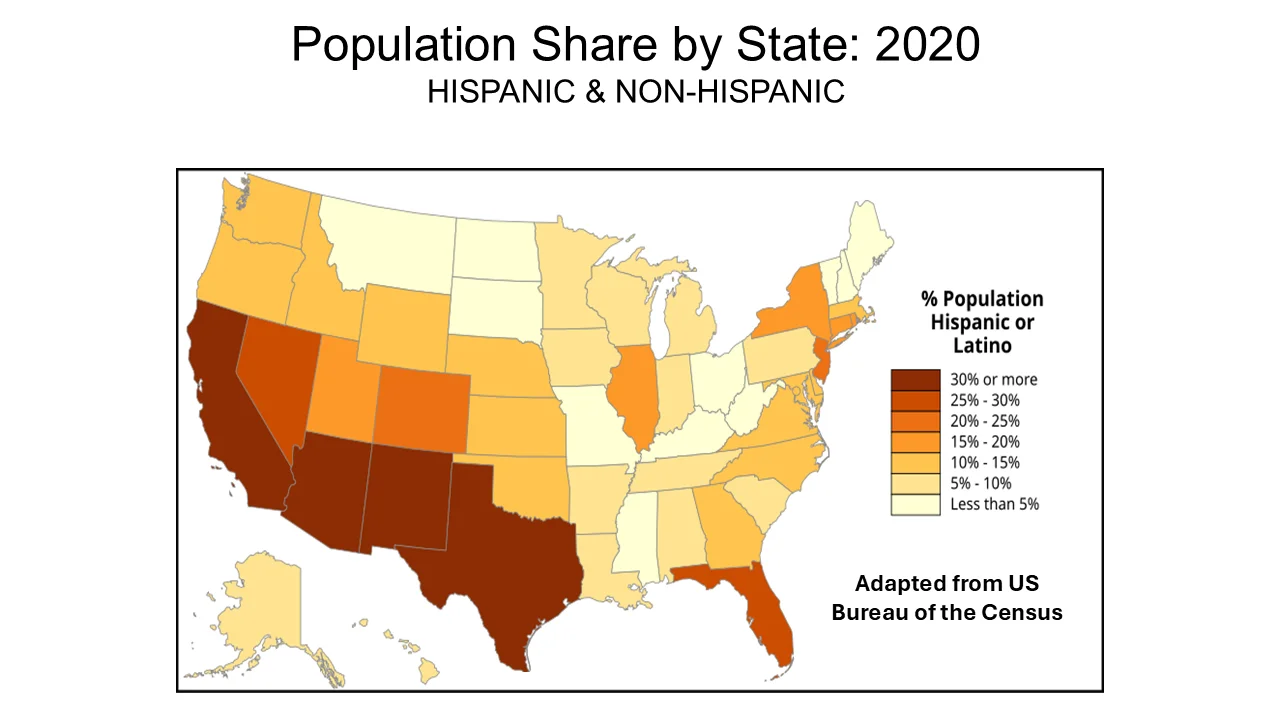

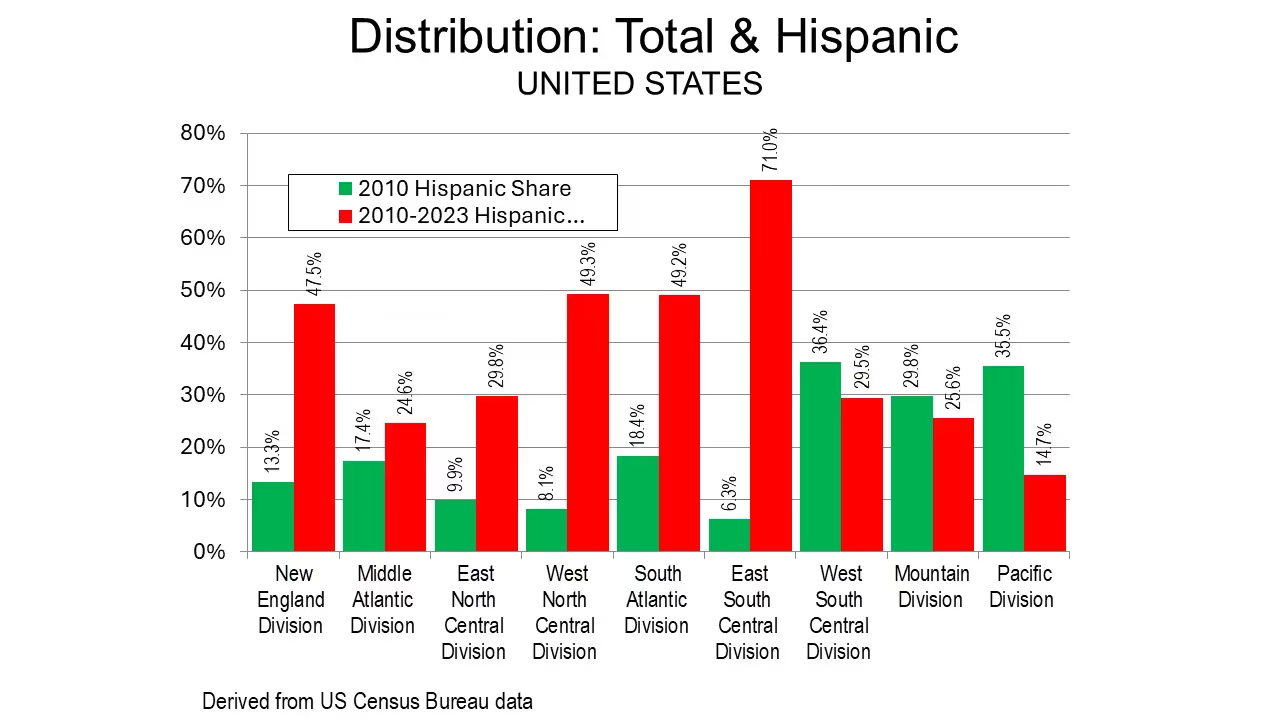

The Southwest is still the most Latino part of the country, but the population has spread across the entire country in the past few decades. Latinization, if you will, is now a national phenomenon.xxx The strongest Latino population shares continue to be in the West South Central (largest state Texas), the Mountain, and the Pacific census divisions. These are the only census divisions that share a border with Mexico. The clear trend is for Latinos to move ever further from the Mexican border. Not surprisingly, the Latino shares in the other census divisions are lower. Yet, their percentage increases are generally higher. There are already large concentrations of Latinos on the East Coast, where their share is highest in Florida (27%), followed by elevated shares in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, driven by high shares of Latinos in the New York metropolitan area.xxxi

Increasingly, however, Latino population growth is strongest not in these regions, but in places like the Southeast (outside Florida) and the Midwest, where they were underrepresented in the past. The biggest growth was in states like the Dakotas, Maine, Montana, and Tennessee. Regionally, Latino growth was strongest in The East South-Central division. Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama experienced the strongest Latino growth during this period, despite having the lowest Latino share overall. The new Latino “boomtowns” are located largely in smaller, vibrant cities not only in the sunbelt, like Nashville, Charlotte, and Jacksonville, but also in dynamic former “rustbelt cities” like Pittsburgh and Columbus. Significant growth also has occurred in New England (Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine), the upper Midwest (Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin), as well as the South Atlantic.

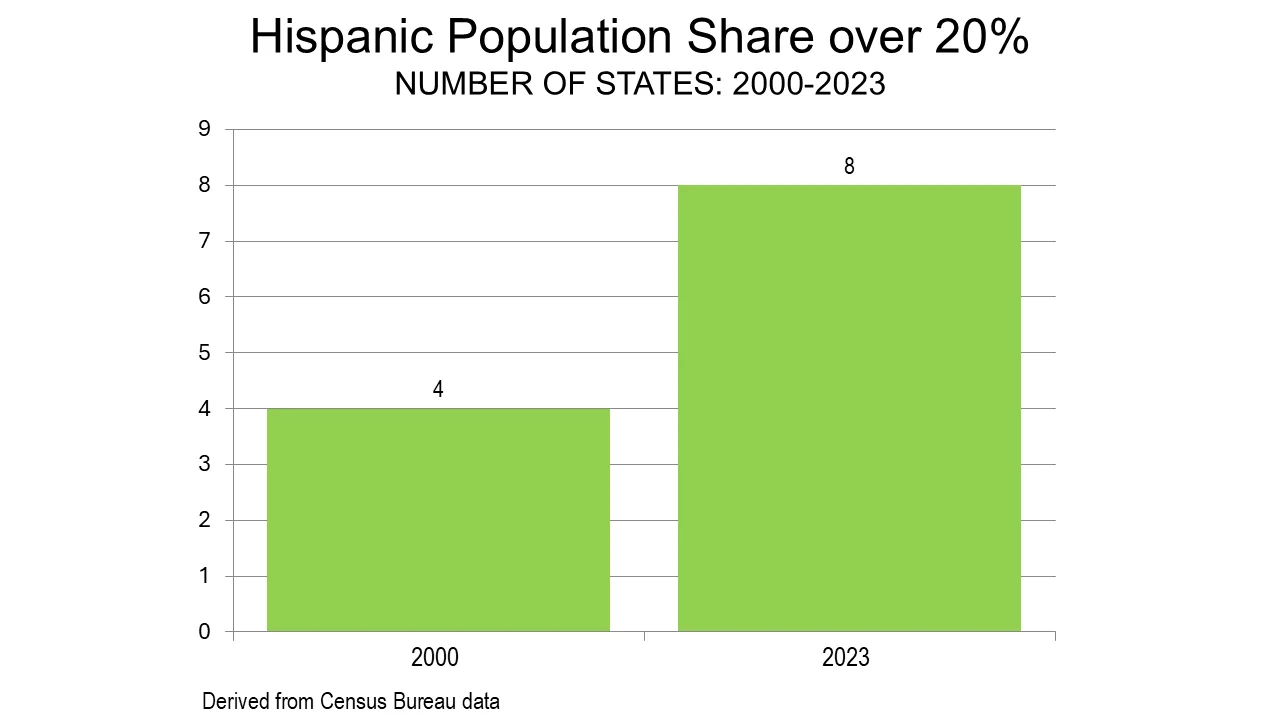

Gradually, a more national paradigm is replacing the old Southwest one. Latinos in 2000 were more than 20% of the population in four states. Today they are more than 20% in eight states, and by 2030, the Census Bureau projects that Latinos will account for 22% of the national population.

Latinos now favor smaller metropolitan areas like Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Richmond, Jacksonville, and Columbus. They are transforming even the most iconic traditionally Anglo areas. We can see this even in Nashville, America’s country music capital. As recently as 2000, less than 3% of metro Nashville’s population was Latino, but by 2020, that percentage had more than tripled.

Less noticed has been the shift in Latino population growth in smaller metropolitan areas. In fact, Latinos have been migrating away from big cities like Los Angeles over the past decade as they move not just to large metropolitan areas and suburbs, but to smaller towns, cities, and exurbs of major metros. Farm work does not drive this movement; only 4% of Latinos lived in rural areas, according to the 2020 census.xxxii

Seemingly unlikely places like Pottstown, PA; Scranton Wilkes-Barre, PA; Hagerstown, MD; Coeur d’Alene, ID; and Fargo, ND are now home to sizable Latino populations. This is something of a reversion to the past. According to the 1890 census, for example, North Dakota’s foreign-born constituted 45% of the population. This was the highest foreign born percentage among the states in the Union at that time. After years in which few immigrants came, North Dakotan immigration is increasingly diverse: growth among Latinos is 175%, the largest of any state according to Census Bureau data from 2010 to 2023.xxxiii

Making America’s future

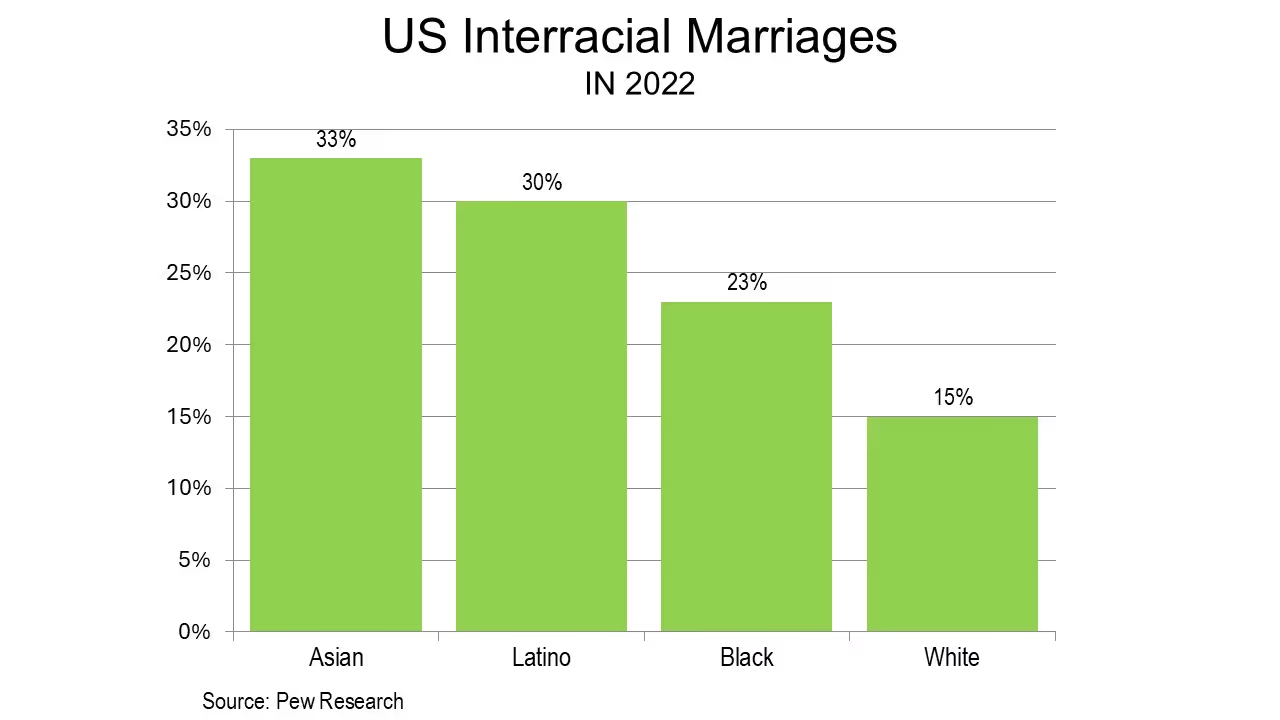

Latinos are also increasingly intermarrying with Anglos as well as with other races. In the U.S. in 1980, an estimated 26% of interracial newlyweds included a Latino. By 2022, the figure had increased to 30%. Among native-born Latinos, 41% of marriages were interracial, compared to 11% among those foreign-born.xxxiv This points to a greater propensity toward interracial marriage among Latinos who have lived in the United States longer.

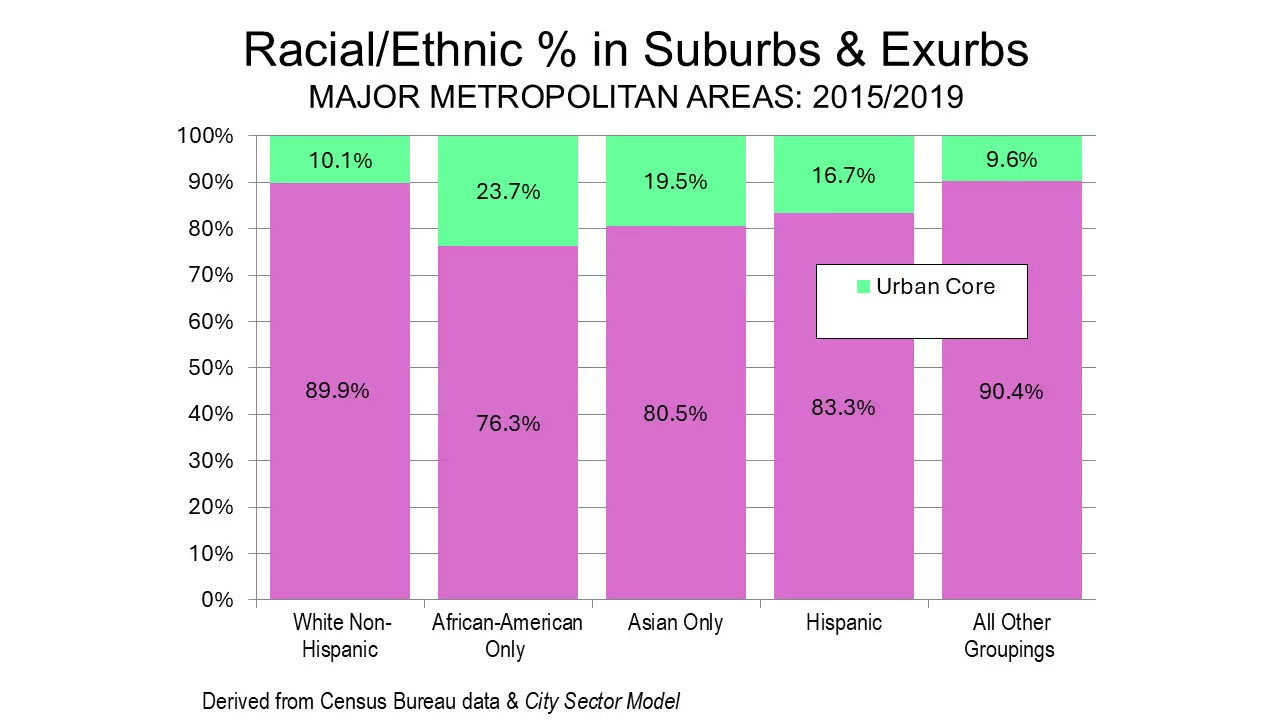

As they marry other Americans, Latinos are increasingly living in suburbs and exurbs rather than in core cities. Between 1990 and 2010, the percentage of Latinos living in suburbs grew from 47% to 59%.xxxv This reflects in part their fundamental aspiration, which our survey showed to be the purchase of a single-family house. Monica Garcia, a special education teacher, told our San Antonio focus group that when her family first came from Mexico, they gravitated to the suburban areas on the outskirts of the city. People are starting to live in the outskirts in all directions from the city,” she said, “which is really nice because of developments that are happening. So now there are a lot more options for families.”

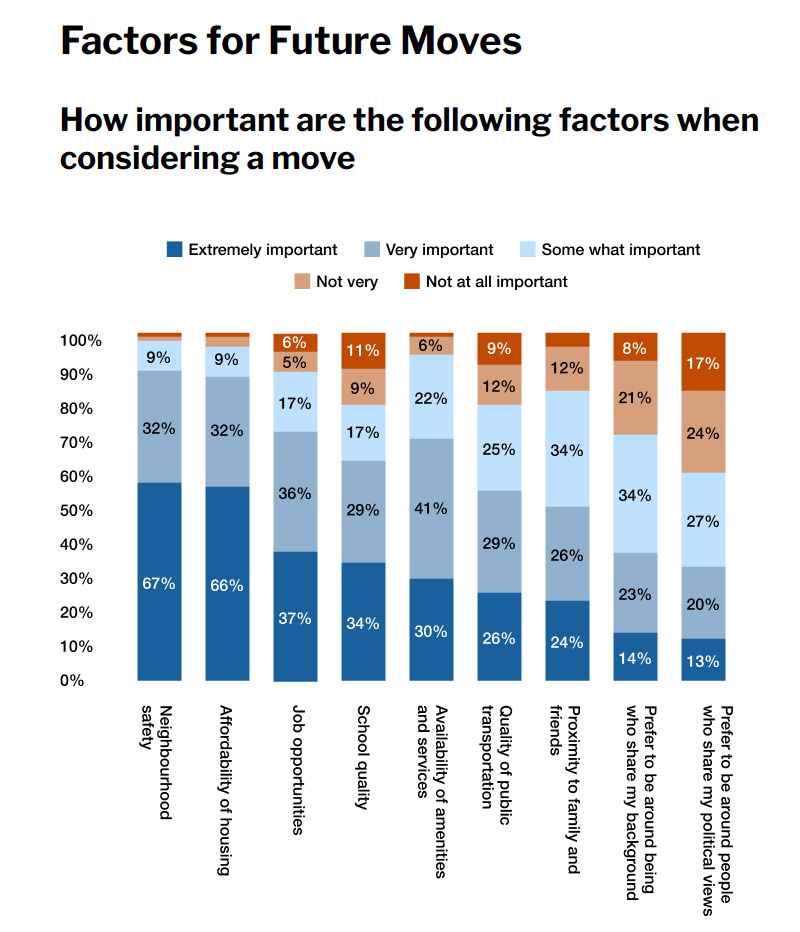

Essentially Latino patterns parallel those of America in general. It is hardly a response to “white flight” but towards ever growing integration with the geography of the overall population. Greater geographic mobility also suggests a reduction in things such as redlining, which was particularly imposed against ethnic minorities, but are now largely a vestige of the past.xxxvi Our survey found that Latinos prioritized common factors like safety, affordability, and access to jobs and schools. At the bottom of the list was a desire to live with other Latinos or with people who shared a common political viewpoint.

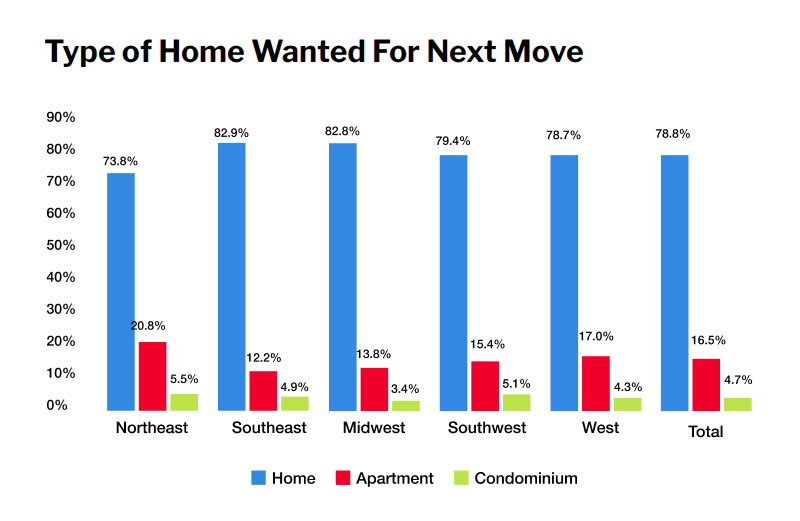

The most critical motivation for Latinos, both from their migration patterns and preference, lies in economic factors, particularly in helping to improve their family’s circumstances. Owning a home, as opposed to an apartment, took a high priority in all regions and the vast majority wanted a single-family residence.

The future workforce.

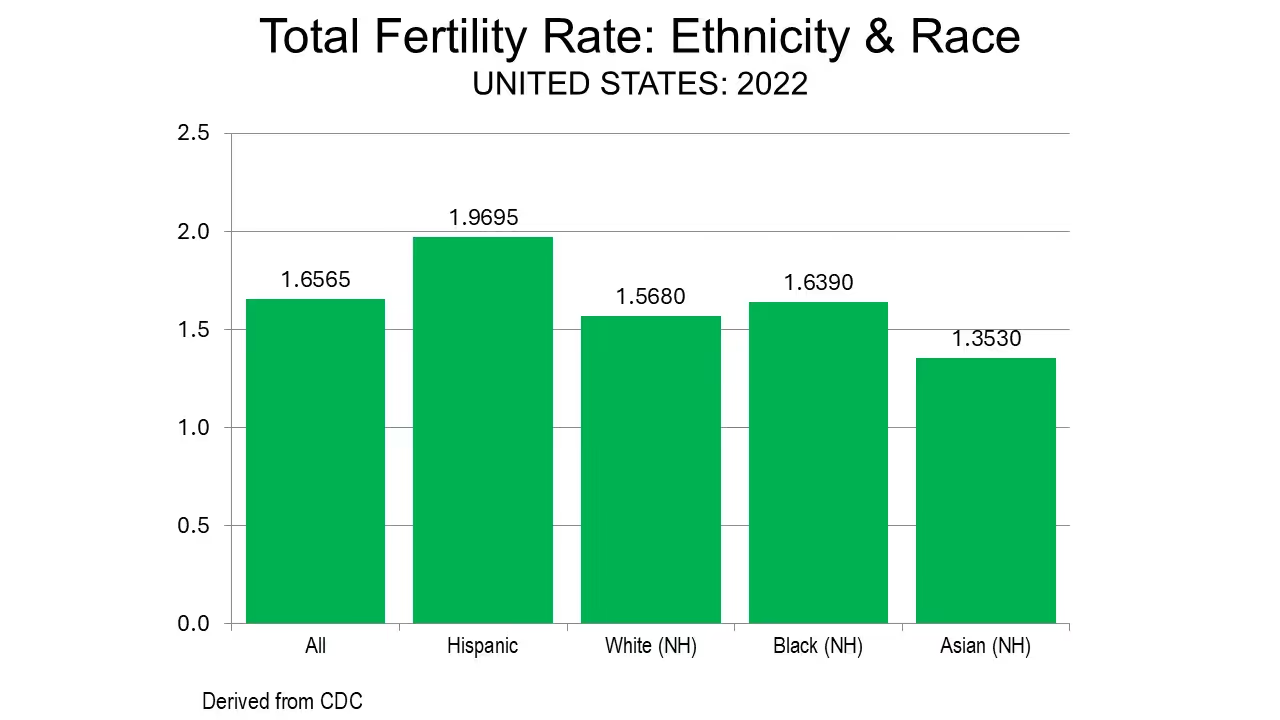

Whether to the Sunbelt or small Midwestern metros, our survey showed that Latinos move primarily for work opportunities. On the plains, in the barrios of San Antonio and Los Angeles, and in Northwest Arkansas, Latinos’ biggest effect will be in sustaining the workforce, which has been on a downward trend in recent decades. Although their fertility rate and that of Americans in general have declined from earlier decades, U.S. Latinos continue to have high birthrates.

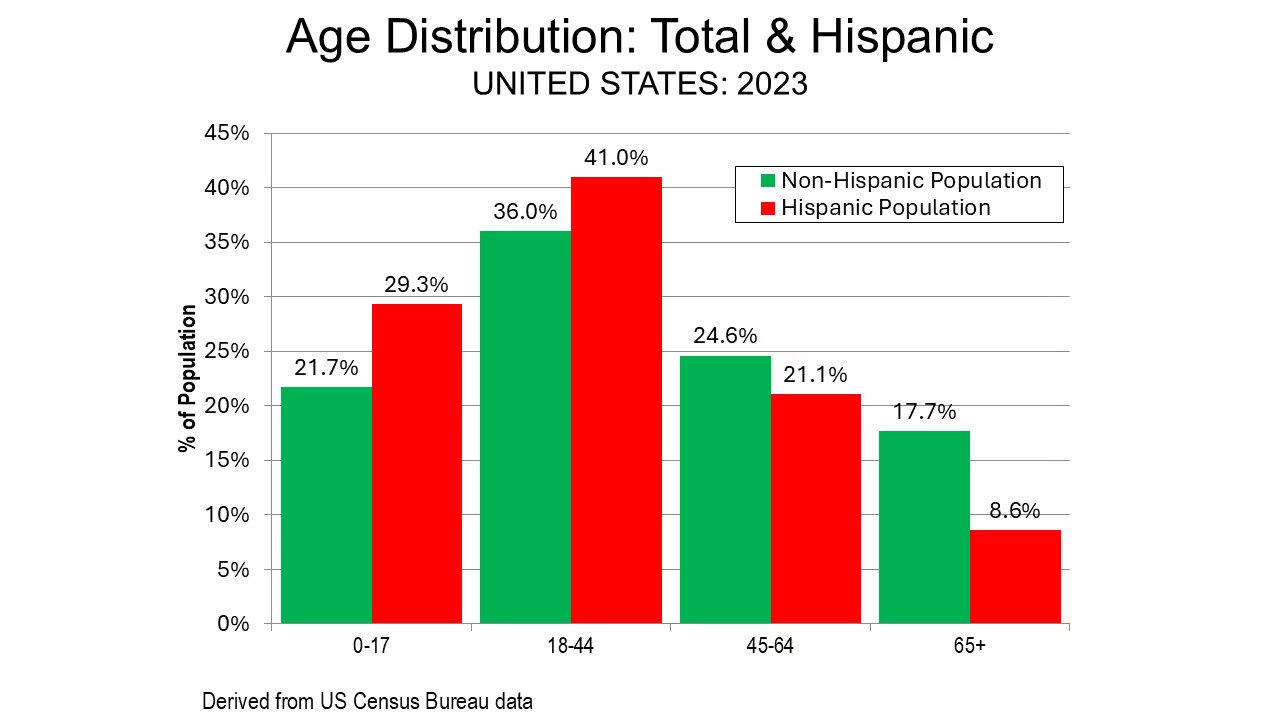

The Latino population is significantly younger than the rest of the U.S. population. Some 29% of Latinos are under age 18, compared to 22% for the rest of the population. Among adults aged 18-44, 41% of Latinos fall in this age group compared to 36% of the rest of the population. Conversely, Latino have a smaller share in the 45–64 and 65+ age categories compared to the non-Latino population. Latino birthrates have certainly dropped, but far less than those of other ethnic groups.

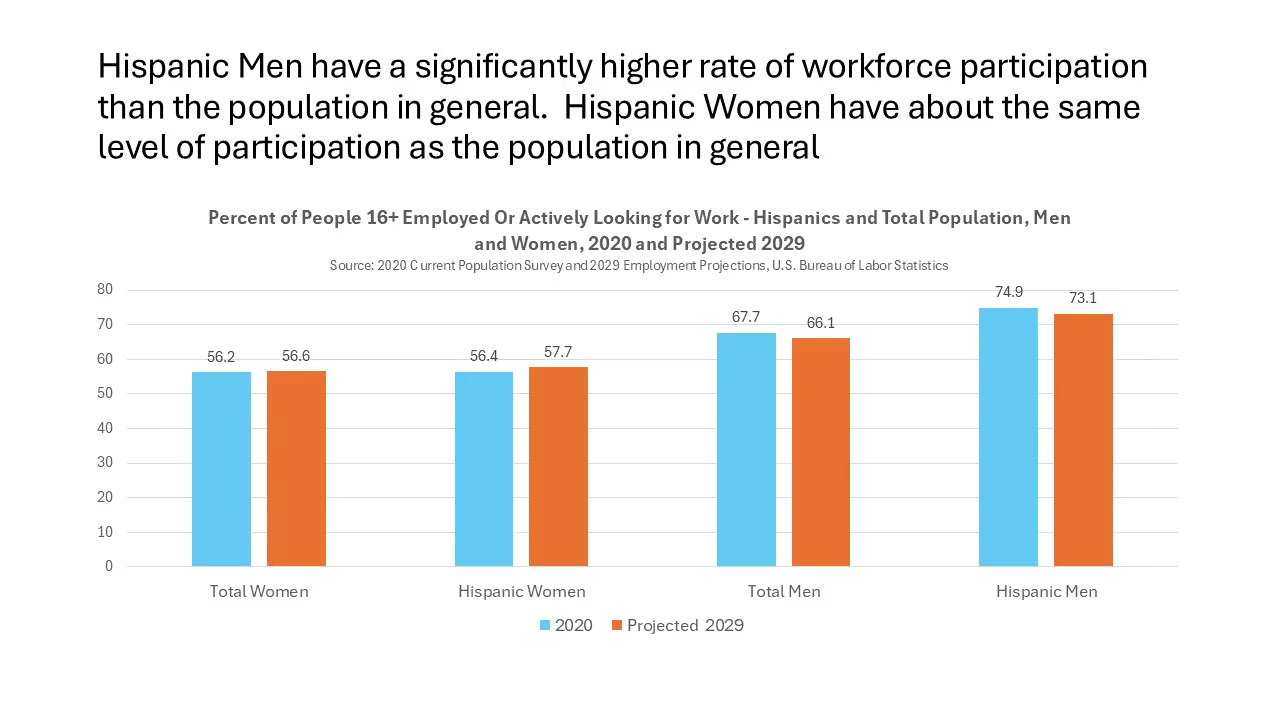

Given their generally younger profile, they are destined to play a significant role in the U.S. workforce, since their numbers will steadily increase over the years. In California, Latinos represent about 37.7% of the workforce and demographic trends suggest they will constitute more than half by 2030.xxxvii Increasingly, it is the foreign born and their offspring who can fill labor gaps. Latinos also tend to be more engaged in the labor force; their participation rate is 67.3%, which is higher than the overall rate of 62.7%. More Anglo Americans are on the employment sidelines.

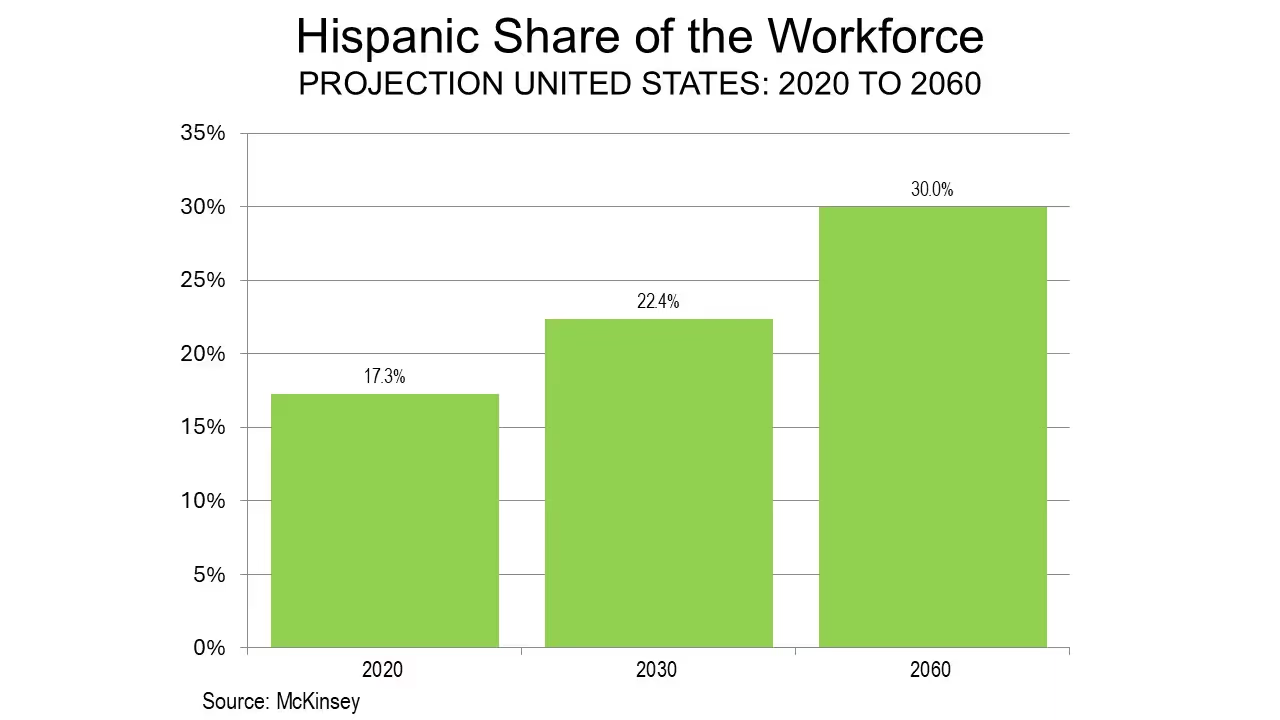

In 1990, Latinos accounted for approximately 10.7 million workers. That figure rose to 29 million by 2020 and is projected to reach nearly 35.9 million by 2030.xxxviii Projections indicate that between 2020 and 2030, Latinos will account for 78% of new U.S. workers, in contrast to the non-Latino workforce, which slowed from 1990 to 2020.xxxix Overall, the Latino share of the workforce, is expected to double to nearly 30% by 2060.xl

Immigration policies may slow this growth, but the Latino workforce of the future is already here. The percentage of Latinos born abroad peaked in 2000. Today the vast majority are English speaking; even in multicultural Los Angeles barely one in five Latinos in households without an immigrant speak Spanish at home, while three-fifths of all third generation Latinos speak only English.xli

Overall, Latinos are destined to become an increasingly a critical component of the American workforce. Two-thirds of Latinos are now American-born; that number is expected to rise to more than three-quarters by 2060.xlii American prosperity in the 21st century could depend in large measure upon Latino labor.

The Economic Equation

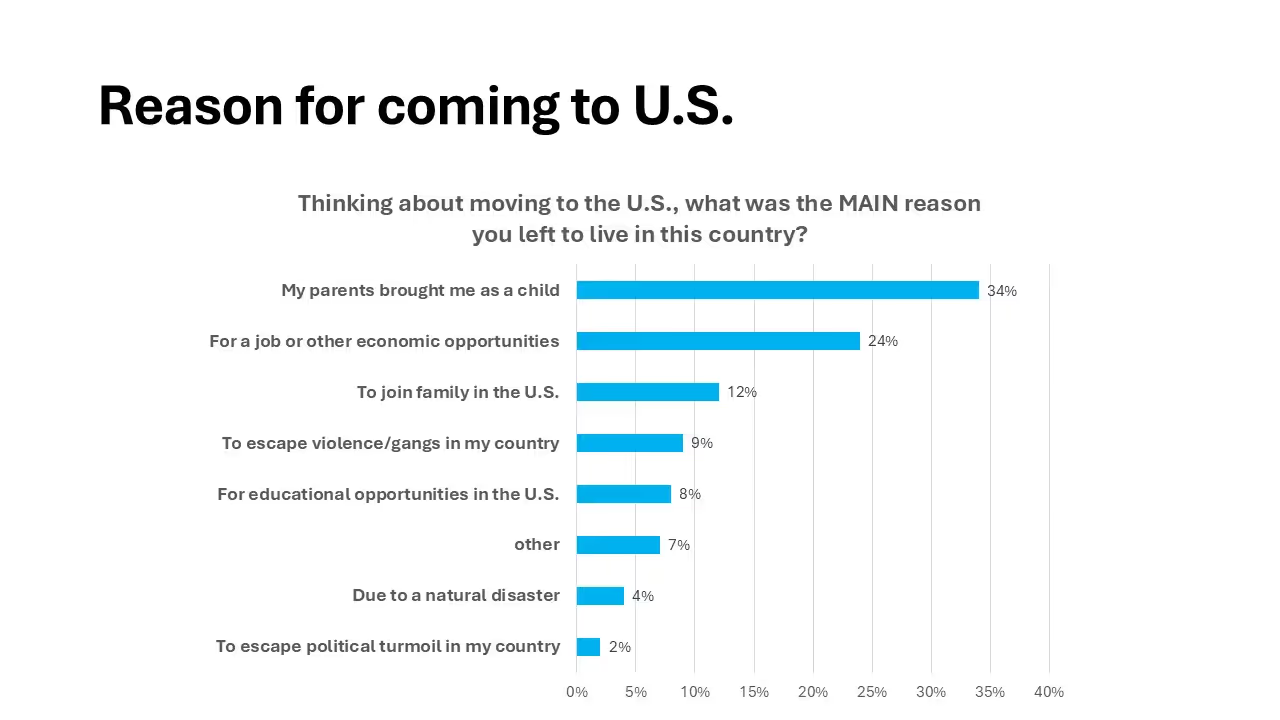

Like most immigrants, Latinos have come to America for predominately economic reasons. For much of the 19th century, they came across a mostly open border, flowing back and forth across employment opportunities. In the early 20th century, Latinos, primarily from Mexico, came to work during the First World War and in the aftermath of Mexican Civil War, only to be sent back during the Depression, and then invited back during the Second World War.

Until recent decades, it was mostly along the Southwestern border, in areas originally settled by Spain and controlled by Mexico, that felt Latino economic influence. The last century saw significant Latino communities begin to move into the interior in earnest, notably to cities like Chicago and Kansas City, where they worked mostly in lower wage jobs in manufacturing, agriculture, and service. By 2020, Latinos dominated many critical fields, accounting for three quarters of dry wall installers, three-fifths of roofers and carpet installers, and half of all housekeepers.xliii

This follows a long, historic tradition, where relatively low-paid workers do the demanding work necessary for an expanding economy. America’s miners, for example, came first from the British Isles, but migrants from eastern Europe followed them.xliv Italians dominated the stone cutting industries used in building cities and infrastructure.xlv Jews worked as peddlers and in garment factories, alongside undocumented Chinese workers.xlvi

Commentary at the time suggested that these immigrants would remain poor, exploited, incubators of criminality. These suppositions led to the severe immigration restrictions in 1924, particularly on those from outside northern Europe.xlvii More recently, nativists like Peter Brimelow claim that recent immigrants from poor countries such as Mexico and El Salvador are doomed to “economic failure”xlviii

But history suggests something different. All these groups later ascended the economic ladder and now do better than the extant native-born white population in many cases.xlix Latinos and other recent immigrants, we argue, are already experiencing something of what author Joel Millman has described as the “American alchemy.”l

Yet today’s Latino community faces some unique challenges, particularly in an economy that may have decreased need for strong backs and nimble fingers. Jobs requiring extensive manual labor have dropped to 22% of all jobs in 2025 from 35% fifty years ago.li As the employment picture changes, we must ensure the escalator of opportunity—particularly in home ownership, well-paying blue-collar jobs, and small businesses—continues moving as it has for other immigrants and racial minorities.

Latino work ethic

Latinos’ strong work ethic is a critical economic factor, both for their community and the country. Workforce participation among Latinos has seen steady gains over the past five years across all the prime income-earning age groups. Approximately 80% of Latinos aged 25-54 in America are employed. Employment among 20- to 24-year-old Latinos lags as does that of the prime working age groups, but has seen increases over the past five years, bucking other ethnic groups’ flat trend. The 2023 Latino rate of workforce participation for people 20-24 is slightly higher than that of the total national level for all ethnic groups (73% vs. 71%).lii

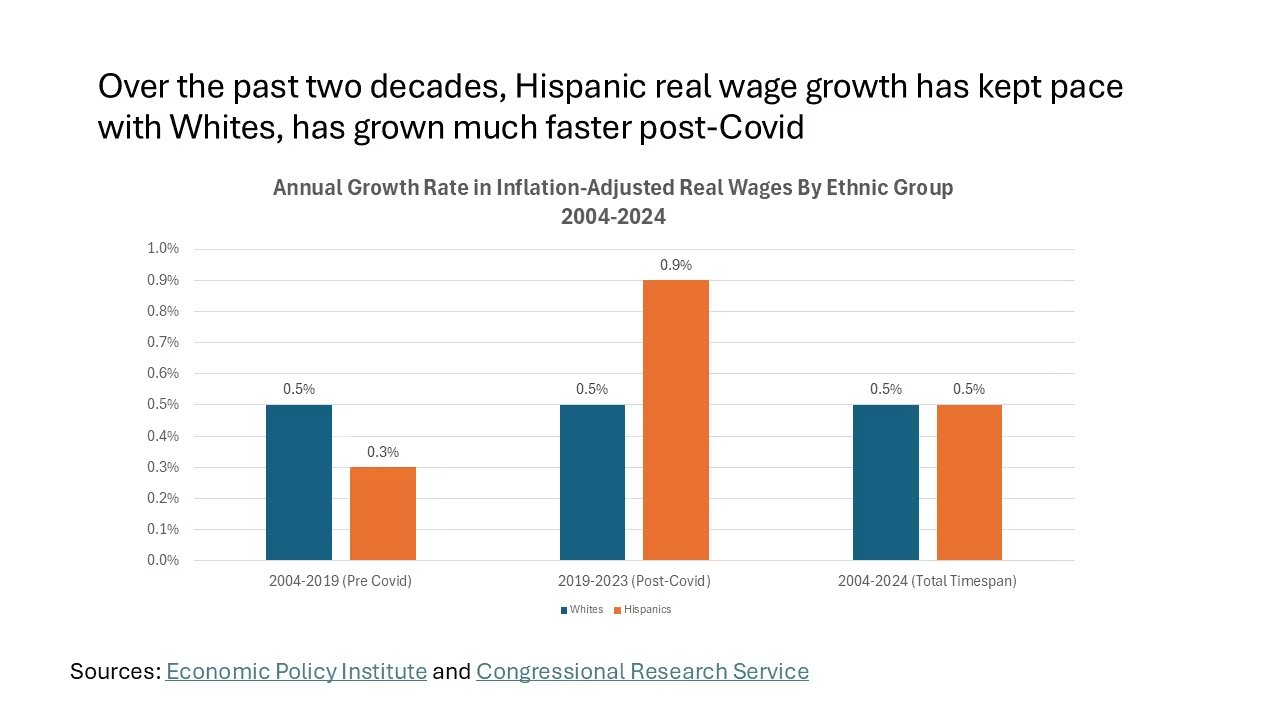

Through their labor and increasing population numbers, Latinos are already a primary U.S. growth engine. In total, the Latino engine accounts for a larger G.D.P. than all but four countries.liii If taken as on its own, this economy has been among the world’s fastest growing, more like China or India than Europe or even the rest of the U.S. Overall, Latino wages are growing faster than the national average.

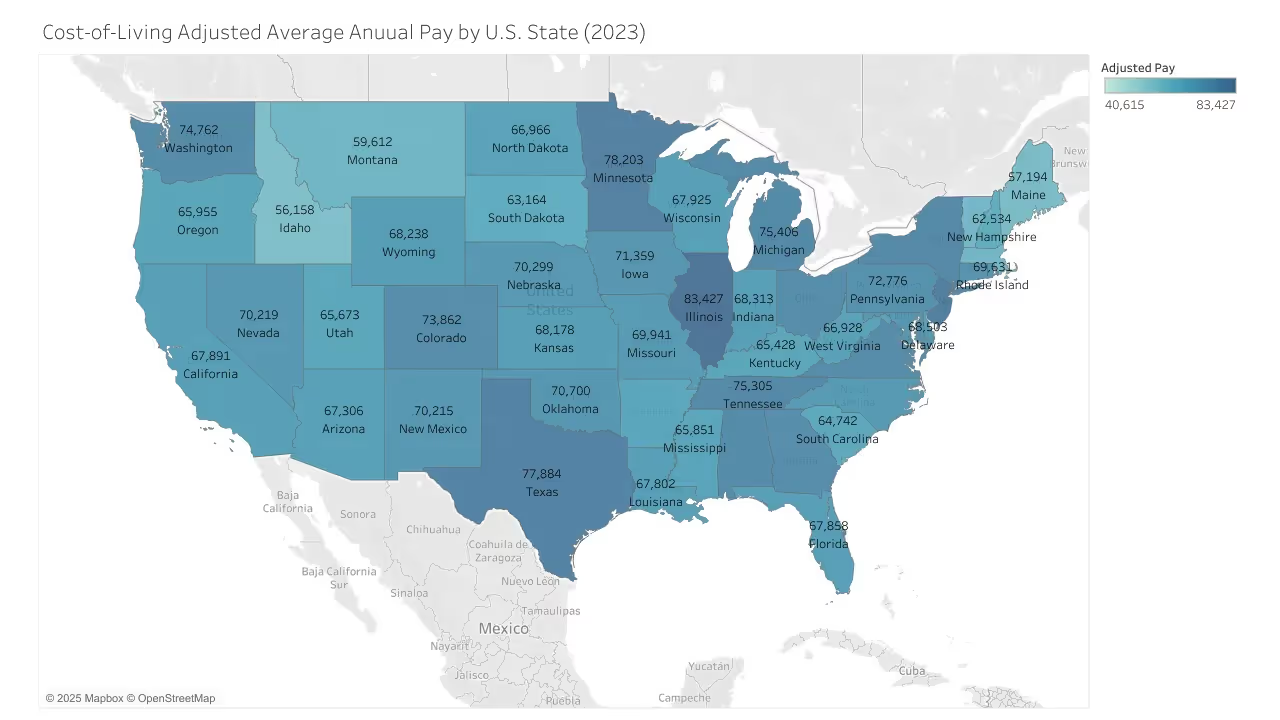

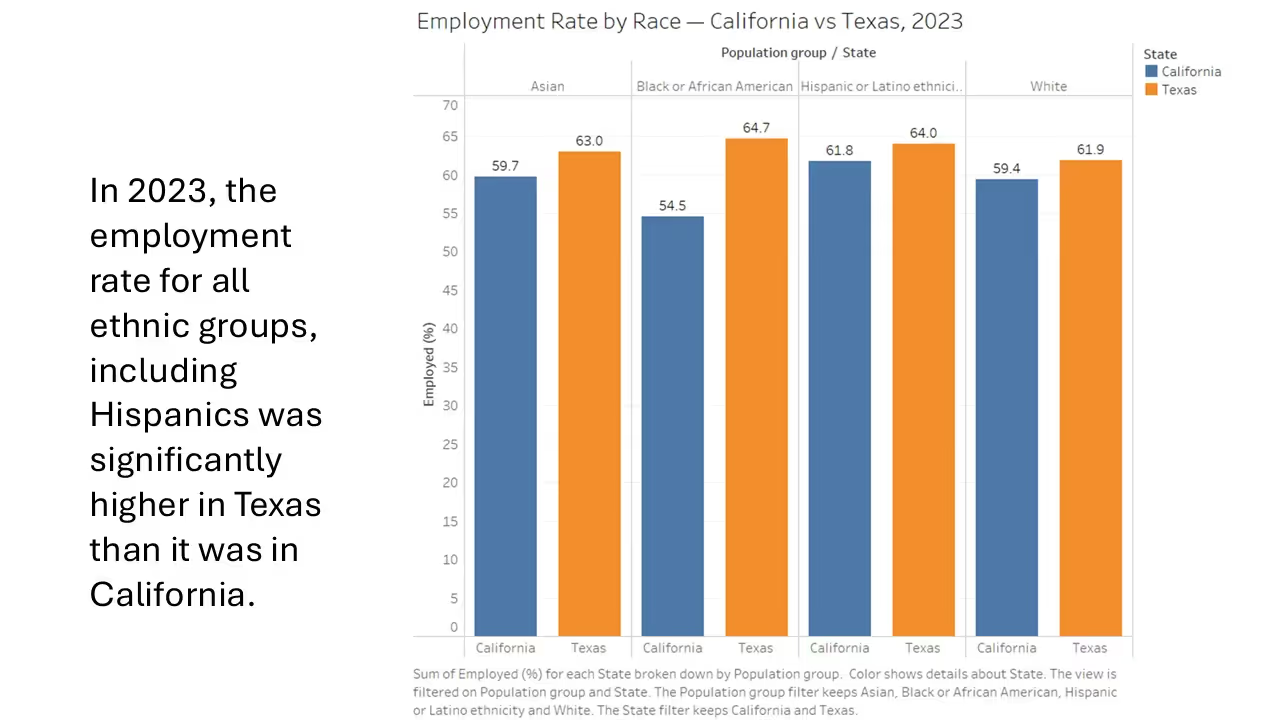

The primary Latino states—California, Texas, and Florida—feel the effect most deeply. Yet as we saw earlier, there is a clear shift: Latinos thrive in red, low-cost, low-tax states, including such unfamiliar places as the Midwest. Adjusted for costs, Latinos in Texas, for example, make $10,000 more per capita than their California counterparts. They also fare better in many Midwestern and Plains states such as Minnesota, Illinois, Iowa, and Nebraska.

One key factor lies with the cost of living. In 2023, the cost of living in California was 34.5% higher than the national average and the cost of living in Texas was 7.0% below the national average. That translates into a major difference in buying power among the states. This is true across all ethnic groups, which helps to explain the migration of people from California discussed above, to less expensive states such as Texas.

Yet even if Latinos are doing well in aggregate, the issue of trajectory remains. Historically, Latinos have been associated with agricultural and transportation occupations, but today, the largest percentage of Latinos work in sales, service, and management occupations. This has been particularly useful for Latinas, who have moved up into the professional ranks far more than their male counterparts. Indeed, from 2010 to 2021, U.S. Latina’s real incomes grew by 46.0%, compared to only 18.5% for non-Latino females.liv

Despite Latina prevalence in management and professional jobs, however, overall growth among Latinos in these occupations has lagged other ethnic groups since 2018. This also applies to certain well-paying professions like airline pilots, engineers, surgeons, C.E.O.s, lawyers, accountants, and auditors.lv The greatest challenge is among illegal immigrants—over 70%are Latino who tend to have the lowest levels of educational achievement.lvi Legal immigrants do far better, and they have boosted their educational levels over the past decade.lvii

Overall, the migration picture is very mixed. Although many legal immigrants, including those from Mexico, have high education levels, the general trend—largely attributable to the Biden-era migrant surge—has been for all immigrants to be unprepared for professional careers. This reality potentially mires them at the bottom of the employment chain.lviii

Three keys to upward mobility

In the immediate future, a few areas present the best opportunities for Latino economic progress. First is small business, where Latinos now have the fastest growth of any ethnic group. Next is homeownership, which has long been a critical route to acquiring family wealth. There is also the unique opportunity the growing demand for skilled blue-collar labor presents. Finally, the concentration of Latinos in the “tangible economy” may offer better opportunities than the business service and tech economies. Particularly with the introduction of artificial intelligence, college graduates face a job market getting tougher even for those with expensive advanced degrees. AI’s rise increasingly threatens their jobs, including in finance, business services, and even in “creative” professions that historically have clustered in cities. lix

The rise of Latino business

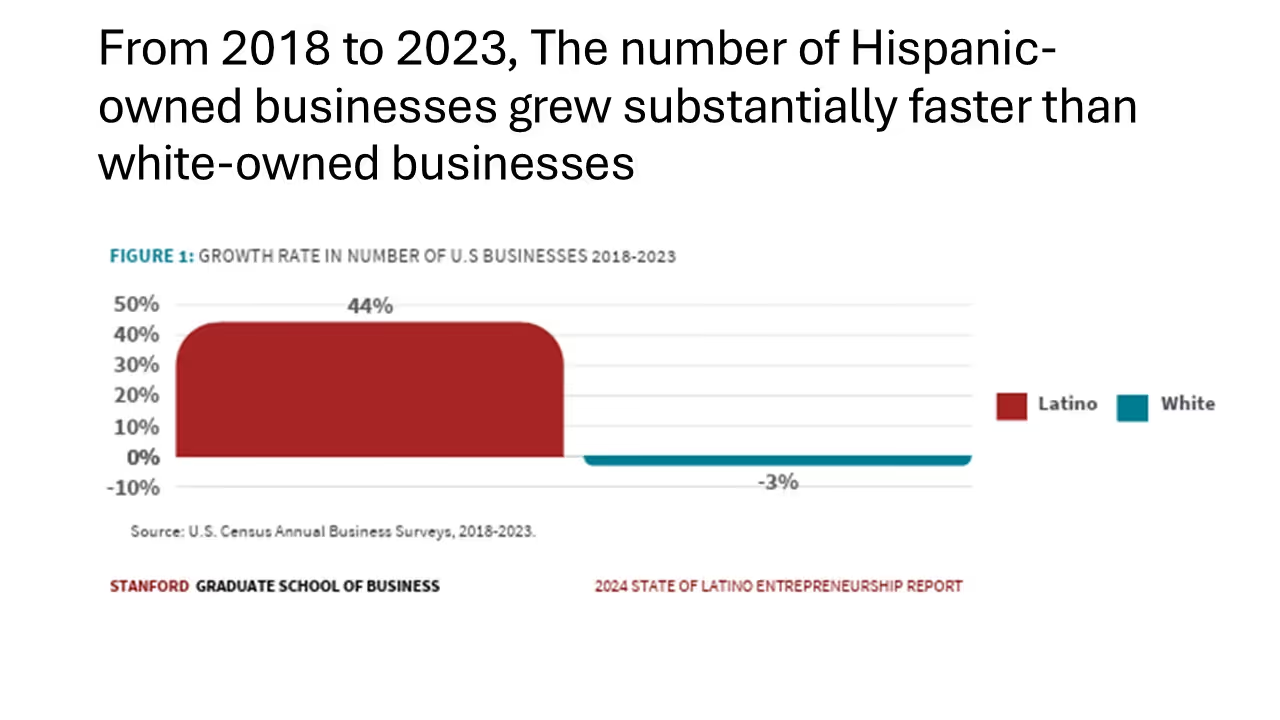

The most remarkable progress has been on the entrepreneurial frontier. Latino business owners in 2019 employed 2.9 million workers and sales in Latino-owned businesses totaled more than $620 billion. The large majority of those businesses were small firms with no employees. Latino-owned businesses in the country of all sizes totaled 346,836 in 2019. That number increased to more than 406,000 by 2021.

The growth rate of Latino-owned businesses has been high across the country. Latinos start more businesses per capita than any other U.S. racial or ethnic group.lx Overall, Latino-owned businesses are also growing faster in terms of revenues than white-owned businesses nationally. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2022 annual business survey, Latino-owned businesses represented about 8% of all U.S. businesses.

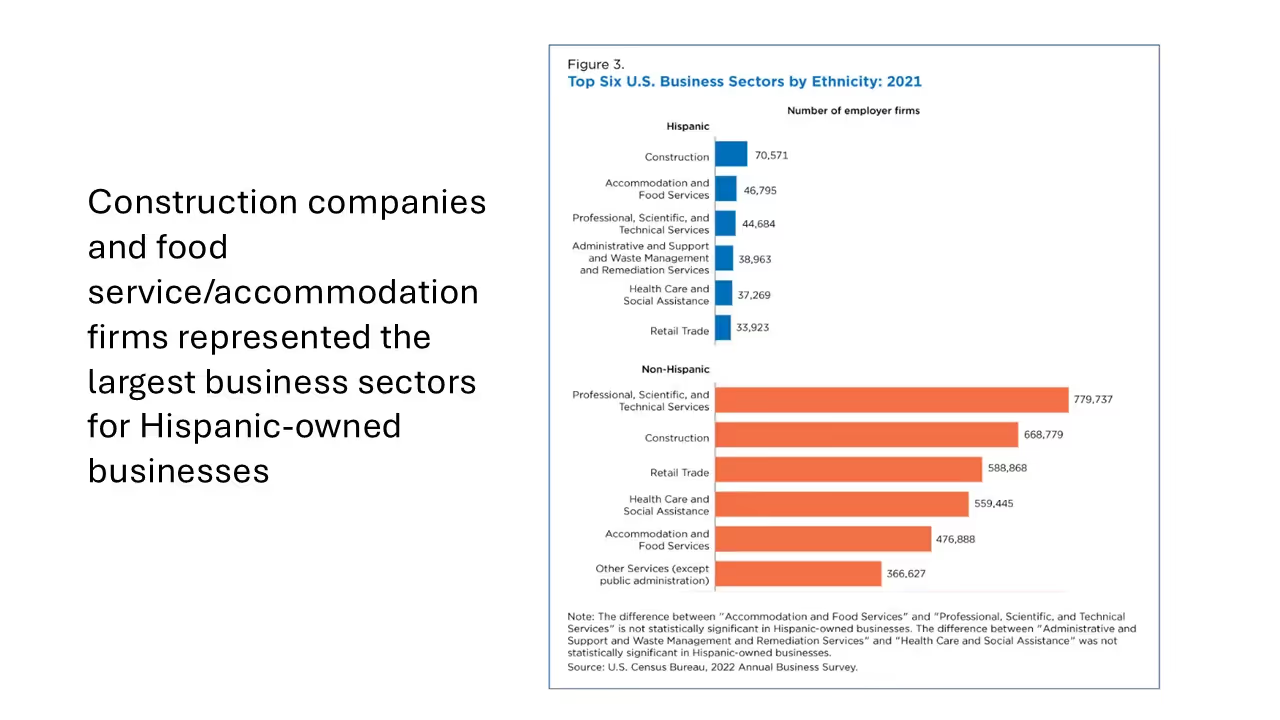

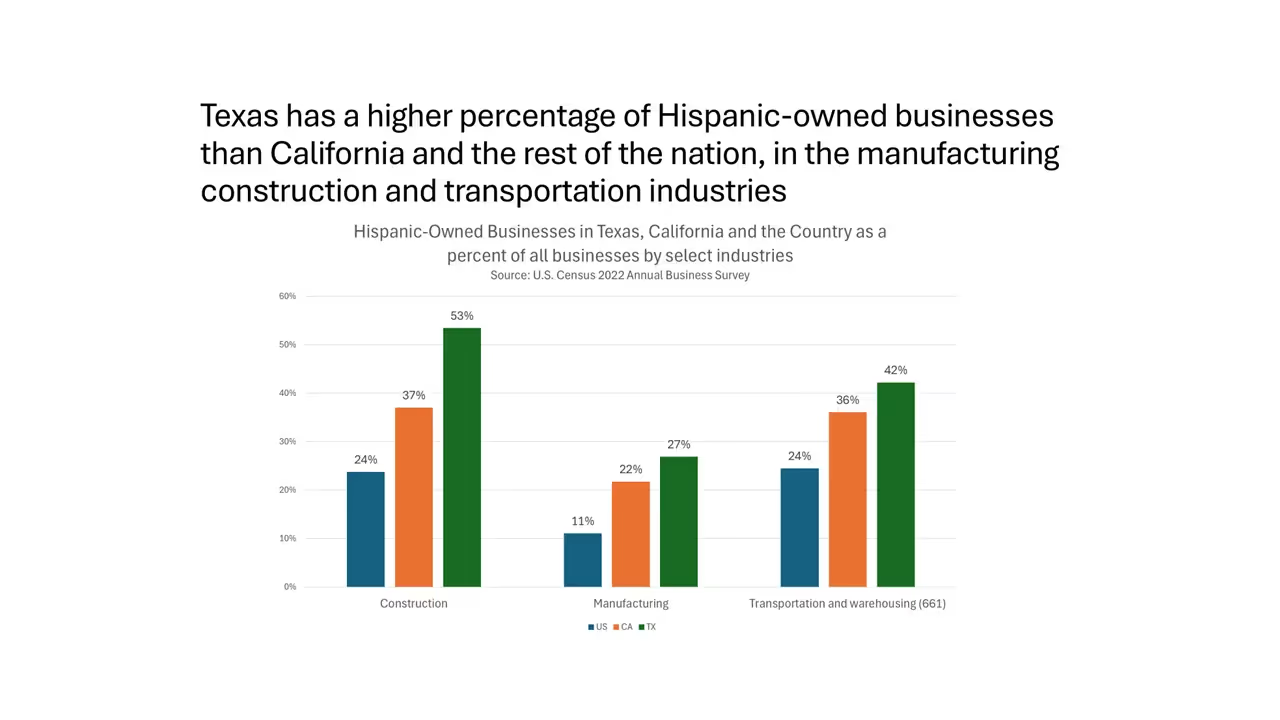

Construction companies and food service and accommodation firms are the largest business sectors for Latino-owned businesses. This concentration is clear in the three largest Latino economies: California, Texas, and Florida. Across the country, the market shares for Latino-owned businesses in these sectors already exceeds 20%, but in California, Latinos own roughly 30% of all construction, transport, and manufacturing businesses. Texas does even better, by around 5%-10%, and Latino-owned businesses account for a remarkable half of all the state’s construction firms.

Overall, Latino-owned businesses in Texas and Florida, however, represent a significantly larger percent of the total sales value than those in California or the nation as a whole. But as we saw in demographics, Latinos’ business focus has shifted increasingly to other states. The highest rates of growth have been in areas—notably in the Plains and mid-south states like Arkansas—with lower Latino concentrations.

In the coming decade, a major challenge for Latino business will be growing their employment base. A sizable proportion employs no employees or only a handful. In recent years, however, the percentage of Latino firms with employees has grown. These firm owners are less likely to be college graduates or have advanced training than other business owners, but they remain an engine for their own and their employees’ upward mobility.lxi These owners are also more oriented than their white counterparts to supplying valuable employee training.

Housing ownership is the second means of upward mobility. We have seen a strong Latino propensity to invest in achieving this key element of the American dream. A parallel aspect to understanding Latino economic progress, however, is their propensity to invest in another element of the American dream: business ownership. In this regard, Latinos have made strong progress over the past two decades.

Housing ownership has long been the fulcrum of asset accumulation particularly for middle- and working-class. One constant in both our survey and focus groups is the enormous emphasis Latinos place on homeownership. Home ownership has historically been the primary way middle-class households accumulate wealth. According to the Census Bureau, home equity accounts for roughly two-thirds of middle-income Americans’ wealth.lxii

U.S. Latinos view homeownership as a cornerstone of the American dream and a critical step toward building generational wealth. This aspiration is deeply embedded in Latino culture; many families teach children from an early age to prioritize homeownership. Unsurprisingly, Southern and Midwestern states continue to draw significant numbers of new Latino homebuyers. For the third consecutive year, Texas remains their top destination; the state has seen the highest influx of Latinos of any state in nine of the past fifteen years.lxiii

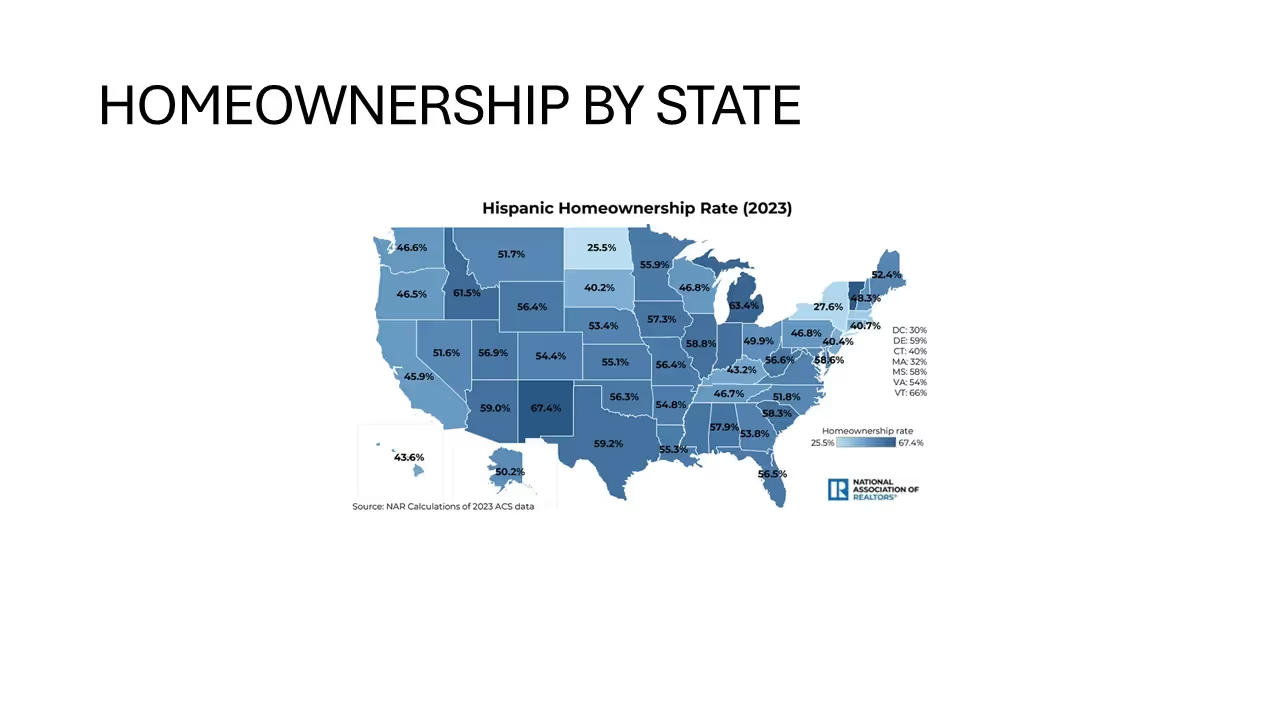

Despite headwinds that are slowing homeownership in general, Latino homeownership has steadily increased over the past three decades, rising from 42.3% in 1990 to 51.1% in 2022.lxiv In 2023, the rate reached 49.5%–51%, depending on the data source. This represented the largest increase among all racial or ethnic groups in recent years.lxv

Studies highlight that Latino communities see homeownership as essential for stability and upward mobility. Families often go to great lengths, including leveraging co-borrowers or relocating to more affordable regions, to achieve this goal.lxvi The market has amply rewarded many who have bought homes in the past. In both Texas and California, Hispanic homeowners have seen their home equity increase their wealth.

California and the other West Coast states have seen a higher level of housing price increases in the past decade than Texas and other Southern states. This gap in purchasing power, in addition to providing more income for people, has translated into a significantly higher percentage of home ownership among Latinos in Texas than in California. Overall, 59.2% of Texas’ Latino households own their own homes, while only 45.9% of Californians do. Overall rates are lowest in the Northeast but higher in both the South, notably Florida, and across the Midwest.

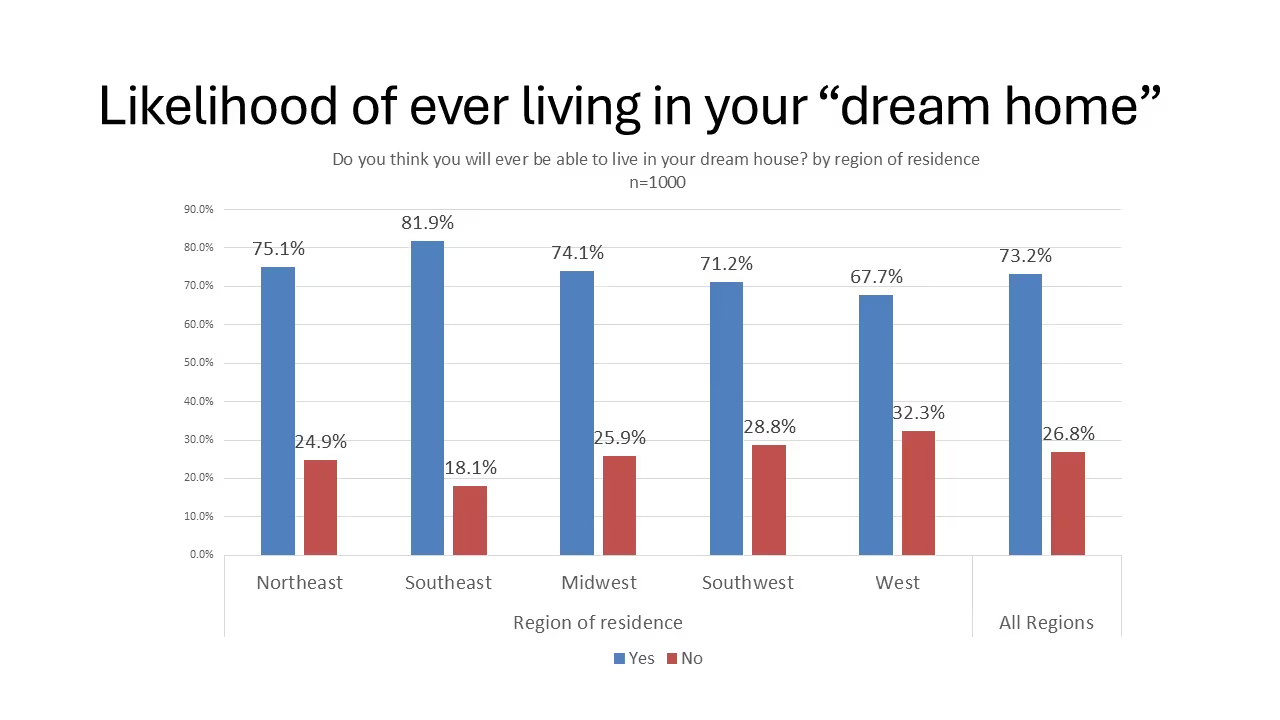

In terms of their self-perceived economic progress, more than half of those surveyed own their own home today. Most remain optimistic about moving “up the ladder” to their “dream home” in the future. Depending on where they live, between 68% and 81% of Latinos see themselves as being able to live in their “dream home” in the future.

Regional differences here are important: 81% of Latinos living in the Southeast think they will be able to own their dream home, but only 68% of those living in the West think the same. This contradicts the common assertion that these highly suburbanized, red-leaning states are hostile to Latino aspirations. Kyle Paoletta’s recent American Oasis spelled out that assertion by focusing on older barrios and the legacy of “white supremacy,” but he seems all but indifferent to the aspirations of those Latinos who now populate the region’s sprawling suburbs.

Re-industrialization brings opportunities

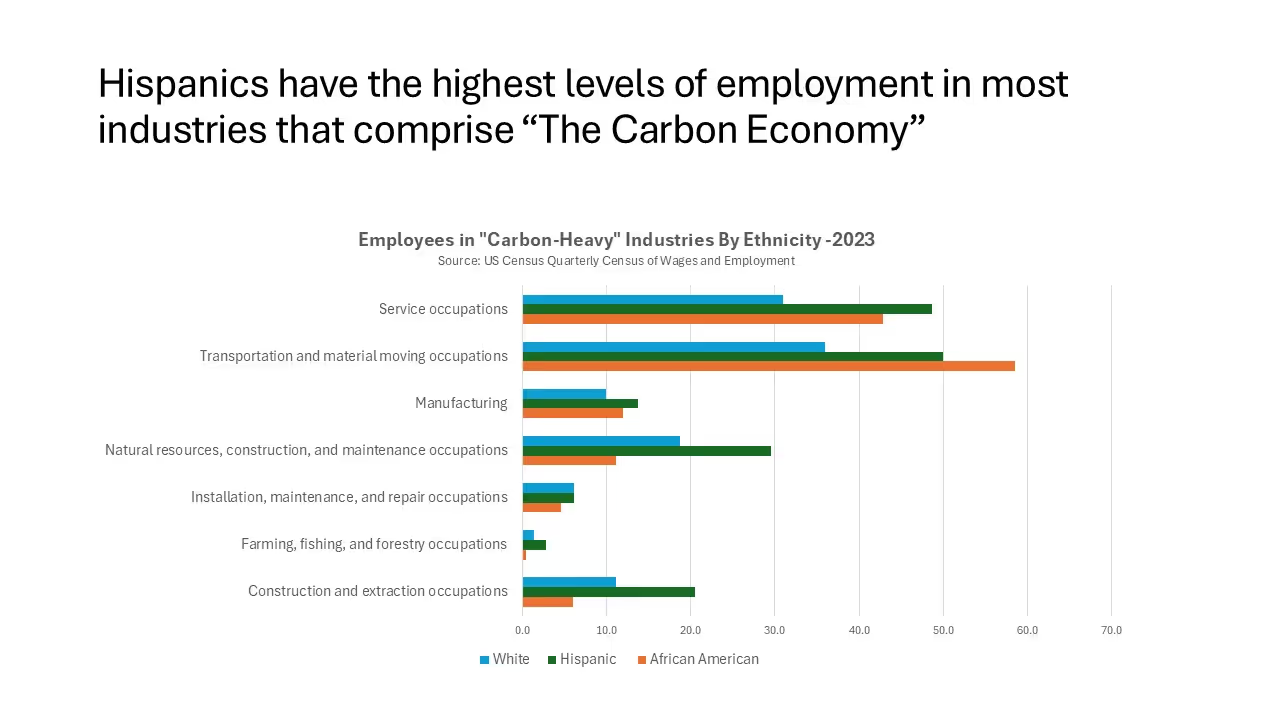

Perhaps the least recognized opportunity for Latinos, and for America in general, is their potential contribution to the U.S.’s industrial rebirth. The Latino labor force already plays a critical role in the U.S.’s agricultural, food processing, and manufacturing industries, what can be described as “the carbon economy.” The U.S. currently suffers a deficit of over 600,000 skilled manufacturing workers and a projected shortage of 2.4 million by 2028. In an era where most Western and East Asian countries face a rapidly declining workforce, Latinos and other immigrants keep the U.S. workforce growing.lxvii

A recent study by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis notes that as many as half of all Texas’ manufacturing workers and over twenty percent of all those in Illinois and Nebraska are foreign born.lxviii In old industrial metros like Toledo, immigrant workers are the only source of labor market growth in an area where population is declining.lxix Today barely 58% of all working-class Americans are white non-Hispanic; according to a 2016 Economic Policy Institute study, people of color will constitute the majority of the working class by 2032.lxx

Seizing these opportunities will require Latinos to leverage their work ethic and increase their skill levels in critical areas. By focusing on these critical skills, Latinos can complement their strong work ethic and position themselves to take advantage of new economic, technological, and entrepreneurial opportunities. This reflects our biggest long-term concern: Latino youth. Despite progress, they are still underperforming in terms of education when compared against other groups. As these young people enter the workforce, it is critical that they do not duplicate the non-engagement shown by many non-Latinos, particularly young males. An estimated 37.7% of all Americans are neither in school nor in the labor force.lxxi

Significant achievement gaps also challenge Latino youth. The National Center of Education Statistics reports that Latinos lag in both proficiency and rate of high school graduation compared against whites and Asians. Despite rising Latino enrollments, which are now close to parity with white college enrollment, college completion rates also lag. Only 16% of college enrolled Latino students earn bachelor’s degrees compared to 43% of white students and 66% of Asian students. Latinas generally do better than their male counterparts, which reflects a growing national trend.lxxii

Policies for the New America

The data paints a picture of relative economic health for U.S. Latinos. There are clear differences between states, but across the country as a whole, Latinos appear to be thriving. The relative disparity in the cost of living between California and Texas seems partially responsible for the Lone Star state’s higher growth levels. In the success metrics associated with achieving the American dream—home ownership, wealth accumulation, and business ownership—Latinos are making great progress, especially in Texas and other red states.

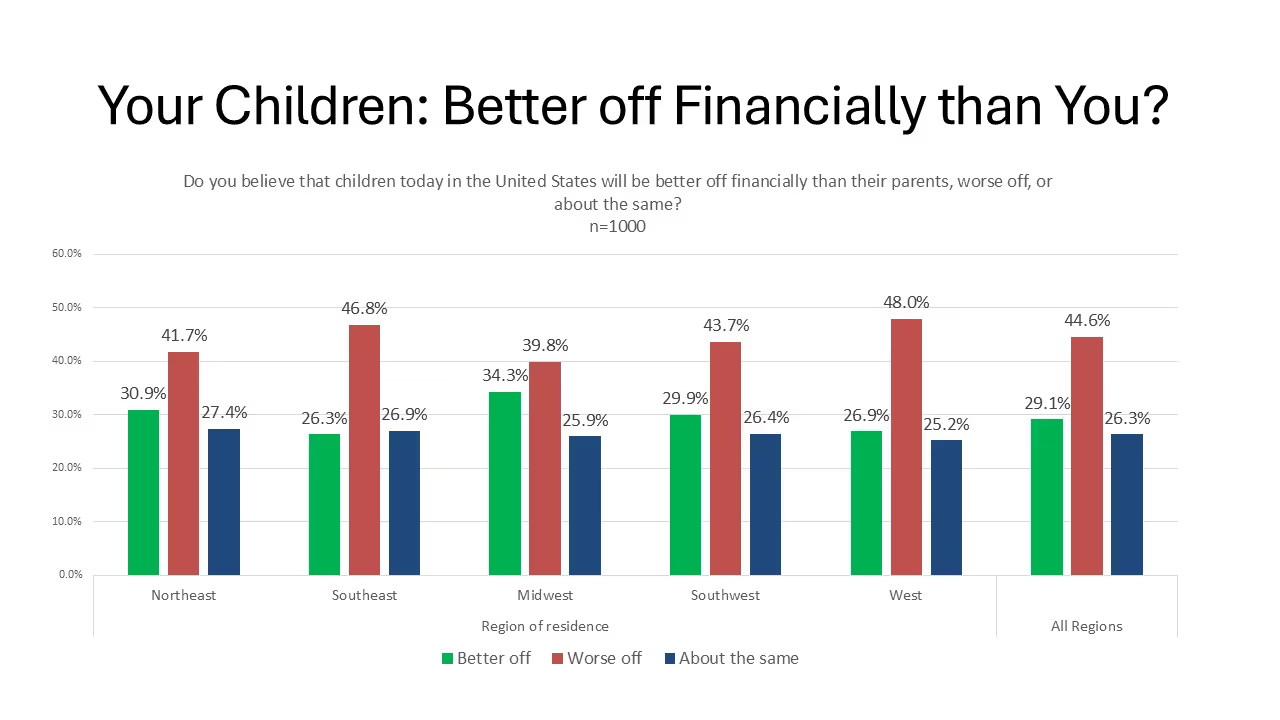

Wherever they live, however, if Latinos wish to follow the well-trod ethnic evolution, they require a growth-oriented economy. Many Latinos feel their children will not achieve the same success levels they have, but this sentiment is far less pronounced in growth oriented Southern and Southwestern states. But in that sentiment is a warning: Latino prospects are under assault, and we need policies to prevent their decline.

Demographic trends and economic evidence show that Latinos will be a growing share of future American households, children, and workforce. Latinos already play a significant role in the Southwestern states and are rapidly expanding in the U.S.’s large and smaller labor markets. A large majority (76%), according to our survey, plan to relocate to areas where they can best meet their goals, which include living in a single-family home (79%). Safety, jobs, affordability, and education are far more important to most Latinos contemplating relocation than cultural concerns, such as living with people who share their background or politics.

State and local governments’ natural incentives to attract highly mobile cohorts to raise families, participate in the economy, and pay taxes, are strong. If governments are to achieve these goals by attracting Latinos, however, they must clearly understand Latino priorities. These priorities are basic American priorities; they are not race based. Most Latinos prioritize securing a quality, middle-class life based on entrepreneurship and work, buying a home, building household wealth, and educating their children in safe neighborhoods. And like Americans of any race, they tend to settle increasingly in the suburbs.

These objectives were once American life’s unquestioned core, irrespective of political affiliation or ethnicity. But the last decades have seen the aging, wealthy beneficiaries of prior decades of American opportunity embrace, alongside their privileged progeny, issues like “environmentalism, racism, and sexism” over working to improve the nation’s largest growing ethnic group’s social mobility.lxxiii

Policies consistent with fundamental Latino goals are not just for Latinos but reflect middle-class communities’ general aspirations. An especially important concern that policymakers often overlook is the value of time for younger families who do not want to waste hours traveling to a job or trying to manage school, shopping, medical and other needs using slow, increasingly dangerous public transit.

States and localities need to align policy needs with these priorities. Homeownership and business formation rates are currently better in America’s more conservative communities—including some like Democrat-run North Carolina—because they tend to be less likely to boost energy and housing costs and more often allow people to live near where they work. These states and locales also value essential public safety, school, and other service needs than in progressive localities, particularly larger cities.

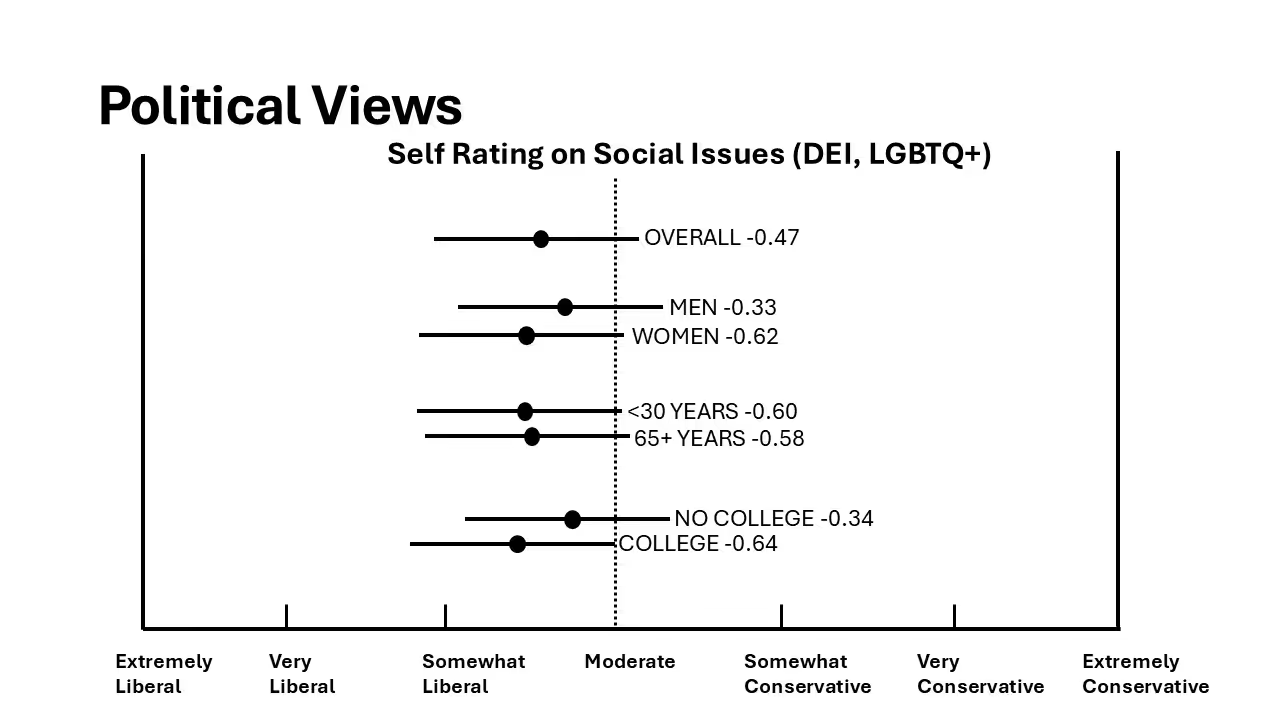

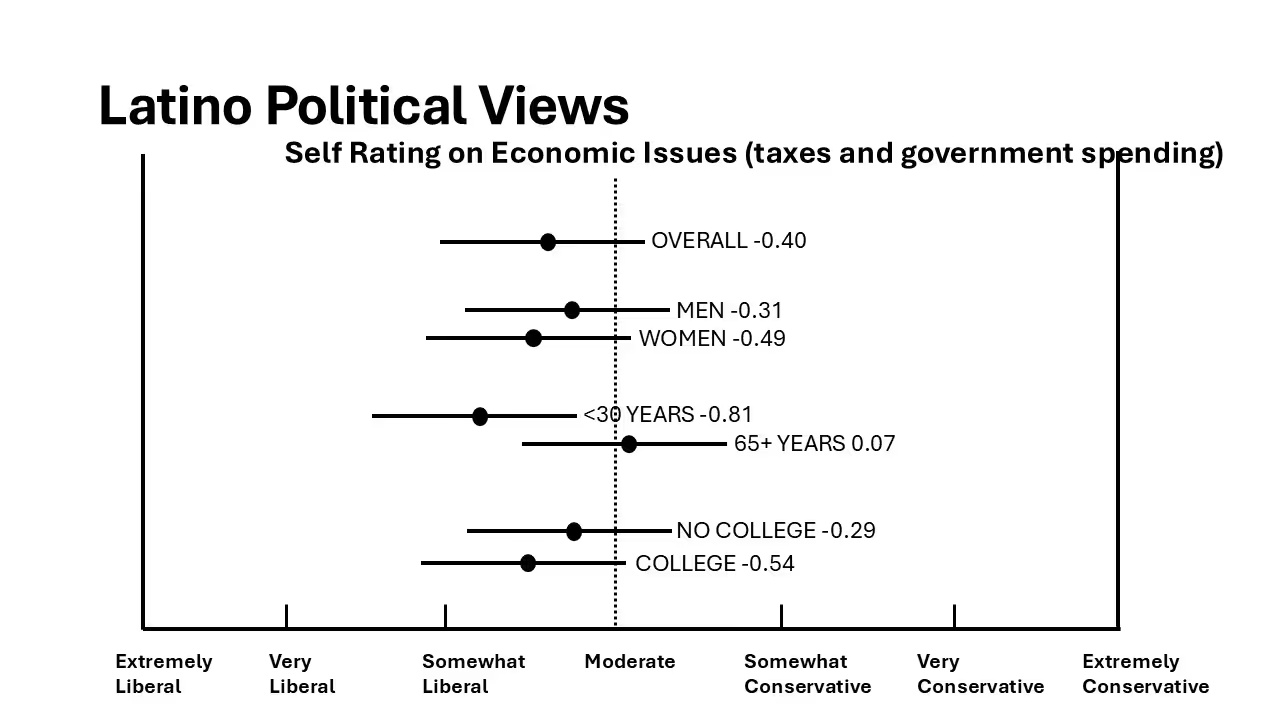

The last national election showed that American middle-class voters, including Latinos, will abandon political agendas that favor ideology over bread-and-butter issues.lxxiv Our survey showed that Latinos are politically moderate in general, with a slightly more leftist tinge, but they are open to best offers. Both red and blue states need to recognize that Latinos along with the American middle class will thrive more from focusing on the framework that sustained American success in prior eras than from ideological conflict, including the following policies.

1. Provide affordable and effective police, fire, medicine, educational, and other critical public services.

Any effective policy that benefits Latinos and the American middle class must begin by focusing on basic community safety, quality education, and other essential public services. Other efforts will fail if people do not feel safe, if the local educational system cannot produce graduates who can meet applicable language and mathematics standards, and if public utility and other services do not work well.

Our report shows that the Latino population is more optimistic generally than other Americans about the value of work and opportunities for upward mobility. They are also less likely to support police defunding and prefer that schools focus on classroom improvements over locker room ideology. Latinos are the fastest growing percentage of the nation’s active-duty military and local police departments.lxxv lxxvi The proportion of 25-29-year-old Latinos graduating from high school rose from a woeful 58.2% in 1996 to 88.5% by 2021.lxxvii From 1990-2020, Latino postsecondary educational enrollment grew from 782,000 to 3.7 million.

Latino households want to live in safe communities. National polls show that Latinos are among the least likely groups to support police force funding cuts.lxxviii Among self-described liberals, nearly 60% of Latinos oppose defunding police, far more than white liberals (27%) and Black liberals (44%).lxxix Communities that prioritize effective, efficient police, fire, and emergency medical will be more consistent with Latino and the American middle-class’s goals than those that want to “reimagine” these basic services for ideological purposes.

Similarly, as former California Senate majority leader Gloria Romero wrote, Latinos also desire, but often do not receive, quality educational services.lxxx In California, for example, Latino students account for over 56% of all public-school students, but only 36% met English language proficiency standards and just 22.7% met math proficiency standards. California students perform worse than their counterparts in Florida and Texas, and California Latinos rank among the bottom ten states higher educational degree attainment.lxxxi

Among several needed reforms, Molina suggests that California implement greater school choice programs and increase school administration accountability for student performance. These recommendations may not play well with teachers’ unions, but they are consistent with the the state’s still enormous Latino population’s needs and ambitions. If these needs go unmet, and their school children continue to fail at rates greater than those in other states, the Latino population will likely leave.

Polling data indicate that a large majority of Latino parents, in some cases as high as 85%, favor charter schools and school choice.lxxxii Recent studies show that cities with school choice programs have increased academic performance, including for lower-income students who are performing at levels closer to more affluent peers.lxxxiii

2. Build affordable single-family homes.

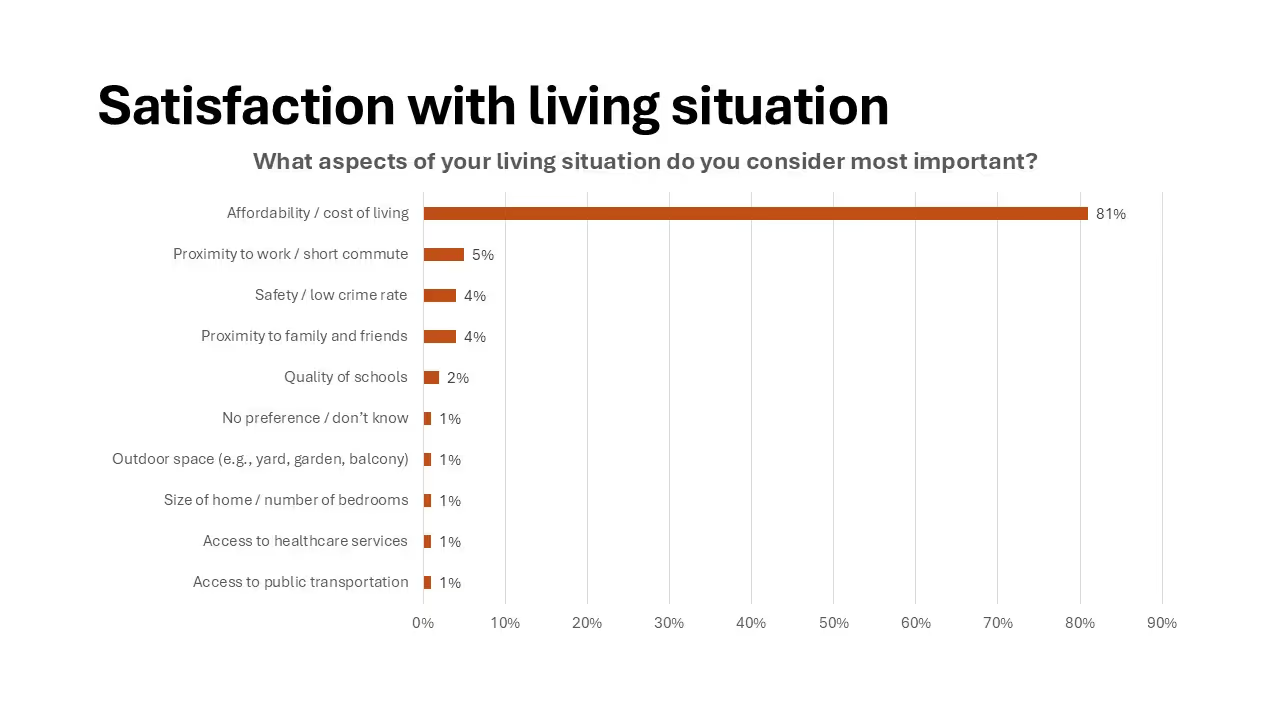

Latinos, like nearly all Americans, want to own single-family homes, in part to accommodate children, but also because homeowners have forty times the net worth of renter households.lxxxiv Housing is the largest cost of living component; our survey showed Latinos ranking it their highest concern, and most currently live in single family homes although many still rent.

In much of America, however, particularly in the Western and Northeastern states like California, Oregon, Washington, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, public policy disfavors single family homes and instead builds higher density, multifamily rental units in already urban, “infill” areas.lxxxv lxxxvi lxxxvii lxxxviii The result has been catastrophic for increasing housing supplies of any kind, let alone producing the single-family homes people most desire. Infill oriented housing policies also concentrate new development in the locations where land and building costs are most expensive. Cash-starved local governments have the most incentives to exact enormous permitting and impact fees from these locations before issuing a building permit. People do not want the housing built in these areas and it is, in any case, unaffordable for middle- and low-income households.

The top priority for ensuring that America builds affordable, desirable homes is to recognize that cities and states must allow for new land development. Despite endless concerns about suburban “sprawl,” California, the nation’s most populous state, has developed only 6% for urban uses.lxxxix A recently published analysis showed that even slightly opening America’s existing urban footprint could result in three to six times the number of new homes currently being built.xc Far from an undesirable blight, even densification advocates now concede that “sprawl” is an important strategy for producing affordable housing in a form people desire.xci

Americans in general and Latinos specifically are eagerly populating the country’s expanding suburbs and emerging communities in rural regions. According to Brookings, the nation’s suburban populations added more new residents than primary cities from 2010 to 2020. Latinos accounted for the largest amount of net new U.S. suburban population growth, including around the Chicago and Houston metropolitan regions.xcii xciii xciv A U.S. Senate study recently showed that America’s rural areas also experienced the largest Latino population growth in the nation from 2010-2020.xcv

Land, construction, and permitting costs have risen to particularly unaffordable levels in the locations most committed to infill development where land is most costly and even very small rental units are unaffordable for most residents.xcvi Moderating these costs is also crucial.xcvii There is a clear link between higher regulation affecting land use, labor and permitting fees, and housing costs.

According to a 2025 RAND analysis, housing development costs were highest in California, which has one of the nation’s most comprehensive infill-only housing policies, and where regulations require significantly higher labor expenses for larger urban projects. Communities there can exact over $100,000 per unit in permit and environmental impact mitigation fees.xcviii Housing construction costs were next highest in Colorado, a once “red,” affordable state, that is increasingly implementing a more restrictive land use and development approval approach. Affordability, our survey found, has become the biggest issue by far for Latinos.

Housing was least expensive to develop in Texas, where land use, building code, and permitting costs facilitate rather than impede development.xcix It is simply impossible for places like California, and in areas adopting similar policies like Colorado or Washington, to meet Latino and other middle-class Americans’ housing priorities when even a supposedly “affordable” apartment costs over $1 million to build.c The clear result: Latino home ownership rates are highest in states that encourage home building such as Texas and Florida.

Absent unambiguous efforts to increase housing construction and lower regulatory barriers, no amount of government encouragement, or even top-down mandates, is likely to be successful. Despite decades of legislation, subsidies, and regulatory “streamlining,” housing supplies have chronically failed to meet demand and have become even less affordable in highly restrictive, pro-infill places like California, Portland (OR), and Seattle.ci cii

This clearly has not worked. California created a regional housing needs quota system that supposedly requires each city and county to plan for what state bureaucrats determine is the amount of new housing needed to meet several years of demand for households ranging from the most affluent to the very poor.ciii The program is a dismal failure and most notably did not produce even a fraction of the mandated new homes for moderate- and low-income residents. In February 2025, for example, Los Angeles county reported that 37.5% through the current state regional housing needs “cycle,” it had only permitted—let alone actually built—6,135 of the 90,052 units state agencies require, and just 952 of the 53,519 (1.77%) of the county’s mandated moderate- to low-income units. civ

Unsurprisingly, as we see above, Latino homeownership rates are much higher in states with large historical Latino populations like Texas and the Southeast that have less restrictive land use constraints, allow for urban expansion, and have lower labor and permitting costs. But Latinos are also increasingly drawn to smaller suburban and rural communities that offer even greater affordability, employment opportunities, and a better quality of life.

By preventing wealth accumulation through homeownership, making existing communities unaffordable, and generating high-cost rentals, America’s constricted housing states and communities are preventing middle class Latinos from improving their lives. They are also, as this report discusses, reducing opportunities for very poor residents, which in several states include large Latino populations, to escape poverty.

3. Repeal performative climate slogans and failed climate policies that hurt working families and have negligible or negative climate consequences.

Climate and energy extremism lead to economically regressive public policies that reduce energy reliability and increase household, business, and transportation costs that disproportionately harm less affluent Latino and middle-class households.cv cvi Sectors like manufacturing, logistics, energy and natural resources, and construction that exist in the real world, not cyberspace, are a crucial employment base for Latino and aspiring middle class households.

As this report discusses, these sectors include industries that use machinery, require energy, and ship materials and products to other producers and end users. Latinos comprise a large proportion of American construction, manufacturing, transportation and moving, installation, maintenance and repair, extraction, natural resource, and food industries.

As we have seen Latino-owned businesses are particularly prevalent in the construction, accommodation and food service, and waste and remediation management sectors as well as professional services, health care, and retail trade. The keyboard economy is contracting, and the pace of that contraction is expected to accelerate due to AI’s rise.cvii Today, however, there is growing interest in high paying alternatives in fields like manufacturing, logistics, and construction business that require workers to be physically present and mobile to provide in-person services, make and convey goods, and collect, process, and distribute food and materials used by other households and employers. These are professions where the Latino presence is particularly strong.

States and regions that allow climate advocacy to overwhelm sensible energy and industrial regulation have high and increasing energy prices and discourage sectors important to Latino workers. From 2008-2023, as California bureaucrats began their push for “climate neutrality,” state energy costs rose by 53%, five times the U.S. average increase of 9.6%.cviii The state’s powerful climate lobby secured massive solar, electric vehicle, battery, and other public subsidies that even sympathetic agencies now admit perversely transfer wealth from the poor to the rich.cix

In some cases, climate obsession pushes state leaders to pursue the complete elimination of industries like oil and gas production, which sustain hundreds of thousands of well-paid jobs in places like California, where Latinos make up 43.6% and the largest share of the state’s workforce.cx cxi

States that prioritize climate issues take less interest in, and will actively oppose, national efforts to protect tangible economy jobs from being lost to overseas locations. Simultaneous with its efforts to end oil and gas production from its own abundant reserves, California, for example, imported $361 billion of foreign crude oil from high emission suppliers like Saudi Arabia. cxii cxiii From 2009-2024, California ran an astounding $3.9 trillion goods and manufacturing trade deficit, including about $1.9 trillion with China alone, the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, and close to 30% of the nation’s total deficit. cxiv cxv Despite a desperate need for quality working- and middle-class employment, California was among the most vigorous opponents of the Biden Administration’s Chinese tariffs, it begged China not to curtail exports to the state and was the first to file a lawsuit against the Trump administration’s Chinese tariffs. cxvi cxvii cxviii cxix

The Latino population is younger, more motivated to join the workforce, and willing to move to more promising economic opportunities. More moderate energy policies with historically large Latino populations are attracting upwardly mobile Latino households. But rapid Latino population growth is also occurring in new parts of the country, such as Pittsburg, Cincinnati, Columbus, and Louisville where maintaining energy affordability is a priority. Industrial growth is desirable and decades of economic setbacks due to globalization have made leaders more cautious about pursuing strategies like supposedly “net zero” local emissions with enormous import volumes from heavily polluting suppliers.

4. End the war on cars and respect the need for time-saving transportation.

Latinos have flourished in states and communities where transportation costs, including vehicles and fuels, are reasonably priced and roadways are accessible and maintained. They have done worse, suffer a higher poverty rate, have lower real wages, and are less able to own a home in locations that impede personal vehicular use and undervalue the enormous loss of irreplaceable personal time crowded roadways and long commutes cause.

There is convincing evidence that access to a personal vehicle is one of the most crucial factors associated with improving the lives of poorer and middle-class worker households.cxx Over a decade ago, the Urban Institute documented the importance of “driving to opportunity”: a family’s ability to minimize travel time and maximize mobility for work and transportation. People with vehicle access found better housing, better jobs, and could far more easily manage a family, including shopping, school, sports, and other activities, by using a car or light truck than those without personal vehicle limited to public transit.cxxi

A vehicle is also a widely embraced symbol of freedom and accomplishment. As Arizona Senator Ruben Gallego famously explained to disheartened post-election Democrats: "Every Latino man wants a big-ass truck. There's nothing wrong with that. You get your troca, start your own job, and you're going to become rich, right? These are the conversations we should be having.”cxxii

Yet many states, including California, Colorado, Oregon, Minnesota, and Connecticut, are attempting to decrease personal vehicle use.cxxiii cxxiv In California, for example, state bureaucrats decreed that Californians must reduce per capita vehicle miles travelled (V.M.T.) by 30%, which is about two and half times the temporary decline the pandemic caused.cxxv These mandates apply to both existing and future residents and workers, and the state will not approve new businesses unless they comply with the regulation or pay what can be exorbitant fees to “mitigate” for supposed V.M.T. impacts. V.M.T. regulatory costs can be astonishingly expensive. In July 2025, after the U.S. Supreme Court held that regulators did not sufficiently justify a $24,300 V.M.T. mitigation fee they imposed on a private landowner seeking to building a single house, a state court reimposed every penny of the exaction in full.cxxvi

Like the state’s failing regional housing development quotas, these intrusive, costly personal mobility restrictions have been utterly ineffective. During 2019-2022, the number of commute trips working from home offset rose from 7.6% to 19.3%. Yet, per capita V.M.T. increased by over 15% from the pandemic level and is trending up. Heedless of these realities, state leaders still want to “reimagine” roadways to “support people over cars,” which in practice means not building new roads, taking away badly-needed existing capacity for seldom-used bike and bus lanes, taxing every mile people drive, and doubling local transit by 2030, even though transit fell to just 0.9% of all commute trips in 2022.cxxvii cxxviii cxxix

Crippling vehicle use is especially harmful to sectors in which most Latinos work, which require frequent movement to different jobsites, resource extraction, and food harvest locations, and providing in-person services at homes, hospitals, or multiple businesses. On average, Americans commuters spend about twenty-eight minutes in a car commuting versus forty-seven to forty-eight minutes traveling by subway, light rail, or trollies.cxxx After hundreds of billions worth of spending and countless regulations trying to make California transit-friendly, an average commute takes 28.2 minutes with a personal vehicle and 47.6 minutes using transit.cxxxi Compounded by misguided state housing programs that force Latinos ever farther from urban job centers to find affordable homes, these polices disrespect and ignore their basic desire to conserve time for family and personal goals rather than waste their lives in traffic jams.cxxxii

Succeeding in the Latino future

We should not cast policies that address U.S. Latino priorities as a red/blue conflict. These policies should reflect widespread American values and ambitions. Localities that promote affordable housing, energy, and services, and allow for a full spectrum economy will attract an increasingly larger share of the nation’s fastest growing and hard-working Latino cohort. Latinos, this report shows, are more than willing to “vote with their feet” and relocate to less expensive, often peripheral, and even rural areas to obtain the housing, employment, and time with their families that they prioritize.

This is particularly relevant in states like California or Texas, where Latinos have heavily settled and that represent a huge part of the economy. As Latinos disperse, this will become ever more the case in most of the country. Policymakers that align their program with this vital segment’s priorities will likely prevail in the battle for talent and capital. Those who do not will lose this population and, in effect, erode their future influence.

Latinos are America

Until the 2024 general election, many political leaders embraced the idea that the Latino community had linked itself fundamentally to the Democrats and would remain linked to them indefinitely. But it was the Democrats whose inability to recognize this basic reality caused them to suffer the most in the last national election, which saw Latino males especially give Trump a huge boost.cxxxiii In a particularly shocking development, Trump won 97% Latino Starr County in south Texas.cxxxiv

Policymakers that align their program with the priorities of this vital segment will likely prevail in the battle for talent and capital while others will lose this population. In effect, they will also erode their future influence. After all, this growing population and workforce, particularly if engaged, represents the country’s fundamental advantage against its primary East Asian and European competitors, all of whom are either already depopulating or well on the road to it.cxxxv

In this competition, Latinos represent America’s secret weapon. Some of this awaits some form of immigration reform, which would allow law-abiding, long term undocumented to find a secure path to citizenship or legal residence. This is not just an issue for Latinos, but critical if we want to see them invest more in America through home purchases, new business creation, and starting families.

Yet the primary issue for most Latinos is not immigration; the vast majority of them are now native born and proficient English speakers.cxxxvi They are deeply entrenched in communities, and, as the report suggests, their presence and influence are spreading beyond the Southwest and the urban barrios into suburbs, exurbs, and small towns across America.

They are not a separate people, whose interests revolve around la raza and needing policies that represent racial redress, but simply another face of America. They are part of that remarkable and evolving “race of races,” as Whitman put it, that has been America’s existential reality.cxxxvii There is only one America; it is perhaps a little browner and less European than it used to be, but still capable of employing its diversity to make it remarkable.

Books & Scholarly Sources

McLemore, S. Dale, and Ricardo Romo. The Origins and Development of the Mexican American People, in The Mexican American Experience: An Interdisciplinary Anthology, ed. Rodolfo O. de la Garza et al. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985.

Steiner, Stan. La Raza: The Mexican Americans. New York: Harper & Row, 1970.

De León, Arnoldo. Ethnicity in the Sunbelt: Mexican Americans in Houston. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2001.

Frey, William H. The Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2018.

Reports & Data Sources

U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey (2018–2022). https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Market Information for the State of California. https://labormarketinfo.edd.ca.gov/specialreports/CA_Employment_Summary_Table.pdf

Migration Policy Institute. “Poverty Declines Among Immigrants.” (2023). https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/mpi-poverty-declines-immigrants-2023_final.pdf

UnidosUS. Latino Education Report 2022. https://unidosus.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/UnidosUS_Latino-Education_2022.pdf

News & Commentary

Mejia, Brittny, et al. “In an increasingly optimistic era, immigrants espouse a hallmark American trait.” Los Angeles Times, September 17, 2023. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2023-09-17/immigration-poll-american-immigrants-more-optimistic

Contreras, Russell. “Exclusive poll: Most Latinos believe in the American Dream.” Axios, March 24, 2022. https://www.axios.com/2022/03/24/axios-ipsos-poll-american-dream-latinos-politics

Hayes-Bautista, David E. El Cinco de Mayo: An American Tradition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012.

Berman, Russell. “As White Americans Give Up on the American Dream, Blacks and Latinos Embrace It.” The Atlantic, September 4, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/09/the-surprising-optimism-of-african-americans-and-latinos/401054/

Research & Policy Analysis

McKinsey & Company. The Economic State of Latinos in America: The American Dream Deferred. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/sustainable-inclusive-growth/the-economic-state-of-latinos-in-america-theamerican-dream-deferred

Brookings Institution. “Rethinking Homeownership Incentives.” https://www.brookings.edu/articles/rethinking-homeownership-incentives-to-improve-household-financial-security-and-shrink-the-racial-wealth-gap

Economic Policy Institute. “Changing Demographics of America’s Working Class.” https://www.epi.org/publication/the-changing-demographics-of-americas-working-class/

Statistical & Academic Journals

SpringerLink. “U.S. Latino Poverty and Child Outcomes.” https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11113-025-09964-0

Economic Synopses, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/economic-synopses-6715

Web Articles & Resources

Hampton Think. “The Colonial Roots and Legacy of the Latinx/Hispanic Labels.” https://www.hamptonthink.org/read/the-colonial-roots-and-legacy-of-the-latinxhispanic-labels-a-historical-analysis

Fox News. “Salsa Outsells Ketchup as American Tastes Change.” https://www.foxnews.com/food-drink/salsa-outsells-ketchup-as-american-tastes-change

Pew Research Center. “Hispanic Enrollment Reaches New High at Four-Year Colleges.” https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/10/07/hispanic-enrollment-reaches-new-high-at-four-year-colleges-in-the-u-s-but-affordability-remains-an-obstacle/

Pursuit of Happiness

Revival: Americans Heading Back to the Hinterlands

Smaller communities throughout the country are poised to play an outsize role in forging our future.

Exodus: Affordability Crisis Sends Americans Packing From Big Cities

The first in a two-part series about the Great Dispersion of Americans across the country.

.jpg)

The False Equivalence of Multicultural Day

Parents have an affirmative obligation to reinforce patriotic values and counter the narratives that are taught in school.

Norman Podhoretz: American Patriot, Faithful Jew, and Indomitable Defender of Civilization

Podhoretz never turned on the promise of America.