Trump's Jeffersonian Foreign Policy

The constitutional framework for presidential war powers traces back to the earliest days of the Republic, and no president did more to establish its foundations than Thomas Jefferson’s war against the Barbary States.

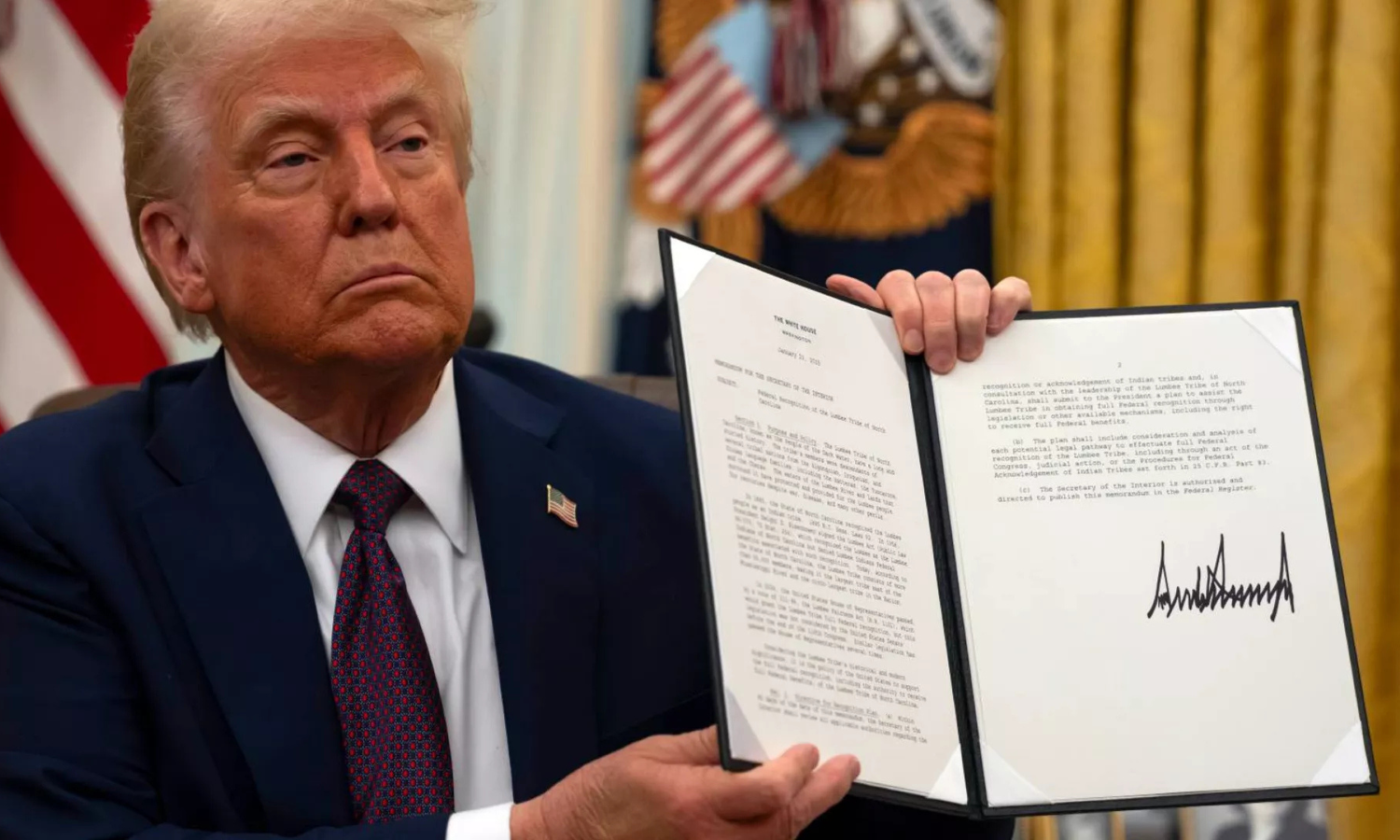

A President orders American forces to attack a hostile foreign regime without prior congressional authorization. He authorizes covert action to overthrow the regime’s ruler. He funds these operations in secret and notifies Congress only after the mission succeeds. When the smoke clears, Congress does not challenge the intervention either by cutting off funds, passing a statute, or impeaching the President. This scenario describes the Trump administration’s ongoing conflict with Venezuela. The United States is fighting a war in all but name against the regime in Caracas. The United States has imposed a blockade on Venezuela’s oil exports, closed its airspace, sunk alleged drug-running boats leaving its ports, and, of course, launched a snatch-and-grab operation of its head of state, Nicolas Maduro. Not only did the American armed forces capture Maduro and return him to the United States for trial, but it also destroyed Venezuela’s air defenses and killed the security detail guarding him. The Trump administration is now engaged in a slow campaign of regime change that has it negotiating with Maduro’s successor, Delcy Rodriguez, but also hosting the leader of the opposition, Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Corina Machado.

But this scenario also describes President Thomas Jefferson’s campaign against the Barbary States. In that operation, President Jefferson ordered the U.S. Navy to attack principalities of the Ottoman Empire and then launched our nation’s first significant covert action to overthrow their leaders – all without explicit congressional approval. Two centuries later, President Trump has followed the same playbook in Operation Absolute Resolve to capture Maduro. But while Jefferson’s actions prompted only constitutional silence and congressional acquiescence, Trump’s have encountered accusations that he has violated both the Constitution and international law. Trump’s critics today would do well to learn from the example of Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, founder of the Democratic Party, and leading critic of government power. Indeed, Jefferson might well have applauded Trump’s campaign in Venezuela.

Critics of the Venezuela operation argue that the president violated the Constitution by launching a military attack without a congressional declaration of war. They claim that the President can only resort to war unilaterally when acting in national self-defense, but that he needs congressional consent to launch an offensive attack. It is not obvious that this is a meaningful distinction. The United States can often claim a self-defense rationale, as it did not only in the Afghanistan war (legitimately after the 9/11 attacks), but also in the 2003 Iraq invasion, as well as the closest parallel to the Venezuela attack: the 1989 invasion of Panama to topple the dictatorship of Manuel Noriega. In its litigation justifying the expulsion of Venezuelan nationals under the Alien Enemies Act, the Trump Justice Department argues that the United States is acting in self-defense against Venezuelan drug cartels that are harming Americans. Secretary of State Marco Rubio last week testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that the Cartel del los Soles, allegedly headed by Maduro, “flooded the United States with drugs” and “turned [Venezuela] into a base for an international criminal enterprise.”

But critics make the more fundamental mistake of ignoring the historical record that any distinction between defensive and offensive war is meaningless. Since Jefferson, Presidents have used force on their own initiative to protect American national security and foreign policy interests. The Constitution limits Congress’s role to the power of the purse, the raising of armies, and impeachment. The constitutional framework for presidential war powers traces back to the earliest days of the Republic, and no president did more to establish its foundations than Jefferson’s war against the Barbary States.

Although history remembers the Barbary States as pirates, they were in fact autonomous regions – Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis – within the Ottoman Empire, along with the independent nation of Morocco. Their leaders attacked the shipping of other nations, seized cargoes and ships, and sold captured sailors into slavery. Under the Continental Congress and the new Republic of the Constitution, the United States had paid bribes in the form of tribute (amounting to $10 million under Washington and Adams) to the Barbary nations to allow American shipping to proceed unhindered.

Jefferson rejected appeasement. When he became president in 1801, demands for higher payments and insults to American vessels convinced him to act. At a meeting on May 15, 1801, meeting, the cabinet unanimously agreed that Jefferson should send a squadron to the Mediterranean as a show of force. No one in the cabinet, including Secretary of State James Madison and Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin, believed that Jefferson needed congressional permission to order the mission. This is the same James Madison who attacked President George Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation as “an absurdity – in practice a tyranny” and claimed that the Constitution deprived the President of the power to decide on war because “war is in fact the true nurse of executive aggrandizement.”

But once Jefferson and his advisors became responsible for national security, their attitude toward presidential power changed dramatically. Confronted by the depredations of the Barbary princes on American commerce, Jefferson’s cabinet agreed that the president had the constitutional authority to order offensive military operations, should a state of war already be in existence because of the hostile acts of the Barbary powers. “The [executive] cannot put us in a state of war,” Gallatin said, “but if we be put into that state either by the decree of Congress or of the other nation, the command & direction of the public force then belongs to the [executive].” Jefferson and his advisors clearly believed that the Constitution required Congress to declare war before undertaking purely offensive operations against a nation with which the United States was at peace. The only legislative action that Jefferson could call upon was a statute enacted on the last day of the Adams administration, requiring that at least six existing frigates (American frigates at this time were the best in the world) be kept in “constant service” — an effort to prevent Jefferson from reducing the navy to zero. Jefferson and his cabinet thought that the statute could be read to allow the President to send a “training mission” to the Mediterranean. Ultimately, Jefferson and his advisors assumed they had the authority for the expedition simply by virtue of Congress’s creation of the naval forces that made it possible.

Instead of waging a defensive war, Jefferson sent U.S. naval units to the Mediterranean to attack the Barbary Pirates. Jefferson was clear about this in his orders to the naval commanders. The Secretary of the Navy ordered Commodore Richard Dale to proceed to the Mediterranean and, if he found that any of the Barbary States had declared war on the United States, to “chastise their insolence” by “sinking, burning or destroying their ships & Vessels wherever you shall find them.” Dale could impose a blockade, which he did to Tripoli, and take prisoners. Dale’s orders went well beyond simply protecting American shipping from attack. When the 12-gun schooner Enterprise encountered a Tripolitan corsair in August 1801, it fought for three hours, killed half the enemy crew, and captured the enemy vessel. The action received broad approval nationwide, and Congress passed a joint resolution applauding the crew.

Jefferson’s public message to Congress in December 1801 differed from his private orders. He suggested the Enterprise had acted only in self-defense, when, in fact, its commander had launched an offensive attack under orders to sink or destroy enemy vessels. But during the subsequent congressional debates, no one questioned the constitutionality of Jefferson’s orders to the Mediterranean squadron, and several congressmen argued that the President had the power to begin offensive operations because of the existing state of war. Congress ultimately chose to delegate broad powers to Jefferson to take whatever military measures he deemed necessary as long as the war with Tripoli continued.

Alexander Hamilton agreed with Jefferson. According to Hamilton, no congressional permission to use force was necessary once a state of war already existed:

[W]hen a foreign nation declares, or openly and avowedly makes war upon the United States, they are then by the very fact, already at war, and any declaration on the part of Congress is nugatory: it is at least unnecessary.

Hamilton was right as a matter of international law at the time, and most agree he was correct about the Constitution. Presidents should not have to wait to seek authorization from Congress when another nation has already attacked or declared war upon the United States.

Jefferson’s quest to end the Barbary threat produced another form of warfare: covert action. Shortly after the dispatch of the squadron to the Mediterranean, the American consul at Tripoli suggested that the Jefferson administration aid the brother of the ruling Pasha to overthrow the government. In August 1802, Madison authorized American naval and diplomatic personnel to cooperate with the brother, and in May 1804, the cabinet voted to provide him with $20,000. The American consul at Tunis provided another $10,000, helped the pretender to the throne to assemble a makeshift, mercenary army, and ordered the Navy to covertly transport him to Tripolitan territory. This force succeeded in capturing one of Tripoli’s major cities in 1805, forced a peace treaty with the U.S., granted U.S. trade and shipping privileges, and ended the war.

While Jefferson’s actions fell within Congress’s broad authorization to “cause to be done all such other acts of precaution or hostility as the state of war will justify, and may, in [the President’s] opinion, require,” the President chose not to inform Congress of these secret measures until six months after the peace treaty was signed. No one objected to the constitutionality of the President’s actions, and Congress even bestowed on the brother a tidy sum for his cooperation. Jefferson set the precedent for future covert action, taken without specific legislative approval, against threats to national security. Congress’s main check remained the power of the purse.

President Trump’s capture of Maduro follows directly in this Jeffersonian tradition. Like Jefferson, Trump ordered American forces into action against another nation without prior congressional authorization. In the defense of its use of the Alien Enemies Act against Venezuelan aliens in the United States, the Trump Justice Department is arguing that the Maduro government has used drug cartels to attack the United States and harm Americans. Like Jefferson, he achieved regime change through overt military action and covert operations. And like Jefferson, he will seek congressional ratification through appropriations to support Venezuela’s reconstruction and new government. If Jefferson could claim that the Barbary attacks on American commercial shipping constituted sufficient grounds for it to launch offensive naval and covert operations, the Trump administration could similarly claim that the harm to Americans from Venezuela’s government-sponsored drug cartels justified the attack on Caracas.

But this is more a matter of policy than law. The Constitution does not require Presidents to receive congressional consent for offensive hostilities. Critics who claim the Venezuela attack violates the Constitution misunderstand the function performed by a declaration of war. At the time of the Constitution’s adoption, a declaration of war was not required to initiate hostilities. Declarations defined the legal status of hostilities under international law. They did not give Congress the sole key to launch military force. Instead, the Framers decided that the president would play the leading role. “The direction of war implies the direction of the common strength,” Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 74, “and the power of directing and employing the common strength forms a usual and essential part in the definition of the executive authority.” Hamilton argued that the president should manage war because he could act with “decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch.”

Instead of demanding a legalistic process to initiate war, the Framers left the decision to wage war to politics. They granted war powers to both the president and Congress, allowing them to either cooperate or contest for primacy over war policy. The Constitution creates a presidency that can respond forcefully to prevent serious threats to our national security. Presidents can take the initiative, and Congress can use its funding power to check them. If presidents lead the nation into disastrous mistakes, Congress can impeach them, and the people can reject them at the ballot box. That was true in Jefferson's time, and it remains true in Trump's time.

John Yoo is a senior research fellow at the Civitas Institute and a distinguished visiting professor at the School of Civic Leadership at the University of Texas at Austin.

Constitutionalism

Amicus Brief: Hon. William P. Barr and Hon. Michael B. Mukasey in Support of Petitioners

Former AGs Barr and Mukasey Cite Civitas in a SCOTUS Brief

Rational Judicial Review: Constitutions as Power-sharing Agreements, Secession, and the Problem of Dred Scott

Judicial review and originalism serve as valuable commitment mechanisms to enforce future compliance with a political bargain.

Supreme Court showdown exposes shaky case against birthright citizenship

Supreme Court will hear challenges to Trump's order ending birthright citizenship, testing the 14th Amendment's guarantee for babies born in America.

.avif)

.avif)