Defending Technological Dynamism & the Freedom to Innovate in the Age of AI

Human flourishing, economic growth, and geopolitical resilience requires innovation—especially in artificial intelligence.

This paper is part of the Civitas Institute's Dynamism Outlook white paper series. Click here to download it as a PDF.

Executive Summary

In Defending Technological Dynamism & the Freedom to Innovate in the Age of AI, Adam Thierer argues that human flourishing, economic growth, and geopolitical resilience requires innovation—especially in artificial intelligence. Overzealous regulation threatens to undermine this progress. If policymakers adopt a governance philosophy of permissionless innovation over the precautionary principle, however, they can foster an environment that tolerates and protects creativity, experimentation, and risk-taking.

Important Points

Economic Growth at Risk: Over-regulation of AI limits its potential to drive innovation across industries, thereby threatening economic prosperity.

Health and Welfare Effects: Restrictive policies could hinder AI-driven breakthroughs in medicine, agriculture, and safety, reducing quality of life.

Suppressed Learning and Speech: Regulations threaten to curb AI’s development as a tool for knowledge, discovery, and expression.

National Security Concerns: Overregulation weakens the U.S.’s competitive edge against authoritarian models like China’s, endangering global liberal values.

Regulatory Inertia: Entrenched interests and a precautionary mindset favor stability over progress. This stifles innovation.

Governance Philosophy: Permissionless innovation, unlike the precautionary principle, encourages experimentation with minimal bureaucratic interference.

Proven Success: The U.S. digital economy’s growth under light-touch regulation contrasts with Europe’s stagnation under stricter frameworks.

Policy Recommendations: Thierer advocates for regulatory humility, simple adaptive rules, and protecting freedoms to innovate, code, learn, and speak using AI.

Thierer urges policymakers to reject fear-driven, restrictive AI governance in favor of a framework that champions creativity and experimentation. Embracing permissionless innovation is not only a practical necessity but a moral imperative to ensure technological progress drives human flourishing and global resilience.

Introduction

One of the strange ironies of our current moment in American politics involves the intensifying debate over technological progress.

On one hand, there is growing consensus that America needs to start “building again” by embracing a pro-growth “abundance agenda” that removes obstacles to investment and innovation.[1] Pundits of varying political stripes are thinking hard about how to make more and better things available to more people in more places across the nation.[2]

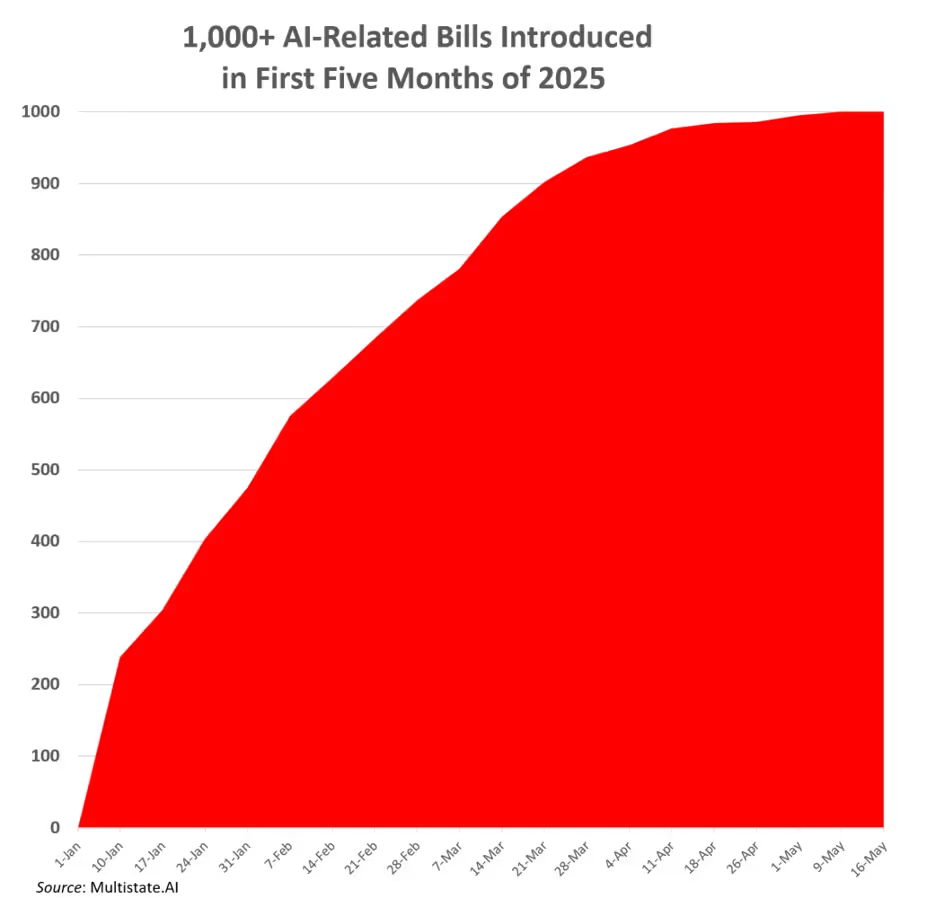

At the same time, however, technological change and the freedom to innovate are coming under attack from more quarters than ever before. This is especially true for the freedom to innovate in the digital sphere, which now includes the potential for comprehensive regulation of advanced computational systems and artificial intelligence (AI) before these technologies have even gained widespread diffusion. In just the first five months of 2025, for example, over 1,000 AI-related bills were introduced across the United States, which is more than eight new AI bills per day.[3] Most of these measures would impose some degree of new government control over algorithmic systems.

This naturally leads to the question: how does America hope to build more and better things as a nation if it is simultaneously going to war against the most important general-purpose technology of modern times? Do the public and our political class want abundance and opportunity, or not?[4]

In this essay, I will discuss why this paradox exists, how it is playing out in the debate over AI policy, and how innovation defenders can rise to this challenge and communicate the importance of technological dynamism and the freedom to use AI and other emerging technologies to improve human welfare.

The essay closes with a variety of solutions to clean up past messes and thoughts on how to avoid getting into new ones to unlock more exciting technology-enabled opportunities for society.

Tool-Making is in Our Nature and the Key to Human Flourishing

Defending the freedom to innovate has been the focus of my life’s work for over three decades, and, with the Digital Revolution, I have been blessed to witness and write about one of the most remarkable technological transformations in human history: the transition from a world of information poverty to one of information abundance. Today, society enjoys an unparalleled degree of ubiquitous, diverse, instantly accessible information and media.[5] Every person is now able to publish and express themselves to the entire planet. “There has never been a better time to be a reader, a watcher, a listener, or a participant in human expression,” observes technology author Kevin Kelly.[6]

Technology made the information revolution possible, and it will also make the computational revolution possible—but only if society is open to it. The key to that will be a strong defense of technological dynamism and a public policy framework rooted in flexibility and forbearance.

Importantly, when I say “technology” made the information revolution possible, I mean to say human action and ingenuity brought about that result. Technology is a widely misunderstood concept. Technology is not some autonomous force the Gods or fate imposes on us. Properly understood, technology simply represents “practical implementations of intelligence” to a task or need.[7]

Benjamin Franklin taught us long ago that we humans are by nature “a tool-making animal” because tool-building is the key to our survival as a species. F.A. Hayek once explained how civilization is “the accumulated hard-earned result of trial and error” and “the sum of experience.”[8] Through incessant experimentation, we discover new and better ways of satisfying human needs and wants to improve our lives and the lives of those around us.[9] Human flourishing depends upon our collective willingness to embrace and defend the creativity and risk-taking that generates the wisdom and growth that propels civilization forward.[10]

Today, however, many critics suggest that modern technological change—and the information revolution in particular—have not really been worth it.[11] They seek to curtail or reverse the policies that have been favorable to producing progress. They call for either a return to a supposed “simpler time,” or at least a slowing the current pace of change to “reclaim our humanity.”[12]

Nowhere is the attitude more evident than in the work of the so-called “degrowth” movement.[13] Degrowth advocates believe that only by forcing humanity into a state of technological stasis can we save civilization. It is not unusual today to hear university professors or other pundits echoing degrowth themes when they suggest “there’s nothing wrong with being a Luddite”[14] because technology is “dehumanizing” us and “will eliminate what it means to be human.”[15] Such critics worry about humanity’s prospects for “surviving progress,”[16] and they argue that instead of being its helpful servant, technology is humanity’s “dangerous master” that we should fear and resist.[17]

The War on Computation Commences

These technology critics have now turned their attention to AI and they are pursuing an all-out war on computation to slow or stop the next major industrial revolution.[18] Employing the same degrowth mentality, some of these critics now call for a strategy of “decomputing,” or embracing radical regulatory steps to curtail advanced algorithmic or computational systems development.[19] In recent years, for example, there have been calls to:

- “pause AI” through some sort of global ban on computational advancement;[20]

- destroy datacenters by airstrike in countries that do not comply with such AI bans;

- develop widespread technological surveillance and censorship systems that could possibly include an Orwellian-named “freedom tag,” which would be a “necklace with multi-dimensional cameras” that allows real-time monitoring of scientists and engineers to ensure they are not engaged in unauthorized AI research.[22]

- have governments nationalize supercomputing facilities, such that government-controlled labs exclusively conduct any “high-risk R&D” on AI;[23] and,

- create an “AI island” where global governments work together “to take control by regulating access to frontier hardware” to limit powerful computational systems.[24]

Beyond these extreme proposals, there have also been many calls for new AI-focused licensing and liability schemes, controls on AI chips and other hardware, and a variety of new international regulatory accords and treaties to control the development and diffusion of AI systems.[25] Finally, a wide variety of new regulatory bureaucracies have been proposed to implement all these new mandates, including a Federal Robotics Commission,[26] an AI Control Council,[27] a National Technology Strategy Agency,[28] and an “F.D.A. for Algorithms.”[29]

The sheer volume of AI regulatory proposals is astonishing.[30] As noted, more than 1,000 AI-related bills were floated in the first five months of 2025.[31] This represents an unprecedented level of political interest in any new emerging technology. Some regulatory measures are already passing at the state and local level, and they are growing increasingly convoluted.[32] These measures often do not even define the term “artificial intelligence” consistently, and they also create differing regulatory requirements for arbitrarily defined business categories such as AI “developers,” “deployers,” and “distributors.”[33] This swelling political activity threatens to create a confusing patchwork of regulatory policies that will entail enormous compliance costs, especially for smaller technology entrepreneurs.[34]

The Opportunity Costs of AI Over-Regulation

It will be hard to achieve a pro-growth “abundance agenda” with so much regulation brewing. The potentially deleterious consequences of these AI regulatory proposals fall into four major categories.

(1) Lost economic growth and opportunity

First, AI is the “most important general-purpose technology of our era” and part of a growing constellation of interrelated and co-dependent technologies and sectors with profound economic and geopolitical significance.[35] AI supercharges what economists call “combinatorial innovation” in which various technological systems “can be combined and recombined by innovators to create new devices and applications.”[36]

This makes AI policy decisions hugely important because a positive, growth-oriented innovation culture will encourage even greater investment and entrepreneurialism across multiple sectors.[37] Heavy-handed AI regulation could undermine this growth potential and the new types of competition and consumer choice it would produce.

(2) Diminished health & well-being

Second, AI and machine learning technologies give humanity the best chance ever to address the most serious ailments and chronic diseases that have proven hard to beat despite decades of effort and considerable public and private spending.[38] Algorithmic systems are likewise helping boost productivity and safety outcomes in other important sectors, especially agriculture and transportation.[39] If policymakers erect regulatory roadblocks to AI-enabled progress in these and other fields, it will limit scientific breakthroughs and undermine human welfare in various ways.[40]

(3) Undermining learning & communication

Third, AI is also the most important information technology of our time. That has profound ramifications for the creation and discovery of knowledge, and for free speech and free inquiry more generally.[41] As Hayek also taught us long ago, “Progress is movement for movement’s sake, for it is in the process of learning, and in the effects of having learned something new, that man enjoys the gift of his intelligence.”[42] He also argued that “the chief aim of freedom is to provide both the opportunity and the inducement to insure the maximum use of knowledge that an individual can accrue.”[43]

AI and advanced computational capabilities offer humanity an unparalleled opportunity to enjoy the gift of our intelligence and go well beyond it to expand our understanding of the world and all that it entails by maximizing the knowledge each of us can accrue and use. Regulatory measures that slow or block the AI revolution represent an attack on humanity’s ability to enjoy the freedom to communicate and learn using cutting-edge knowledge-enhancing technologies.

(4) Undermining geopolitical competitiveness & security

Finally, AI and high-powered computational systems have profound ramifications for global competitiveness and national security. If liberal nations foreclose AI innovation opportunities, autocratic nations—especially China—will quickly fill that gap and convert AI from being a technology of freedom into one of societal repression.[44]

Hudson Institute scholar Arthur Herman speaks of the rising “AI Cold War” with China and argues that “[t]he fate of societies and economies founded on Western liberal principles hangs in the balance—a future that Beijing and the Chinese Communist Party want to replace with their own totalitarian template,” using AI and other advanced technologies.[45] The Soviets aspired to such things during the previous Cold War, but “they never had the scientific, technological, or economic means to carry it out. China does,” Herman argues.

This makes the development of AI strategy, both domestically and internationally, extraordinarily important. China understands that AI is also the most important information technology of modern times and that it has profound potential to influence cultural values and speech policies on a global scale.[46] The Chinese approach of instilling their values of control and surveillance directly into their technological systems, Herman argues, “is a vision that is more frightening, and potentially more catastrophic for human freedom, than anything dreamed up by science fiction.”

Therefore, it is intellectually lazy, and even quite irresponsible, for politicians or pundits to casually suggest American AI advances should be “paused” in the name of limiting AI-related risks when a far greater existential risk exists if China comes to dominate these computational systems first.[47] “Cultures that attempt to block technology for reasons that appear desirable will, all things equal, eventually be dominated by those that embrace it,” notes Braden Allenby of Arizona State University.[48]

The Power of the Status Quo

These are the reasons why AI and the computational revolution are so important, and why it is essential that America be at the forefront of it. Of course, these same factors also make AI—and American leadership in the field—a major regulatory target.

Technological change always disrupts the status quo, which is why innovation has created so many opponents throughout history.[49] In his 1965 book, The Logic of Collective Action, Mancur Olson explained how, when benefits are concentrated and costs are dispersed (across all taxpayers, for example), we can expect special interests to form to take advantage of those benefits—and then protect them.[50] This results in entrenched government programs and policies and chronic rent-seeking by special interests looking to preserve their favored status quo. “The past, in general, is over-represented in Washington,” former Democratic Representative Jim Cooper once noted. “The future has no lobbyists.”[51]

Technology sectors are no exception to these problems. In fact, some of the worst historical examples of cronyism and regulatory capture have occurred in telecommunications and media markets.[52] “Time and again, the losing interest groups created by scientific progress or technological change have been able to convince politicians to block, slow, or alter government support for scientific and technological progress,” says Mark Zachary Taylor, author of The Politics of Innovation. “The losers and their political representatives have interfered with markets, public institutions and policies, and even the scientific debate itself—whatever they can do to protect their interests.”[53] These acts of political favoritism lead to status quo protection and a “captured economy” that undermines dynamism.[54]

Because AI has the potential to become a significant status quo disruptor—culturally, economically, and geopolitically—it will supercharge opposition to change. Many policymakers, pundits, and even industry representatives—both here and abroad—are looking to slow AI innovation and the computational revolution because they want their preferred status quo protected in some fashion.

In her 1998 book, The Future and Its Enemies, Virginia Postrel identified how our modern technological world has united two groups “who would have once been bitter enemies: reactionaries, whose central value is stability, and technocrats, whose central value is control.”[55] Reactionaries “seek to reverse change, restoring the literal or imagined past and holding it in place,” while the technocrats, “promise to manage change, centrally directing ‘progress’ according to a predictable plan,” Postrel argued.[56] Thus, while the reactionaries “celebrate the primitive or traditional,” the technocrats “worry about the government’s inability to control dynamism.”[57]

Permissionless Innovation or the Precautionary Principle?

When it comes to the specific policy instruments used to accomplish those objectives, what often unites reactionaries and technocrats is a desire to impose the precautionary principle on many emerging technologies. In a 2016 book, Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom, I explored how all modern technology policy debates involve a conflict between two different philosophical visions or policy defaults for governing emerging technology: the precautionary principle versus permissionless innovation.[58] Today’s debate over AI’s future will once again come down to which default will govern algorithmic and computational systems.

The precautionary principle embodies a policy preference for stasis over change. Stability and preservation of past policies, professions, or business methods are the priority.[59] As applied through proscriptive rules, the precautionary principle discourages risk-taking and market experimentation in favor of anticipatory regulation of new technologies. Under a strict application of the precautionary principle, innovations are severely curtailed or even forbidden until the creators of those new technologies can prove that their new goods or services will not cause any theoretical harms.

The case against the precautionary principle, I have argued, comes down to the fact that, “living in constant fear of worst-case scenarios—and premising public policy on them—means that best-case scenarios will never come about.”[60] Prior restraints on innovation raise barriers to entry, increase compliance costs, and create uncertainty for entrepreneurs and investors. This undermines societal learning, resilience, and prosperity across society—for governments, organizations, industries, and entire peoples. “Over time, if a society—through its government policies, cultural norms, business practices, and education institutions—makes dynamic activity too hard and too risky, people will become less dynamic themselves,” concludes Civitas Institute executive director Ryan Streeter.[61]

The precise way the precautionary principle leads to this result is by derailing the societal learning curve by limiting opportunities to learn from trial-and-error experimentation with new and better ways of doing things.[62] The societal learning curve refers to the way that individuals, organizations, or industries learn from their mistakes, improve their designs, enhance productivity, lower costs, and then offer superior products based on the resulting knowledge.[63] In his recent book, Where Is My Flying Car?, J. Storrs Hall documents how, over the last half century, “regulation clobbered the learning curve” for many important technologies in the U.S., especially nuclear, nanotech, and advanced aviation.[64] Hall documents how endless foot-dragging or outright opposition from special interests, anti-innovation activists, and over-zealous bureaucrats denied society many important innovations. Without trial-and-error experimentation and risk-taking, social learning and economic growth become more limited, thus undermining the potential for technological improvement and human flourishing.

This is why the precautionary principle is a problematic policy default for AI, and why permissionless innovation represents a better governance principle to help ensure a free, prosperous, and safer society.[65] Permissionless innovation refers to the idea that experimentation with new technologies and business models should generally be permitted by default.[66] Others refer to this idea as the “innovation principle,” or the notion that “the vast majority of new innovations are beneficial and pose little risk, so government should encourage them.”[67] Philosopher Max More goes further and encourages policymakers to embrace a “proactionary principle,” which asserts, “[o]ur freedom to innovate technologically is valuable to humanity. The burden of proof therefore belongs to those who propose restricting new technologies. All proposed measures should be closely scrutinized.” [68]

Elsewhere, I have reformulated More’s proactionary principle as “the innovator’s presumption,” or a policy guideline that holds that entrepreneurs and their innovations should be granted a presumption of liberty and legality when launching new tools. This principle could be written into law by formally stipulating that: “Any person or party (including regulatory bodies) who opposes a new technology or service shall have the burden to demonstrate that such proposal is inconsistent with the public interest.”[69]

Put simply, for dynamism to have real meaning, people should generally be free to innovate. As Eric von Hippel argued in his 2017 book, Free Innovation:

With respect to innovation, the common law principle of bounded liberty informs us that individuals have a right to engage in innovation without needing permission from other people or from governmental entities provided that their actions are not unreasonably dangerous to others and do not violate specific and legitimate legal prohibitions.[70]

Simple Rules for a Complex World

Of course, new technologies sometimes create new dangers. Typically, however, the most important solution to technological risk is still more technological innovation, not widespread repression of innovative processes.

There are also many governance mechanisms to address technological risk that fall short of full-blown precautionary principle regulation. Some of those remedies include consumer protection laws, unfair and deceptive practices regulations, defective product recall authority, and civil rights laws.[71] Many additional common law remedies also exist, such as product liability law, negligence standards, design defects law, breach of warranty policies, property law, contract law, various torts and class actions, and other competition laws.[72] Collectively, legal scholar Richard Epstein refers to all these as “simple rules for a complex world.”[73] They are the time-tested general ground rules for a free society that can evolve to meet new circumstances and technologies.

In fact, most of the potential AI-related harms that concern critics are already illegal under various laws, regulations, and court-based standards.[74] Lina Khan, President Joe Biden’s aggressive chair of the Federal Trade Commission (F.T.C.), admitted that, “The F.T.C. is well equipped with legal jurisdiction to handle the issues brought to the fore by the rapidly developing A.I. sector.”[75] In 2023, Khan and the heads of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, released a joint statement saying that there agencies already possessed the power, “to enforce their respective laws and regulations to promote responsible innovation in automated systems.”[76] Some state attorneys general have issued similar memos which clarify that, as the Massachusetts Office of the Attorney General stated in 2024, “existing state consumer protection, anti-discrimination, and data security laws apply to emerging technology, including AI systems, just as they would in any other context.”[77]

In other words, as Will Rinehart of the American Enterprise Institute correctly concludes, “the best AI law may be the one that already exists.”[78] These existing legal remedies should be fully exhausted before imposing new regulatory schemes. When and where we find policy gaps in existing law, we should only pursue new rules after conducting a rigorous cost-benefit analysis to ensure they are justified.[79] We should narrowly tailor policy remedies so that they do not derail beneficial uses of technology.

Finally, social norms and ongoing marketplace competition also play a role in ensuring a safer technological society. Wisdom and resilience are born of real-world human experiences, constant trial-and-error, and the learning that goes along with “muddling through” adversity.[80] Patience, prudence, and humility are the prime virtues as it pertains to dynamism-friendly public policy.[81]

Application to AI Policy

Permissionless innovation has continuing relevance in AI policy debate and can be applied through some of the same simple principles that spawned the Digital Revolution.[82] Innovation defenders should look to foster a positive policy culture for AI and other related emerging computational technologies by advocating four freedoms:

- Freedom to innovate in AI;

- Freedom to code, compute, and develop applications using AI;

- Freedom to learn using AI; and,

- Freedom to speak and express one’s self using AI.

Innovation defenders should simultaneously work to block precautionary principle-based regulatory controls, including new AI-specific bureaucracies, new AI licensing and liability schemes, algorithmic speech controls, burdensome AI-focused tax schemes, and international AI regulatory control efforts.

Will policymakers rise to this challenge and embrace a pro-freedom AI policy agenda rooted in these principles?

When making the case for a pro-freedom approach to AI, innovation defenders should begin by reminding policymakers that we have been here before. Again, these same permissionless innovation principles guided policymaking for the internet and online activity when the digital marketplace was still nascent. When personal computers (PCs) came on the scenes a generation ago, we did not “pause PCs.” Nor did policymakers require hypothetical State Computer Commissions or a federal Department of Internet Control to perform preemptive “computer impact assessments.” Had the nation adopted that sort of approach, it is unlikely the digital marketplace would have produced the sort of vibrant innovation and investment that we today take for granted. We know this to be true because the European Union (E.U.) essentially did adopt that approach, while America avoided it.

Over the past three decades, a real-world natural experiment in which policy default works best has been playing out on either side of the Atlantic. Europe embraced the precautionary principle while America made permissionless innovation the basis of digital technology policy. At the dawn of the digital age, Europe and America were on relatively even footing in terms of talent and potential investment in the internet and online systems. But the E.U. went on to impose a near endless stream of regulatory mandates on digital markets over the following three decades, including most recently the General Data Protection Regulation, the Digital Markets Act, the Digital Services Act, and now a new AI Act.[83]

America took the opposite path, opting for permissionless innovation with a “light-touch,” market-oriented approach to tech policy.[84] The Clinton administration’s Framework for Global Electronic Commerce was a dynamist policy vision that endorsed a flexible, market-oriented approach for the digital economy.[85]

This trans-Atlantic policy experiment with two very different technology governance defaults yielded starkly different results. By embracing the precautionary principle, the European Union was left devoid of any serious global digital technology leaders as endless layers of regulation decimated their tech ecosystem.[86] This led one journal to label Europe “The Biggest Loser” in the global digital innovation race.[87]

Europe languished due to its repressive policies while America prospered thanks to an embrace of permissionless innovation. Scholars have identified how America’s digital sector became “a growth powerhouse” that drove “remarkable gains, powering real economic growth and employment.”[88] Consider the following statistics:

- America has nineteen of the twenty-five largest digital companies in the world by market cap, but Europe has only two.[89]

- Six of the world’s seven trillion-dollar companies are American, and all of them are major players in AI development.[90] By contrast, Europe has no major AI players in the top twenty-five.

- According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, in 2022 alone, the digital economy contributed over $4 trillion of gross output for the nation, $2.6 trillion of value added (translating to ten percent of U.S. G.DP.), $1.3 trillion of compensation, and 8.9 million jobs.[91] American technology firms have become global leaders in almost every segment of the digital commerce and computing marketplace, and U.S. firms are dominant providers of many of those services in Europe, too.

Meanwhile, AI firms and technologies already benefit, at least so far, from America’s preservation of the permissionless innovation policy model. Stanford University’s 2025 AI Index Report revealed that, in 2024, U.S. private investment in AI stood at $109.1 billion, which was 11.7 times greater than the amount invested by China ($9.3 billion), and 24.1 times the amount invested in the United Kingdom ($4.5 billion).[92] This spread between the U.S. and those nations is higher than at any point over the past decade. Between 2013-2024, U.S. global private AI investment stood at $470.9 billion while China was $119.3 billion and the United Kingdom was $28.2 billion.[93] Finally, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Quarterly Workforce Indicators, U.S. data centers increased more than sixty percent nationally from 2016 to 2023, while to the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the number of people working in data centers grew from 306,000 to 501,000 during that period.[94]

Ideas have consequences, and in this case, the technology policy ideas and policies embraced on one side of the Atlantic clearly drove more growth, development, and opportunity than on the other side.

Freedom Requires Forbearance

This evidence clearly establishes that when the history of the digital revolution is written, it will be American innovators, workers, and policymakers who will be credited with spawning it and benefiting the most from it. Can this success story—and the policy principles that spawned it—prevail in the AI age?

It will all come down to whether the United States is once again willing to embrace freedom. More specifically, from a policy perspective, it will again depend on regulatory forbearance, which was the key to America’s dominance in the digital revolution. As Postrel argued at the dawn of the digital renaissance:

While dynamism requires many private virtues, including the curiosity, risk taking, and playfulness that drive trial-and-error progress, its primary public virtues are those of forbearance: of inaction, of not demanding a public ruling on every new development. These traits include tolerance, toughness, patience, and good humor.[95]

Economic historian Joel Mokyr once observed that, “technological progress requires above all tolerance toward the unfamiliar and the eccentric.”[96] That is just another way of saying progress depends upon policymaker patience and forbearance. There is enormous value in waiting and being humble in the face of uncertainty.[97]

It remains unclear, however, whether most lawmakers today have the same degree of tolerance and patience toward the unfamiliar and the eccentric as they did a generation ago. Then, the internet and personal computers were welcomed, or at least tolerated, as noted, but AI has met with a fair degree of hostility and a flurry of legislative proposals.

There have been some recent signs of hope, however. In January 2020, during the first Trump administration, the Office of Management and Budget sent a memorandum to heads of federal departments and agencies outlining “Guidance for Regulation of Artificial Intelligence Applications.”[98] This memorandum flowed from an E.O. Trump issued in February 2019, “Maintaining American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence.”[99] The guidance document stressed that: “Fostering AI innovation and growth through forbearing from new regulation may be appropriate in some cases.”[100]

More recently, the new Trump administration has shown signs of re-embracing that same forbearance vision. In his first week back in office, President Trump signed a new executive order on “Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence,”[101] and then launched a major “AI Action Plan” proceeding to “define priority policy actions to enhance America’s position as an AI powerhouse and prevent unnecessarily burdensome requirements from hindering private sector innovation.”[102] In February, Vice President JD Vance also delivered a major address about AI policy in Paris in which he noted, “excessive regulation of the AI sector could kill a transformative industry just as it’s taking off, and we’ll make every effort to encourage pro-growth AI policies.”[103] These statements and actions suggest that the Trump administration is serious about addressing policy barriers to AI investment and entrepreneurialism to create “a golden age of innovation.[104]

Many states are looking to preemptively regulate algorithmic systems, but some states are wisely pushing a more balanced approach focused on first evaluating how government bodies are currently using AI, or whether existing governance systems and rules are sufficient for responding to AI developments. Some states have also pursued more experimental “sandbox” or “learning lab” legislative models that would let AI entrepreneurs work with state officials to foster new AI applications through partnerships that mitigate regulatory risks in more flexible ways.[105] Finally, two states have proposed bold “right to compute” bills that would protect the public’s ability to access and use computational resources.[106] Montana’s governor signed their right to compute bill into law on April 21.[107]

Nurturing Innovation Culture vs. Micromanaging the Future

There are other bright spots in the push for renewing societal and economic dynamism. Perhaps the most encouraging development today is the growing interest among scholars and pundits on the political left in advancing a growth and abundance agenda. Yet, the nature of their advocacy and some of the specific steps they recommend make it clear that creating a broad-based, big tent “progress movement” could be challenging.[108] There are important differences between how traditional progress champions have approached these issues versus today’s progressive abundance advocates.

Consider first how some market-oriented proponents of progress speak about dynamism and innovation culture. They commonly analogize to plants and ecologies when suggesting how to think about fostering a nation’s innovation culture. Hayek suggested policymakers should aim to “cultivate a growth by providing the appropriate environment, in the manner in which the gardener does this for his plants.”[109] Similarly, Mokyr teaches us to think of technological innovation and economic growth as “a fragile and vulnerable plant, whose flourishing is not only dependent on the appropriate surroundings and climate, but whose life is almost always short. It is highly sensitive to the social and economic environment and can easily be arrested by relatively small external changes.”[110] More recently, James Pethokoukis speaks of the need for “public policy that helps create a better ecology for scientific and technological progress, business innovation, and high-impact entrepreneurship.”[111]

These progress advocates explain how we must nurture our innovation culture if we want it to grow. We must work to educate each new generation about how innovation works, what it means for every member of society, and why freedom and forbearance are necessary if we hope to constantly replenish the well of creativity and entrepreneurial action.[112] For this to happen, society must be open to risk-taking and dynamic change of all sorts, including the “creative destruction” sometimes needed to grow entirely new ecosystems.[113]

To extend the gardening metaphor, dynamists believe that as the first order of business society needs to clear the weeds out of the way if we desire more growth in the ecosystem. Many parts of America’s innovation governance structure are in desperate need of a good brush clearing.[114] In 2017, Deloitte analysts examined the U.S. Code and found that sixty-eight percent of federal regulations had never been updated and that seventeen percent had only been updated once.[115] Imagine if a private business never updated their plans. How long would they last? Unfortunately, this is the norm for regulatory agencies. Such policy ossification has profound ramifications for a nation’s ability to grow.[116]

It is unsurprising, therefore, that so many modern scholars have explained the tension between stodgy, status quo-protecting policies and the “abundance” agenda they desire. Interestingly, a growing number of these leading abundance scholars identify as being liberal Democrats. A paradox lies at the heart of their work, however. They desire greater growth and progress, but they also seem to want to micromanage it into existence.

In their celebrated new book Abundance, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson call for “a political movement that takes invention more seriously.”[117] They and a new generation of liberal scholars correctly identify the many broken institutions and ossified policies that hold back invention and building. Jonathan Rauch long ago described how “demosclerosis,” or “government’s progressive loss of the ability to adapt,” has become a growing problem.[118] More recently, Steven Teles coined the term “kludgeocracy” to describe how government policies are regularly cobbled together to provide quick-fixes for past problems without ever addressing the underlying causes.[119] Nicholas Bagley has likewise identified how a widespread “procedure fetish” with strict governmental processes and rules all too often derails well-intentioned projects.[120] Finally, legal scholar Philip K. Howard has spent decades warning of these same problems in books like The Death of Common Sense, The Collapse of the Common Good, and The Rule of Nobody.

Two former Biden administration officials have been even blunter in recent appraisals of why some of their best-laid efforts to “build again” failed to deliver on priority agenda items like infrastructure and high-tech services. “It’s the sludge of so many different built-up processes, regulations and ways of doing business,” says Jake Sullivan, President Joe Biden’s national security adviser. “You try to build anything, and you’re stepping into quicksand, and the harder you struggle against it, the more you get sucked into it,” he says.[121] Brian Deese, Former senior advisor to President Biden, says that “progress requires flipping the script and creating a regulatory architecture that encourages building more, not less.”[122] “Creating a government that can build also requires taking on the political processes that uphold the status quo.”[123]

Again, these are all men of the Left who share two interesting traits: a desire to get America building again, but a reluctance to utter the F-word—freedom—when suggesting solutions. More specifically, they are allergic to deregulation as solution to many of these problems. Many left-of-center abundance advocates instead adopt a technocratic approach to micro-managing their preferred type of abundance agenda. They want “a liberalism that builds,” but builds specific things in specific, highly directed ways.[124]

After signing the CHIPS and Science Act in 2022, for example, a massive industrial policy measure meant to revitalize domestic semiconductor and tech capacity, the Biden administration used its new grant-making powers to attach a variety of progressive policy strings to the bill’s grants.[125] These strings included prevailing wage requirements, specified childcare benefits, and limitations on stock buybacks by grant recipients.[126] The temptation to use the power of the purse to pursue social policy objectives proved irresistible, even though it also undercut the CHIPS Act’s primary purpose by slowing grants for new technology initiatives.[127]

Similarly, as part of the massive Bipartisan Infrastructure Act signed into law in 2021, Congress earmarked $42.5 billion for the build out of high-speed internet access in rural areas. Unfortunately, the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program (BEAD) never managed to connect a single home to broadband when Biden was in office. Red tape and unrelated social policy priorities, including labor and environmental mandates, bogged BEAD down.[128] Many other bureaucratic issues and permitting problems, some of which already existed, but many of which were created during the Infrastructure Act’s implementation, also plagued its execution.[129]

In essence, progressives remain torn between a liberalism that builds and a liberalism that embodies business as usual. More generally, these liberal abundance advocates ignore Postrel’s important reminder that a sort of “complex messiness” characterizes markets and dynamism. Alas, the liberal abundance advocates still prefer to have the state steering progress in their preferred directions. They want to replace this messiness and uncertainty “with the reassurance that some authority will make everything turn out right,” as Postel explained.[130]

In fact, in her review of Klein and Thompson’s Abundance, Postrel recalled how, during an earlier debate with Klein, “he made a point of noting how much we disagree, citing my 1998 book The Future and Its Enemies. ‘I am a technocrat,’ he said, a term I use in the book to describe people who promise to manage change, centrally directing ‘progress’ according to a predictable plan.’”[131] Postrel noted that her book argued that true dynamism argues “for a more emergent, bottom-up approach, imagining an open-ended future that relies less on direction by smart guys with political authority and more on grassroots experimentation, competition, and criticism.”[132]

In essence, most of today’s Left-leaning abundance advocates seem to imagine there exists a Goldilocks formula for dialing-in progress just right. It is far more likely, however, that these abundance champions are undermining their own cause by trying to micro-manage the needed regulatory house-cleaning process. They should instead draw their inspiration from past Democratic champions of dynamism and deregulation.

Democrats gave America some of the most successful deregulatory success case studies in recent history. In the late 1970s, President Jimmy Carter appointed economist Alfred Kahn—a self-described “good liberal Democrat”—to serve as chairman of the Civil Aeronautics Board (C.A.B.). With the help of other liberals (including Senator Ted Kennedy, Stephen Breyer, and Ralph Nader), Kahn moved quickly to dismantle the anti-consumer aviation cartels that government licensing, price controls, and entry restrictions had sustained.[133] Aviation markets had long suffered from limited service and higher consumer prices because of these rules. Kahn believed that the cozy relationship between the regulators and regulated companies was such a problem that Congress and the Carter administration should abolish the C.A.B. for good. That is exactly what they did, and today Americans enjoy widespread airline service and competition because Democrats decided dynamism demanded deregulation, not just the tweaking of the old market-rigging regime.[134]

Two decades later, Democrats would take steps to advance technological dynamism again, this time for the internet and digital commerce. Again, it was the Clinton-Gore Framework for Global Electronic Commerce that ensured that the internet and digital commerce and speech would be born free of the sorts of regulations that had encumbered previous information technologies, such as broadcasting and cable. In essence, Democrats helped deregulate the internet preemptively by putting a policy firewall between the old and new information policy regimes. By embracing regulatory forbearance as the prime directive of American internet policy, Democrats ensured that dynamism could take root in digital ecosystems.

If it happened before, it can happen again for AI and other emerging technologies.

Conclusion: The Moral Case for Dynamism

A new age of abundance awaits us, but it will require us to re-embrace freedom and forbearance as the basis of innovation policy. Abundance cannot be micro-managed into existence, but we can absolutely encourage it through smart public policy choices.

Repressing progress has profound consequences for civilization because as Hayek also taught us, “civilization is progress and progress is civilization. The preservation of the kind of civilization that we know depends on the operation of forces which, under favorable conditions, produce progress.”[135]

Building on Hayek’s insight, we can go work harder to ensure those favorable policy conditions by making the moral case for dynamism and the freedom to innovate.[136] Efforts to block innovation and entrepreneurial activities limit our freedom to learn more about the world and improve the human condition, essentially condemning us to the status quo. By challenging our freedom to experiment with new and better ways of doing things, critics would wrongly deny society the opportunities for knowledge and growth creation that serve as the foundations for human flourishing and moral improvement.[137]

Protecting the freedom to innovate also has ramifications for the survival of entire nations and cultures. “A society that neglects the engines of dynamism eventually becomes stagnant,” notes Ryan Streeter.[138] Countries that create a more positive innovation culture enjoy a greater standard of living than those that have not because technological innovation has been a key driver of improvements in human well-being throughout history.[139] As America approaches its 250th birthday, we should re-embrace the entrepreneurial spirit of dynamism that made the United States the most prosperous nation in history.

Adam Thierer is a resident senior fellow with the R Street Institute in Washington, D.C. This essay is based on remarks delivered at the Civitas Institute “Austin Symposium on Economic Dynamism” on April 16, 2025, and an address before the Mont Pelerin Society Regional Meeting in Mexico City on March 18, 2025 for a panel discussion on “AI, Emerging Technologies and Regulation.”

Footnotes

[1] Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, Abundance (Simon & Schuster, 2025). Marc Andreessen, “It’s Time to Build,” Andreesen Horowitz, 2020. https://a16z.com/its-time-to-build. Brian Deese, “Why America Struggles to Build,” Foreign Affairs, March 12, 2025. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/why-america-struggles-build.

[2] Gary Winslett, “Building an Up-Left Politics,” The Rebuild, March 13, 2025. https://www.therebuild.pub/p/building-an-up-left-politics.

[3] “Artificial Intelligence (AI) Legislation,” Multistate.AI, last accessed March 18, 2025. https://www.multistate.ai/artificial-intelligence-ai-legislation.

[4] Thomas Hochman, “Will Anyone Vote for Abundance?” The New Atlantis, No. 78 (Fall 2024): 22–27.

[5] Ryan Murphy, “This is What Peak Culture Looks Like,” Works in Progress, May 20, 2021, https://worksinprogress.co/issue/this-is-what-peak-culture-looks-like.

[6] Kevin Kelly, The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future (Viking, 2016), p. 165.

[7] Frederick Ferré, Philosophy of Technology (University of Georgia Press, 1988, 1995), 26.

[8] F.A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (Routledge: 1960, 1990): 60.

[9] Adam Thierer, “Coping with Technological Change,” in Alice L. Kassens & Joshua C. Hall (eds.), Challenges in Classical Liberalism: Debating the Policies of Today Versus Tomorrow (Palgrave MacMillan, 2023): 229-50.

[10] Adam Thierer, Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom, 2nd ed. (Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2016). https://www.mercatus.org/

publication/permissionless-innovation-continuing-case-comprehensive-technological-freedom.

[11] Brian Merchant, Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech (Little, Brown and Company, 2023).

[12] Shannon Vallor, The AI Mirror: How to Reclaim Our Humanity in an Age of Machine Thinking (Oxford University Press, 2024).

[13] Evgeny Morozov, “Stunt the Growth,” Slate, Jan. 22, 2015, http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2014/01/

degrowth_movement_challenges_more_information_is_always_

better_status_quo.html.

[14] Brett Frischmann, “There's Nothing Wrong with Being a Luddite,” Scientific American, Sept. 20, 2018, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/theres-nothing-wrong-with-being-a-luddite.

[15] David Auerbach, “It’s OK to Be a Luddite,” Slate, Sept. 9, 2015, http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/bitwise/2015/09/

luddism_today_there_s_an_important_place_for_it_really.single.html.

[16] Marc Goodman, Future Crimes (New York: Doubleday, 2015): 392.

[17] Wendell Wallach, A Dangerous Master: How to Keep Technology from Slipping beyond Our Control (New York: Basic Books, 2015). Also see, David Brooks, “Our Machine Masters,” New York Times, Oct. 30, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/31/opinion/david-brooks-our-machine-masters.html.

[18] Nirit Weiss-Blatt, Adam Thierer & Taylor Barkley, “The AI Technopanic and Its Effects,” Abundance Institute, May 2024. https://abundance.institute/articles/the-ai-technopanic-and-its-effects.

[19] Dan McQuillan, “Labour’s AI Action Plan - a gift to the far right,” ComputerWeekly.com, Jan. 14, 2025. https://www.computerweekly.com/opinion/Labours-AI-Action-Plan-a-gift-to-the-far-right.

[20] Future of Life Institute, “Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter,” March 22, 2023, https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments.

[21] Eliezer Yudkowsky, “Pausing AI Developments Isn’t Enough. We Need to Shut It All Down,” Time, March 29, 2023, https://time.com/6266923/ai-eliezer-yudkowsky-open-letter-not-enough/.

[22] Nick Bostrom, “How Civilization Could Destroy Itself—and 4 Ways We Could Prevent It,” TED, April 2019, https://www.ted.com/talks/

nick_bostrom_how_civilization_could_destroy_itself_and

_4_ways_we_could_prevent_it. Nick Bostrom, “The Vulnerable World Hypothesis,” Global Policy 10:4 (Nov. 2019), pp. 455-476. https://nickbostrom.com/papers/vulnerable.pdf.

[23] Samuel Hammond, “A Manhattan Project for AI Safety,” Second Best, May 15, 2023, https://www.secondbest.ca/p/a-manhattan-project-for-ai-safety.

[24] Ian Hogarth, “We Must Slow Down the Race to God-Like AI,” Financial Times, Apr. 13, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/03895dc4-a3b7-481e-95cc-336a524f2ac2.

[25] Keegan McBride and Adam Thierer, “The Trouble With AI Safety Treaties,” Lawfare, Jan. 29, 2025. https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/the-trouble-with-ai-safety-treaties.

[26] Ryan Calo, The Case for a Federal Robotics Commission, Brookings Institution, Sept. 15, 2014, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/RoboticsCommissionR2_Calo.pdf.

[27] Anton Korinek, “Why We Need a New Agency to Regulate Advanced Artificial Intelligence: Lessons on AI Control from the Facebook Files,” Brookings Institution, Dec. 8, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/research/why-we-need-a-new-agency-to-regulate-advanced-artificial-intelligence-lessons-on-ai-control-from-the-facebook-files.

[29] Andrew Tutt, “An FDA for Algorithms,” Administrative Law Review, Vol. 69, No. 1 (2017): 83–123, http://www.administrativelawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/69-1-Andrew-Tutt.pdf.

[30] Adam Thierer, "Don't let the states derail America's AI revolution," The Hill, Mar. 23, 2025. https://thehill.com/opinion/5208637-ai-regulation-china-us.

[31] “Artificial Intelligence (AI) Legislation,” Multistate.AI, last accessed March 18, 2025. https://www.multistate.ai/artificial-intelligence-ai-legislation.

[32] Dean Ball, “The EU AI Act is Coming to America,” Hyperdimensional, Feb. 13, 2025. https://www.hyperdimensional.co/p/the-eu-ai-act-is-coming-to-america.

[33] Madyson Fitzgerald, “As the Trump administration loosens AI rules, states look to regulate the technology,” Stateline, Mar. 21, 2025. https://stateline.org/2025/03/21/as-the-trump-administration-loosens-ai-rules-states-look-to-regulate-the-technology.

[34] Will Rinehart, “How much might AI legislation cost in the U.S.?” Exformation, Mar. 19, 2025. https://exformation.williamrinehart.com/p/how-much-might-ai-legislation-cost.

[35] Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, “The Business of Artificial Intelligence,” Harvard Business Review, July 18, 2017. https://hbr.org/2017/07/the-business-of-artificial-intelligence.

[36] Hal R. Varian, “Computer Mediated Transactions,” American Economic Review, Vol. 100, No. 2. (May 2010), https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.100.2.1.

[37] Tom Davidson, “Could Advanced AI Drive Explosive Economic Growth?” Open Philanthropy, Research Report, June 25, 2021. https://www.openphilanthropy.org/research/could-advanced-ai-drive-explosive-economic-growth; Ege Erdi and Tamay Besiroglu, “Explosive growth from AI automation: A review of the arguments,” Arxiv, Oct. 1, 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.11690.

[38] Adam Thierer, “AI and Public Health Series: Introduction,” R Street Institute Analysis, July 9, 2024. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/ai-and-public-health-series-introduction.

[39] Gale Pooley, “Waymo Drivers Are Way Safer (10x) Than Humans,” Human Progress, Jan. 7, 2025. https://humanprogress.org/waymo-drivers-are-way-safer-10x-than-humans.

[40] Steven Greenhut, “Slow approval of self-driving cars is costing lives,” Orange County Register, Jan. 12, 2025. https://www.ocregister.com/2025/01/12/slow-approval-of-self-driving-cars-is-costing-lives.

[41] Testimony of Greg Lukianoff, Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government, “Hearing on the Weaponization of the Federal Government,” 118th Congress, Feb. 2024. https://judiciary.house.gov/committee-activity/hearings/hearing-weaponization-federal-government-5.

[42] F.A. Hayek, “The Common Sense of Progress,” The Constitution of Liberty (Routledge: 1960, 1990): 41. https://fee.org/articles/the-common-sense-of-progress.

[43] F.A. Hayek, “Responsibility and Freedom,” The Constitution of Liberty (Routledge: 1960, 1990), p. 81.

[44] Adam Thierer, “Ramifications of China’s DeepSeek Moment, Part 1: AI, Technological Supremacy and National Security,” R Street Institute, Feb. 3, 2025. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/ramifications-of-chinas-deepseek-moment-part-1-ai-technological-supremacy-national-security.

[45] Arthur Herman, “China and Artificial Intelligence: The Cold War We’re Not Fighting,” Commentary, July/Aug. 2024. https://www.commentary.org/articles/arthur-herman/china-artificial-intelligence-cold-war.

[46] Adam Thierer, Testimony Before the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology Hearing on “DeepSeek: A Deep Dive,” Apr. 8, 2025. https://www.rstreet.org/outreach/adam-thierer-testimony-hearing-on-deepseek-a-deep-dive.

[47] Scott Alexander, “Why Not Slow AI Progress?” Astral Codex Ten, Aug. 8, 2022. https://astralcodexten.substack.com/p/why-not-slow-ai-progress.

[48] Braden Allenby, “The Dynamics of Emerging Technology Systems,” in Gary E. Marchant, et al, eds., Innovative Governance Models for Emerging Technologies (Edward Elgar, 2013), p. 33.

[49] Calestous Juma, Innovation and Its Enemies: Why People Resist New Technologies (Oxford University Press, 2016).

[50] Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (1965).

[51] Quoted in Mike Masnick, “Hacking Society: It's Time To Measure The Unmeasurable,” TechDirt, Apr. 27, 2012. https://www.techdirt.com/2012/04/27/hacking-society-its-time-to-measure-unmeasurable.

[52] Adam Thierer & Brent Skorup, “A History of Cronyism and Capture in the Information Technology Sector,” Journal of Technology Law & Policy, Vo. 18, No. 2 (2013). https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/jtlp/vol18/iss2/2.

[53] Mark Zachary Taylor, The Politics of Innovation: Why Some Countries are Better Than Others at Science and Technology (Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 213.

[54] Brink Lindsey & Steven Teles, The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality (Oxford University Press, 2018).

[55] Virginia Postrel, The Future and Its Enemies (New York: The Free Press, 1998): 7–8.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Adam Thierer, Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom, 2nd ed. (Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2016).

[59] Norman Lewis, “The Enduring Wisdom of the Crowd,” Spiked, October 24, 2018, https://www.spiked-online.com/2018/10/24/the-enduring-wisdom-of-the-crowd. (Arguing that elites today are, “the most short-term, risk-averse elite in history. What really drives them, above all else, is a desire for stability, predictable outcomes and the maintenance of the status quo.”)

[60] Thierer, Permissionless Innovation, p. 2.

[61] Ryan Streeter (ed.), Dynamism and Its Enemies (The University of Texas at Austin, Civitas Institute, 2025).

[62] Megan McArdle, The Up Side of Down: Why Failing Well is the Key to Success (Viking, 2014). Adam Thierer, “Failing Better: What We Learn by Confronting Risk and Uncertainty,” in Sherzod Abdukadirov (ed.), Nudge Theory in Action: Behavioral Design in Policy and Markets (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016): 65-94.

[63] Adam Thierer, “How to Get the Future We Were Promised,” Discourse, January 18, 2022, https://www.discoursemagazine.com/culture-and-society/2022/01/18/how-to-get-the-future-we-were-promised.

[64] J. Storrs Hall, Where Is My Flying Car? (Stripe Press, 2021).

[65] Adam Thierer, “How Many Lives Are Lost Due to the Precautionary Principle?” Discourse, Oct. 31, https://www.mercatus.org/economic-insights/expert-commentary/how-many-lives-are-lost-due-precautionary-principle.

[66] Thierer, Permissionless Innovation.

[67] Daniel Castro & Michael McLaughlin, “Ten Ways the Precautionary Principle Undermines Progress in Artificial Intelligence,” Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, Feb. 4, 2019, https://itif.org/publications/2019/02/04/ten-ways-precautionary-principle-undermines-progress-artificial-intelligence.

[68] Max More, “The Proactionary Principle (March 2008),” Max More’s Strategic Philosophy, Mar. 28, 2008, http://strategicphilosophy.blogspot.com/2008/03/proactionary-principle-march-2008.html.

[69] Adam Thierer, “Converting Permissionless Innovation into Public Policy: 3 Reforms,” Medium, Nov. 29, 2017. https://readplaintext.com/converting-permissionless-innovation-into-public-policy-3-reforms-8268fd2f3d71.

[70] Eric von Hippel, Free Innovation (The MIT Press, 2017): 128. (“With respect to innovation, the common law principle of bounded liberty informs us that individuals have a right to engage in innovation without needing permission from other people or from governmental entities provided that their actions are not unreasonably dangerous to others and do not violate specific and legitimate legal prohibitions.”)

[71] Adam Thierer, “Flexible, Pro-Innovation Governance Strategies for Artificial Intelligence,” R Street Institute Policy Study No. 283 (April 2023). https://www.rstreet.org/research/flexible-pro-innovation-governance-strategies-for-artificial-intelligence.

[72] Adam Thierer, “The Most Important Principle for AI Regulation,” R Street Institute, Real Solutions, June 21, 2023. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/the-most-important-principle-for-ai-regulation.

[73] Richard Epstein, Simple Rules for a Complex World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995).

[74] Tyler Tone, “AI is new — the laws that govern it don’t have to be,” FIRE Newsdesk, Mar. 28, 2025. https://www.thefire.org/news/ai-new-laws-govern-it-dont-have-be.

[75] Lina Khan, “We Must Regulate A.I. Here’s How,” New York Times, May 3, 2023. “https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/03/opinion/ai-lina-khan-ftc-technology.html.

[76] U.S. Federal Trade Commission, “FTC Chair Khan and Officials from DOJ, CFPB and EEOC Release Joint Statement on AI,” Apr. 25, 2023. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/04/ftc-chair-khan-officials-doj-cfpb-eeoc-release-joint-statement-ai.

[77] Massachusetts Office of the Attorney General, “AG Campbell Issues Advisory Providing Guidance On How State Consumer Protection And Other Laws Apply To Artificial Intelligence,” Apr. 16, 2024. https://www.mass.gov/news/ag-campbell-issues-advisory-providing-guidance-on-how-state-consumer-protection-and-other-laws-apply-to-artificial-intelligence.

[78] Will Rinehart, “The Best AI Law May Be One That Already Exists,” AEIdeas, Feb. 03, 2025. https://www.aei.org/articles/the-best-ai-law-may-be-one-that-already-exists.

[79] Jason Furman, “How to Regulate AI Without Stifling Innovation,” The Wall Street Journal, Nov. 21, 2024. https://www.wsj.com/opinion/how-to-regulate-ai-without-stifling-innovation-regulation-eu-licensing-a2f0d8af.

[80] Adam Thierer, “Muddling Through: How We Learn to Cope with Technological Change,” Medium, June 30, 2014, https://medium.com/tech-liberation/muddling-through-how-we-learn-to-cope-with-technological-change-6282d0d342a6.

[81] Virginia Postrel, The Future and Its Enemies (The Free Press, 1998): 212.

[82] James Pethokoukis, “Permissionless innovation in the Age of AI,” Faster, Please! Apr. 28, 2025. https://fasterplease.substack.com/p/permissionless-innovation-in-the.

[83] Kay Jebelli, “Navigating Europe’s Web of Digital Regulation,” DisCo, Mar. 9. 2022. https://project-disco.org/european-union/030922-navigating-europes-web-of-digital-regulation.

[84] Adam Thierer, “The Policy Origins of the Digital Revolution & the Continuing Case for the Freedom to Innovate,” R Street Institute, Aug. 15, 2024. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/the-policy-origins-of-the-digital-revolution-the-continuing-case-for-the-freedom-to-innovate.

[85] “The Framework for Global Electronic Commerce,” The White House, last accessed March 12, 2025. https://clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov/WH/New/Commerce.

[86] Andrew McAfee, “European Competitiveness, and How Not to Fix It,” The Geek Way, Sept. 23, 2024. https://geekway.substack.com/p/european-competitiveness-and-how.

[87] “The Biggest Loser,” The International Economy (Spring 2022), 44-51.

[88] Makada Henry-Nickie et al., “Trends in the Information Technology sector,” Brookings, Mar. 29, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/research/trends-in-the-information-technology-sector.

[89] “Largest Tech Companies by Market Cap,” last accessed Apr. 25, 2025, https://companiesmarketcap.com/tech/largest-tech-companies-by-market-cap.

[90] Visual Capitalist, “The World’s Top 25 Companies by Market Cap (2024),” Aug. 21, 2024. https://www.voronoiapp.com/markets/The-Worlds-Top-25-Companies-by-Market-Cap-2024-2163

[91] U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “U.S. Digital Economy: New and Revised Estimates, 2017–2022,” Survey of Current Business, Dec. 6, 2023. https://apps.bea.gov/scb/issues/2023/12-december/1223-digital-economy.htm.

[92] Stanford HAI, The 2025 AI Index Report. 2025. https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report P. 251.

[93] Ibid.

[94] Andrew Foote and Caelan Wilkie-Rogers, “Employment in Data Centers Increased by More Than 60% From 2016 to 2023 But Growth Was Uneven Across the United States,” United States Census Bureau, Jan. 6, 2025. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2025/01/data-centers.html.

[95] Postrel, Future and Its Enemies, 212 [emphasis in original].

[96] Joel Mokyr, Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress (Oxford University Press, 1990), 182.

[97] Will Rinehart, “The value of waiting: What finance theory can teach us about the value of not passing AI Bills,” American Enterprise Institute, 2025. https://www.aei.org/technology-and-innovation/the-value-of-waiting-whatfinance-theory-can-teach-us-about-the-value-of-not-passing-ai-bills.

[98] Russell T. Vought, “Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies,” Office of Management and Budget, Nov. 17, 2020. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/M-21-06.pdf.

[99] 84 Fed. Reg. 3967 (Feb. 11, 2019). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/02/14/2019-02544/maintaining-american-leadership-in-artificial-intelligence.

[100] Ibid. At 3.

[101] President Donald J. Trump, “Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence,” Jan. 23, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/removing-barriers-to-american-leadership-in-artificial-intelligence.

[102] The White House, “Public Comment Invited on Artificial Intelligence Action Plan,” Feb. 25, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/02/public-comment-invited-on-artificial-intelligence-action-plan.

[103] JD Vance, “Remarks by the Vice President at the Artificial Intelligence Action Summit in Paris, France,” The American Presidency Project, Feb. 11, 2025. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-the-vice-president-the-artificial-intelligence-action-summit-paris-france.

[104] Michael Kratsios, “A Golden Age of Innovation: Remarks by Director Kratsios at the Endless Frontiers Retreat,” Apr. 14, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/2025/04/8716.

[105] Neil Chilson & Adam Thierer, “A Sensible Approach to State AI Policy,” Federalist Society Regulatory Transparency Project blog, Oct. 9, 2024. https://rtp.fedsoc.org/blog/a-sensible-approach-to-state-ai-policy.

[106] Taylor Barkley, “Protecting our right to compute — A new frontier for freedom,” The Mercury, Mar. 18, 2025. https://themercury.com/commentary-protecting-our-right-to-compute-a-new-frontier-for-freedom/article_caa5093e-040c-11f0-b3d0-63929ef4e745.html

[107] Bill Kramer, “Montana is the First State to Guarantee Computational Freedom,” Multistate.AI, Apr. 25, 2025. https://www.multistate.ai/updates/vol-59.

[108] Adam Thierer, “Where is “Progress Studies” Going?” Progress Forum, Apr. 23, 2022. https://progressforum.org/posts/m2wB8L886v9goeLz9/where-is-progress-studies-going.

[109] F. A. Hayek, “The Pretence of Knowledge,” Nobel Prize lecture, Dec. 11, 1974.

[110] Mokyr, Lever of Riches, 16.

[111] James Pethokoukis, The Conservative Futurist: Hoe to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised (Center Street, 2023), p. 230.

[112] Matt Ridley, How Innovation Works: And Why Flourishes in Freedom (Harper Collins, 2020).

[113] Arthur Diamond, Openness to Creative Destruction: Sustaining Innovative Dynamism (Oxford University Press, 2019).

[114] Adam Thierer, “Spring Cleaning for the Regulatory State,” The Daily Economy, May 23, 2019. https://thedailyeconomy.org/article/spring-cleaning-for-the-regulatory-state.

[115] Daniel Byler, Beth Flores & Jason Lewris, “Using Advanced Analytics to Drive Regulatory Reform: Understanding Presidential Orders on Regulation Reform,” Deloitte, 2017, https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/public-sector/articles/advanced-analytics-federal-regulatory-reform.html.

[116] Bentley Coffey et al., “The Cumulative Cost of Regulations,” Mercatus Center Working Paper, April 2016, https://www.mercatus.org/publication/cumulative-cost-regulations.

[117] Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, Abundance (Simon & Schuster, 2025), p. 135.

[118] Jonathan Rauch, Government's End: Why Washington Stopped Working (1999), p. 125.

[119] Steven Teles, “Kludgeocracy in America,” National Affairs, Fall 2013, https://www.nationalaffairs.com/publications/detail/kludgeocracy-in-america.

[120] Nicholas Bagley, “The Procedure Fetish,” Michigan Law Review, Vol. 118, No. 3, 2019. https://michiganlawreview.org/journal/the-procedure-fetish.

[121] Ezra Klein, “Biden’s Team Wishes They’d Moved So Much Faster,” The New York Times, Apr. 13, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/13/opinion/doge-abundance-government-bulding.html.

[122] Brian Deese, “Why America Struggles to Build,” Foreign Affairs, March 12, 2025. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/why-america-struggles-build.

[123] Ibid.

[124] Ezra Klein, “What America Needs Is a Liberalism That Builds,” The New York Times, May 29, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/29/opinion/biden-liberalism-infrastructure-building.html.

[125] Scott Lincicome, “Social Policy with a Side of Chips,” Cato Institute Commentary, Mar. 8 2023. https://www.cato.org/commentary/social-policy-side-chips.

[126] Bryan Riley, “Biden Administration: Have Some Strings With Your CHIPS,” NTU Blog, Feb. 28, 2023. https://www.ntu.org/publications/detail/biden-administration-have-some-strings-with-your-chips.

[127] Adam Thierer, “This Is What Happens With Industrial Policy,” Wall Street Journal, Mar. 5, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/industrial-policy-chips-act-semiconductors-biden-special-interest-fa2e21e6.

[128] Susan Ferrechio, “Americans still waiting on Biden broadband plan; rural high-speed internet stuck in Dems’ red tape,” The Washington Times, June 18, 2024. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2024/jun/18/bidens-425-billion-rural-high-speed-internet-plan-.

[129] Gabe Horwitz & Alexander Laska, “Barriers to Building,” Third Way Report, Feb. 27, 2025. https://www.thirdway.org/report/barriers-to-building.

[130] Ibid., 19.

[131] Virginia Postrel, “Lawn-Sign Liberalism vs. Supply-Side Progressivism,” Reason, March 18, 2025. https://reason.com/2025/03/18/lawn-sign-liberalism-vs-supply-side-progressivism.

[132] Ibid.

[133] Adam Thierer, “20th Anniversary of Airline Deregulation: Cause For Celebration, Not Re-regulation,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder, Apr. 22, 1998. https://www.heritage.org/government-regulation/report/20th-anniversary-airline-deregulationcause-celebration-notre.

[134] Alfred E. Kahn, "Surprises of Airline Deregulation," American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 78, no. 2 (May 1988), p. 316-22.

[135] Hayek, Constitution of Liberty, 40.

[136] Adam Thierer, “Humanism, Ethics, and Responsible Innovation,” in Evasive Entrepreneurs & the Future of Governance (Cato Institute, 2020), p. 183-204.

[137] Ryan Streeter, “Dynamism as a Public Philosophy,” National Affairs, No. 63 (Spring 2025). https://www.nationalaffairs.com/publications/detail/dynamism-as-a-public-philosophy.

[138] Ryan Streeter, “American Aspiration: Our Anti-Dynamism Problem,” Civitas Institute, Apr. 9, 2025. https://www.civitasinstitute.org/research/american-aspiration-our-anti-dynamism-problem.

[139] James Broughel and Adam Thierer, “Technological Innovation and Economic Growth: A Brief Report on the Evidence,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Mar. 4, 2019. https://www.mercatus.org/publications/entrepreneurship/technological-innovation-and-economic-growth.

Download as PDF

This white paper was published as part of the Civitas Institute's Dynamism Outlook series.

Economic Dynamism

The Causal Effect of News on Inflation Expectations

This paper studies the response of household inflation expectations to television news coverage of inflation.

.avif)

The Rise of Inflation Targeting

This paper discusses the interactions between politics and economic ideas leading to the adoption of inflation targeting in the United States.

The Housing Crisis

Soaring housing costs are driving young people towards socialism—only dispersed development and expanded property ownership can preserve liberal democracy.

.jpeg)

America Needs a Transcontinental Railroad

A proposed merger of Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern would foster efficiencies, but opponents say the deal would kill competition.

Trump's Troubling Economic Turn

How far will current economic regulations go in the Trump White House?

The Poverty of Vanceonomics

At the core of Vanceonomics is a preferential option for government intervention.

.jpg)

.jpg)