The Hidden Costs of Expanding Deposit Insurance

Legislators should remove regulatory barriers to market-driven alternatives that foster genuine discipline and stability.

In the wake of the failure of Silicon Valley Bank in 2023, there is bipartisan support, in the form of the Main Street Depositor Protection Act, for legislation to drastically increase deposit insurance limits. Deposit insurance, intended to protect consumers in the event of bank run, may seem like a good idea, but it comes with hidden distortions and costs that outweigh any perceived benefit. Expanding deposit insurance will only exacerbate financial risk and regulatory dependence, imposing costs on banks, their customers, and taxpayers.

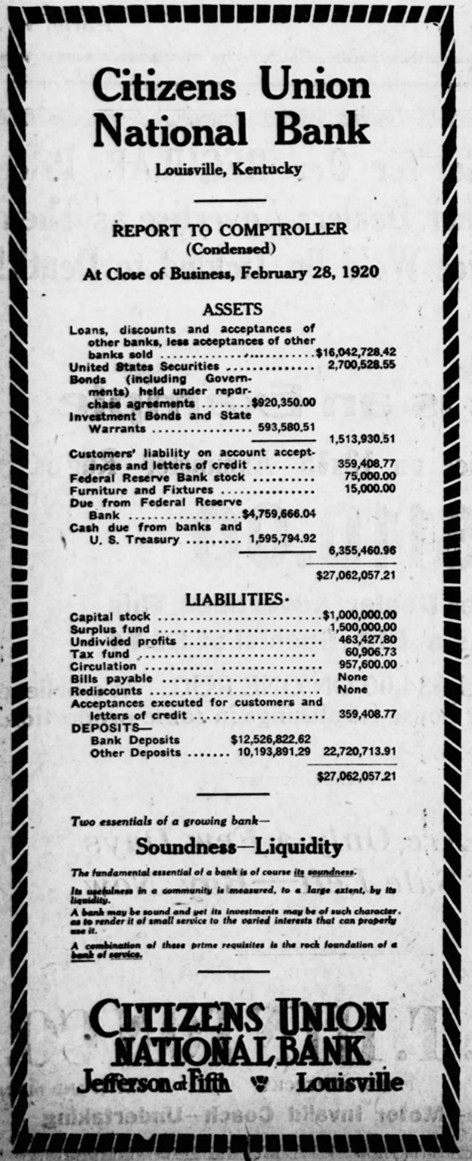

What is the harm in protecting depositors? Let’s focus on the distortion of incentives. Before the advent of deposit insurance, at the state or federal level, banks commonly advertised their balance sheets. For instance, this clipping from The Bourbon News (Paris, Kentucky) on March 12th, 1920 is a common example:

Banks submitted these statements to regulatory authorities and could be held liable for misstatements. This provided bank customers with an indication of the financial soundness of the institution and its cash reserves.

Consumers, who could lose their deposits, would undertake due diligence prior to entrusting their savings to a financial institution. They had the incentive to ask questions and monitor their bank. Large depositors would spread their savings across multiple unconnected banks. Financial institutions, engaging in clearing transactions with each other, would also financially monitor their peer institutions. If a bank started to acquire too much risk or the value of its assets threatened to dip substantially, they would exert pressure for correction, provide resources, or, if they failed to correct course, refuse to deal with them.

Bank runs, similar to a corrupt politician being voted out of office or a mismanaged company falling into bankruptcy, tended to be provide corrective discipline on banks. Banks thus had the incentive to adopt the discipline required to earn a reputation for financial security.

There was the possibility for rumor-based runs, of course, but financially sound banks could successfully resort to private mechanisms, ranging from loans from peer institutions and changes in management, to temporary suspension of redemption, to quickly stop unfounded panics. Comparing states with state-level deposit insurance to those without it, Charles Calomiris in The Journal of Economic History, finds that “insurance systems that relied on self-regulation…were successful while compulsory state systems were not.”

With the advent of first state, and then federal, deposit insurance (the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was started in 1933), it undermined the incentives for consumer and peer-financial institutions to monitor banks. In fact, the incentives encouraged excessive risk-taking. How so? Customers, knowing that they were protected by the deposit limits would forgo what previously would have been a prudent and common-sense review–and ongoing monitoring–of their bank’s financial soundness. Rather, depositors would simply deposit their funds haphazardly in the bank offering the highest return. This encouraged banks to increase the risks of their portfolios. The incentives for interbank monitoring, similarly, were drastically undermined. This may sound far-fetched, but the data confirms it. Deposit insurance is associated with the increased probability of both bank failures and financial crises.

The predictable governmental response to the increased risk created by deposit insurance is more financial regulation, which often comes with additional burdensome and oftentimes unnecessary compliance costs and distortions of incentives. As we know from decades of financial regulation experience, top-down regulation has severe blind spots. It tends to generate systematic risks by encouraging all banks to undertake similar, rather than diversified, risks. It reduces the incentives for innovative or tailored approaches to risk mitigation by reducing the need for institutions to compete on safety. Like deposit insurance, excessive regulation on regulators, who suffer from knowledge and incentive problems in determining and enforcing regulation, reduces the incentives for bank customers to undertake due diligence. For instance, while regulators properly identified the excessive interest rate risk that Silicon Valley Bank faced, they failed to correct the problems due to accounting regulations that prevented them from hedging their risk appropriately. Reliance on regulators was misplaced.

Increased compliance costs associated with increased regulation often create incentives to merge with larger banks, which, in turn, strengthen the argument for “too big to fail” bailouts when things inevitably go wrong. As we learned with the Financial Crisis of 2007, despite warnings from economists, increasing the percentage of the financial sector covered by implicit guarantees encouraged excessive risk-taking, often leading to costly bailouts.

In addition to the costs of all these distortions and the ensuing regulatory patches, federal deposit insurance is also underpriced, further increasing the program's costs. Who bears these costs? Directly, it is banks and their customers, but ultimately, it is taxpayers who are on the hook for bailing out the system. Thomas Hogan and William Luther, in comparing the costs and benefits of the federal deposit insurance, find that they “clearly exceed the costs” and that “the implicit costs of government-provided deposit insurance are real economic costs borne by taxpayers.”

The proposed Main Street Depositor Protection Act would increase deposit insurance from its current limit (set in 2010) of $250,000 to an astounding $10 million. The figure below shows these limits in inflation-adjusted terms (CPI-U) since implementation in 1933:

The documented costs of deposit insurance described above were observed when deposit insurance was set at a much lower level. Raising the limit can be expected to drastically amplify these costs and the distortion of incentives by eliminating the incentive for much larger banking clients to monitor the soundness of the banks in which they deposit funds. It will also, necessarily, increase the costs of rescuing banks, putting taxpayers at substantially more risk.

Legislators should strive to enhance the financial stability of our banking system. More government regulation, especially deposit insurance with its well-studied adverse incentives and implicit costs, however, will only amplify risks and costs. Rather than expand misguided top-down solutions, legislators should remove regulatory barriers to market-driven alternatives that foster genuine discipline and stability.

Daniel J. Smith is a Professor of Economics in the Jones College of Business and Director of the Political Economy Research Institute at Middle Tennessee State University.

Economic Dynamism

Unlocking Public Value: A Proposal for AI Opportunity Zones

Governments often regulate AI’s risks without measuring its rewards—AI Opportunity Zones would flip the script by granting public institutions open access to advanced systems in exchange for transparent, real-world testing that proves their value on society’s toughest challenges.

The Causal Effect of News on Inflation Expectations

This paper studies the response of household inflation expectations to television news coverage of inflation.

Downtowns are dying, but we know how to save them

Even those who yearn to visit or live in a walkable, dense neighborhood are not going to flock to a place surrounded by a grim urban dystopia.

The Housing Crisis

Soaring housing costs are driving young people towards socialism—only dispersed development and expanded property ownership can preserve liberal democracy.

The Economic and Constitutional Vices of California’s “Once-only” Wealth Tax

California's proposal to tax billionaires seems at first menacing, but could have drastic negative consequences for the future of the state.

.webp)

California’s Proposed Billionaire Tax and Its Portents for Normal People

The deeper significance of California's billionaire tax is in how it redefines what it means to own property in the United States.

.avif)

.jpeg)

.jpg)