Ulysses Revisited

Presidential overreach threatens Latin American democracies and the U.S., with growing discretion, weakened checks, and populist abuse.

The region must find ways to limit presidential Powers.

The current Colombian president, Gustavo Petro, has not complied with at least four different decisions issued by high courts that demanded he retract insults and calumnies he has expressed against common citizens. Nothing has happened. Paraphrasing George Orwell's 1984, it seems that we are all equal under the law, but some are more equal than others.

And this is not a problem exclusive to Colombia. In recent years, we have gathered increasing evidence of a problem that was previously unnoticed in the presidential systems prevalent in the region: they grant excessive discretion to presidents and their governments. This discretion is increasingly becoming a threat to our democracies and liberties.

We are witnessing the abuse of presidential powers. In Mexico, the executive is becoming all-powerful. In the United States, according to data of The American Presidency Project of UC Santa Barbara, the president has issued 161 executive orders during his first months in office. In El Salvador, the leader boasts of being a dictator. In Colombia, the president harasses and insults his opponents day after day and, as stated before, he and some of his ministers do not even comply with judicial mandates. In Argentina, the president has been granted almost unlimited powers. In Brazil, government fiscal decisions have led to a devaluation crisis that remains unresolved.

To date, the only countries that have not exhibited this issue are Costa Rica, Panama, and Uruguay. But it does not mean their institutional structures are immune to it. As in the rest of the region, it seems that limits to the exercise of power depend more on personalities, ethical restrictions, and, as Levitsky and Ziblatt called them in their How Democracies Die, hitherto consensual unwritten rules.

It could be countered that presidentialism has always functioned in this manner, and that presidents require leeway and discretionary powers. However, the task of institutions is to minimize the probability of abuse and excesses, no matter who is in power. This becomes paramount in a context in which the type of leaders as well as the conception of government is transforming. Populist leaders, who despise limits, democracy, and accountability, are being elected. Societies are conceding more tasks to their governments. In this sense, facts compel us to reconsider our understanding of power and discretion.

The latter cannot be a superior end when it affects democracy and freedom. However, this appears to be the case: in Colombia, for example, the president has threatened Congresspeople with unconstitutional dismissal if they do not approve his proposals. Before, his followers pressed the Constitutional Court in a decision, not just by protesting outside the Court´s building, but also by causing the justices to leave the building because the decision was contrary to the president´s interests.

Another counterargument could be that it is better to have presidents who have the power and decision-making authority to advance their agendas and solve social problems. The real dilemma is how to do that, without threatening institutional limits and the rule of law.

Leaders have realized that they can govern by decree and use these instruments to avoid the principle of checks and balances. It may come to mind the cases of Mr. Trump in the US or that of Mr. Milei in Argentina. Although they have governed through decrees, the principle of checks and balances remains in place in these countries. In the US, Trump´s decisions have been challenged in the Courts, and other decisions have been supported by Congress.

Besides, recent and current leaders have preferred conflictual relationships with the other branches of power. We have the case of Castillo in Peru, which led to his dismissal, as well as the tensions with the judiciary in Bolivia and Colombia.

To exacerbate the situation, leaders such as those in Mexico, El Salvador, Colombia, and even Chile and the US, have come to assume their political platforms and promises as unquestionable due to an alleged popular mandate. It is essential to acknowledge the problem before all countries in the region follow a direction that Nicaragua or Venezuela has already taken, and which appears to be the path being followed by El Salvador.

Why is it important to address this problem in the region? The extension of political power in one or very few people can be self-fulfilling. Once a door is opened, it is difficult to close it back. This could lead to unlimited powers. Second, since political powers are exercised in and for economic purposes, such intervention negatively affects efficiency, perspectives on wealth creation, and prosperity. It is not only cronyism, rent-seeking, and corruption, but discretionary decisions in economic activities are hindered by the lack of specific and contextual information that only economic agents have when participating in their transactions. Third, unlimited powers, paired with populist leadership, affect harmony and pacific relationships among countries in the region.

We may be facing a turning point in the region, towards presidential regimes that lean towards authoritarianism, economic nationalism, and personalization. This could be a return to the dynamics of power during the dictatorships of the second half of the twentieth century. For this reason, the extent of presidential powers, the discretion they provide, and the loopholes we have witnessed in the region during recent years have become a conspicuous feature of our political systems that concern us all.

The United States has a significant role to play in addressing this problem. First, it must again lead by example by solving and addressing its own problems of loopholes and abuses in the exercise of presidential powers. This country has been the beacon of limited power, and it must be so again. Second, this can be a political focus of the relations in a period in which protectionism and the reduction of international aid appear to be enduring tendencies in American foreign policy. A bet in this sense would be a winning strategy for the US, its security, its prosperity, as well as a much-needed legacy for Latin-American countries.

Javier Garay is a Professor and researcher of international political economy, Faculty of Finance, Government and International Relations, University Externado of Colombia. His most recent book is Ideas erradas, acciones equivocadas: Cómo el contexto internacional impide la generación de desarrollo.

Economic Dynamism

The Causal Effect of News on Inflation Expectations

This paper studies the response of household inflation expectations to television news coverage of inflation.

.avif)

The Rise of Inflation Targeting

This paper discusses the interactions between politics and economic ideas leading to the adoption of inflation targeting in the United States.

Why Can't the Middle Class Invest Like Mitt Romney?

Why can’t middle-income Americans pay effectively no taxes on investments like the wealthy do?

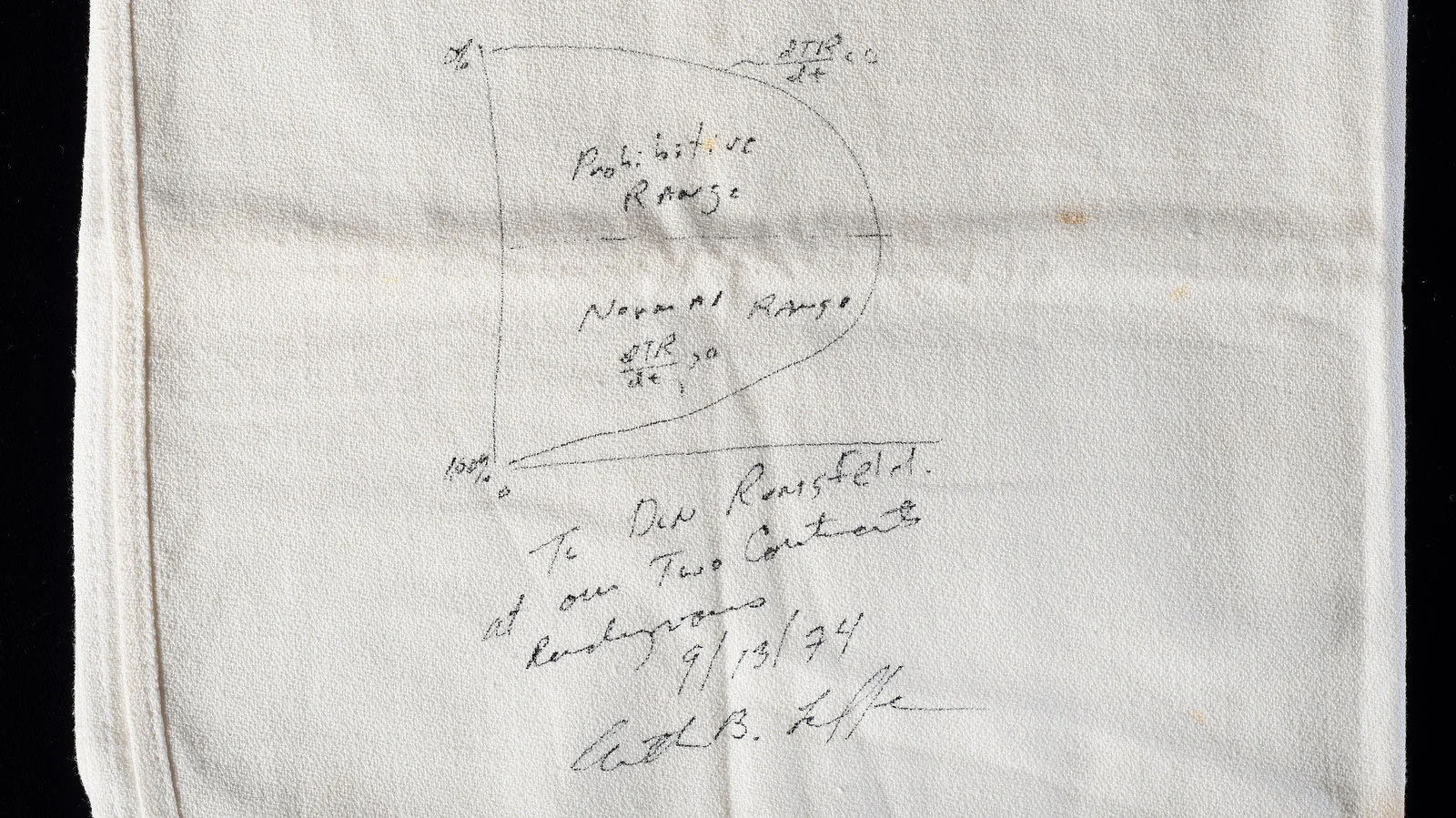

The Revenge of the Supply-Siders

Trump would do well to heed his supply-side advisers again and avoid the populist Keynesian shortcuts of stimulus checks or easy money.

.jpg)

.jpg)