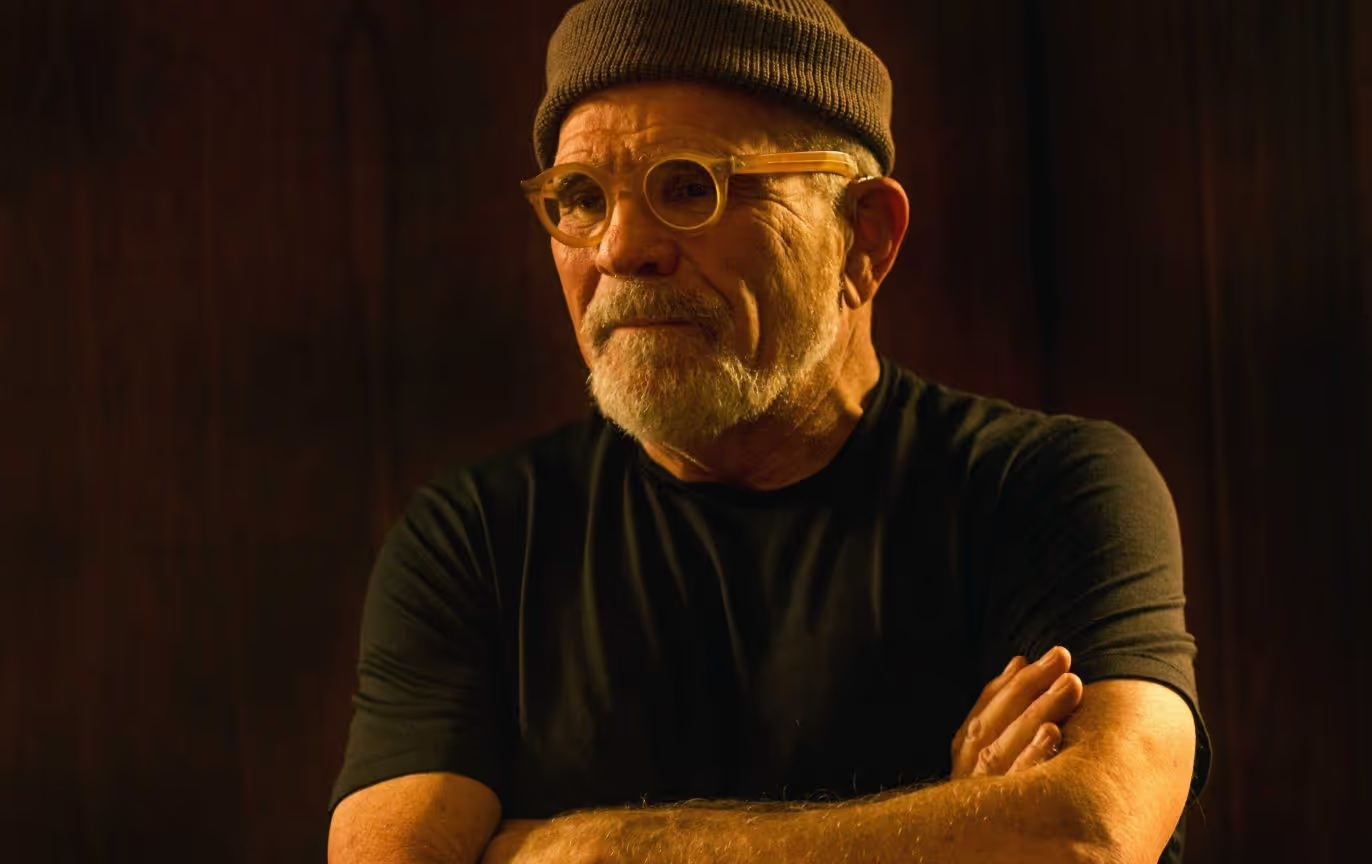

The Education of David Mamet

What kind of artist can David Mamet be in 2025?

If there ever is a playwright who abhorred and explicitly rejected the culture of political correctness, it’s David Mamet. Many of his plays, like House of Games and Glengarry Glen Ross, were made into films (House of Games was directed by Mamet himself), and he also wrote a screenplay for Wag the Dog (1997), Hoffa (1992), and The Untouchables (1987), to name just a few films. His works are imbued with that singular American, Chicago-tough manliness, that comes through even in his female characters.

He has plenty to say about our culture and what it means to be human in today’s bizarre, inhuman world. His new book, The Disenlightenment: Politics, Horror, and Entertainment, touches upon many different aspects of America in an upheaval. Composed as a series of essays, The Disenlightenment has Mamet’s signature writing style. He takes many different paths, meandering through the cultural artifacts of America, but always comes back to the central idea and origin of his thought. “This book,” writes Mamet, “is an attempt to identify a seemingly unconnected set of symptoms as a single disease.”

One of the questions that plagues any normal person (and certainly any normal American) is what has happened to my (our) world? Although Mamet draws clear divisions between conservatives and leftists, he perhaps misses that such divisions are becoming increasingly meaningless. At this point (especially with the start of Covid), the cultural fight isn’t between our usual understanding of cultural lines–conservative or liberal–but between sanity and insanity. Although Mamet’s explorations make it quite clear who is sane and who is insane, he still maintains the usual ideological divides. What seems to connect much of conservative thought to the sanity/insanity divide is that those who reject the surreality of woke ideology or public health tyranny are slowly discovering that many of the reasons why they do so track closely with traditional conservative approaches.

This is not necessarily wrong for Mamet to do. At the core of the cultural and political problems is the difference between the Weltanschauung–a particular metaphysical disposition that is found in both conservatives and liberals. The Left generally relies on the Marxist ideology, and the Right is striving to escape the ideology and institute a free market, be it economic or cultural. The conservative is confident in both reason and faith that there is a reality we can know and draw from in understanding the profitable use of our freedom.

Of course, since so many things have shifted (for better or worse), those old intellectual divisions are increasingly more difficult to accept. Today’s Marxism is strangely intertwined with extreme oligarchical capitalism, with a good dose of surveillance. It is a new breed of problems. Conservatives now realize that many corporations formed too close a nexus with the previous progressive government.

Mamet sees that we are facing something different. Yet, he continuously points out that we are still experiencing the human condition, even though technology has been moving swiftly, making us think that the life we’re living is out of reach, out of control, and most importantly, out of time. In other words, we are facing the reality of mortality and struggle to accept it.

For all the progress we have made, we have been intellectually devolving. What does this mean in the American context? Mamet is mostly concerned with the inner workings of America, and like many of us in our own lives, is wondering where someone like him fits in. The institutions that are firmly rooted in religion appear to be disappearing but only to be replaced by something quite similar. Family is one of the cornerstones of a civilized society, and Mamet rightfully observes the attempts at its destruction. “The modern left works,” writes Mamet, “consciously or not, to destroy the family as the basic unit of loyalty and replace it with allegiance to the state…” As Camille Paglia argued in Sexual Personae, the Left sees the government as a “tyrant father,” but at the same time demands that the same state “behave as a nurturant mother.”

There is an inherent contradiction in such a worldview. It doesn’t help that the mainstream, popular culture has presented family in a negative light. As Mamet writes,

The nuclear family has been eviscerated–by technology, contraception, penicillin, travel, and so on. Its decay has been ascribed to the champions of its demise: humanism, globalism, and atheism-as-reason. But these are only the beneficiaries of its decay. Membership in our various correct-thinking groups is actually an unconscious attempt to reconstitute the family–that group which might offer protection. Just like life in the urban gangs.

What Mamet is essentially pointing to is that there is something inherent, if not biological, in us that gravitates toward being part of a family and community. The problem with the Left is that its idea of the family is based purely on ideology that shapeshifts according to the latest harmful fad. Family can demand nothing of persons; instead, their autonomy redefines family. Much like technology, the ideology itself is “evolving” into an even greater abyss of destruction. But it may start to destroy itself, as any ideology inevitably does.

Being a playwright, film director, and screenwriter, Mamet is concerned with art. Movies are his business, in every sense of the word. Any good filmmaker is fascinated by the human condition and tries to find out what makes us tick. Mamet, too, has established his talent time and time again, and his observations, particularly in the film industry, are extremely valuable.

We hear a lot about A.I. (artificial intelligence, although more like artificial inanity and nuisance) replacing the real artist, and creating “content.” Apart from political correctness, “content” is another anathema to art and creativity. But it began even before silly internet creations and democratizing videos. Streaming services, such as Netflix, ushered in a time of uncreativity. The streaming service, or the corporation,

buys [the product] in bulk, with neither time nor interest in that which one might call artistic integrity, which a comptroller, looking at numbers alone, could only understand as insubordination. The talented–those disposed and able to bring their idiosyncratic vision (art) to manufacturing–are as much of an obstruction as Chinese devotees of feng shui would be to the Hyundai production line.

Mamet is rightly using the economic framework to explain this phenomenon. We only need to take a closer look at Netflix, for example, and notice the cookie-cutter nature of the films and shows. Whether the films and shows are American, Polish, German, or Spanish, they all have common topics and threads: infidelity, gruesome murders, dystopian futures. Everyone looks the same and acts the same. There are no cultural, ethnic, or national differences, but a certain attitude toward life is set up that combines globalist ideology with extreme consumerism and acquisitiveness. Globalist ideology is just another variation of communism, which was never really fully eradicated. It seeks destruction of human individuality and singularity, as well as a new class of marginalized people. This is where Marxism and capitalism join together to create not just a monster, but a mutant that has imposed itself onto everyone via technology.

The state of the film and the threat that artists are under because of A.I. is an indication of a different kind of totalitarianism than we associate with Communism or National Socialism. It builds on itself, and then, like rhizomes or weeds, it grows uncontrollably. We cannot “contain” the Internet anymore (perhaps the sad part of this is the thought that we could), and this explosion of chaos, which Mamet is trying to make sense of, is affecting everything authentic. Of course, art is one of those authentic things.

Mamet is not a philosopher and does not concern himself much with aesthetics as a philosophical category, nor does he focus on the authenticity of art. Yet that is at the heart of the cultural issues he brings up. Both the creation and experience of art rely on an idea of encounter and a firm rejection of ideology. This is why there is no such thing as “conservative” or “leftist” art. It either is or isn’t. The voice of an artist should not be silenced. Mamet is clear on that throughout his book.

Where does Mamet himself fit into this cultural setup that we are currently experiencing? Will those who consider themselves on the left stop appreciating Mamet’s incredible creative output? Is he supposed to be thrown into the dustbin of history because he’s just a manly, macho misogynist? Of course, I am playing devil’s advocate here: Mamet is anything but that; he is a man who has, in his work, brilliantly expressed masculine thrusts and feminine desires. This is what makes him compelling.

Still, one wonders where our culture is heading. Who will read Mamet now that he has, in the last few years, voiced his conservatism? The answer that seeks more questions is perhaps found on the book jacket itself with blurbs and generic endorsements from Mark Levin, Megyn Kelly, and Ben Shapiro. I have no judgment for each of these individuals in the sphere in which they work. However, I cannot help but feel a sense of sadness for our culture. Surely, David Mamet deserves better, or more precisely, other. The question then becomes: what kind of artist can David Mamet be in 2025?

Nevertheless, Mamet’s explorations remain authentic and singular. Regarding the proliferation of content as art, Mamet asks, “How will it all end?” He doesn’t think it will but that it

will continue, willy-nilly: the unfolding Grand-Guignol of human nature, rushing like the wild river in flood, unchecked and so on…while some in the Lowlands flee or pray, and some, thinking themselves immune, picnic on the high ground, clucking at the spectacle and suggesting to each other that Something Must Be Done.

It would appear that we are stuck, or at least that is what Mamet is implying. He doesn’t really give us the solution in this case, but then again, he doesn’t claim to be a doctor, only a diagnostician. In fact, one of the big signs of this disease he’s trying to diagnose is repression. This repression is not necessarily sexual, although we are indeed living in a sterilized, erosless environment. Rather, it is a repression of being itself. A leftist is all too happy to give up on ontological sovereignty.

It’s not the democracy that dies in darkness, as we are constantly berated and reminded about, but the liberal. He or she (or whichever pronoun they/them prefer) will remain in darkness, and thus not enlightened, while perversely pretending that they have enlightenment, and the traditional person, does not. This is the crucial, if not fundamental, element in understanding the leftist mind, and much of it comes down to self-loathing.

Although Mamet does not mention it here, another contradiction emerges–self-loathing is coupled with an extreme form of narcissism. Speaking of change, Barack Obama famously said, “We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.” Spiritually, there is a gnostic, Manichean quality about the proponents of globalist ideology. They reject God, yet they must find a way to replace that reality. They elect themselves as the arbiters of right and wrong. We see these in globalist organizations such as the World Economic Forum or the European Union itself. The key is always agitation and disruption (in the United States, Obama ushered in the style of Saul Alinsky), and without being able to let go of repression, self-loathing, and ultimately, compliance. As Mamet writes, “The Left’s control of its co-opted mass is Pavlovian.”

Are we running out of time? First, we have to define time since we have been forced to live in a vat, a place where past and future do not exist, and the present feels like cryogenic preservation. Mamet is neither pessimistic nor optimistic in his conclusions, if there are any. He expresses his love for America and acknowledges that he has “prospered under the American right to freedom of expression.” But the Chicago Jewish cynic emerges here too: “Throughout my life I’ve been writing my obituary. Or perhaps my autobiography.” It is a beautiful juxtaposition of an American artist, who is of the place, namely Chicago, and yet who transcends it as well. This is the inherent complexity of an artist: he ought to be nationless, placeless, even languageless. But Mamet proves that such a thing is impossible. And thank God for that.

Emina Melonic’s work has been published in The New Criterion, National Review, The Imaginative Conservative, New English Review, Law & Liberty, American Greatness, and Splice Today, among others.

Pursuit of Happiness

The Rise of Latino America

In The Rise of Latino America, Hernandez & Kotkin argue that Latinos, who are projected to become America’s largest ethnic group, are a dynamic force shaping the nation’s demographic, economic, and cultural future. Far from being a marginalized group defined by oppression, Latinos are integral to America’s story. They drive economic growth, cultural evolution, and workforce vitality. Challenges, however, including poverty, educational disparities, and restrictive policies, threaten their upward mobility. Policymakers who wish to harness Latino potential to ensure national prosperity and resilience should adopt policies that prioritize affordability, safety, and economic opportunity over ideological constraints.

Exodus: Affordability Crisis Sends Americans Packing From Big Cities

The first in a two-part series about the Great Dispersion of Americans across the country.

The AI Future: Between Certain Doom and Endless Prosperity

AI continues to become more complex and sophisticated, but public policy solutions do not.

The Castle, the Cathedral, and the College

Our civilization struggles to explain why anything should command allegiance beyond preference or power; its remnants echo a grandeur now distant.