The Hidden Cost of Federal Deficit Spending

The nature of today’s debt differs significantly from prior crises.

In May, Moody’s downgraded the US government’s long-term debt instruments. This must have felt like vindication for deficit hawks who have been warning that mounting federal debt would eventually lead to a debt spiral. In short, rising concern over the size of the debt leads to rising interest rates because lenders begin to worry that they will not be paid back, at least not fully in real terms, when the Fed ends up monetizing the debt. But the increase in interest rates further increases interest payments on the debt, which, in turn, requires the issuance of yet more debt.

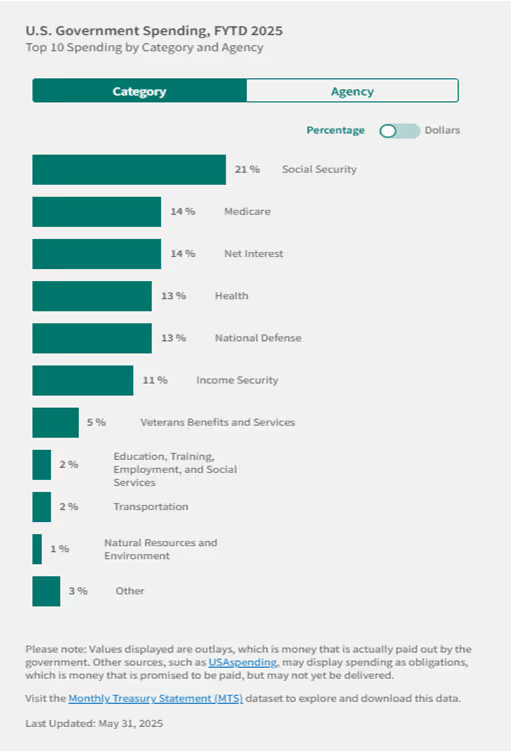

This is no longer mere theory or speculation. Net interest is now tied with Medicare for second place in federal government spending.

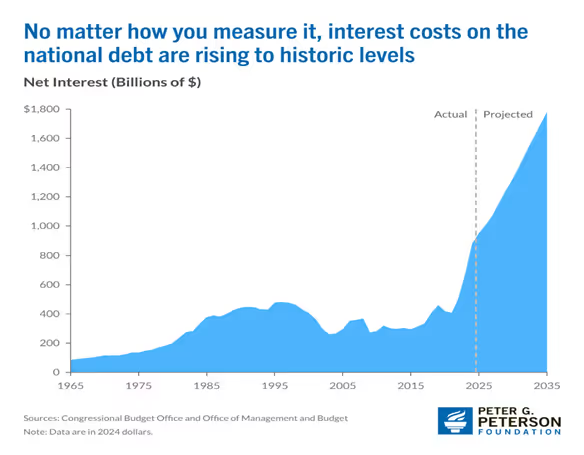

At the same time, interest on the existing debt is now the fastest growing part of the federal budget. Every day, we now spend over $2.6 billion on interest payments on the debt, and that is expected to nearly double in ten years.

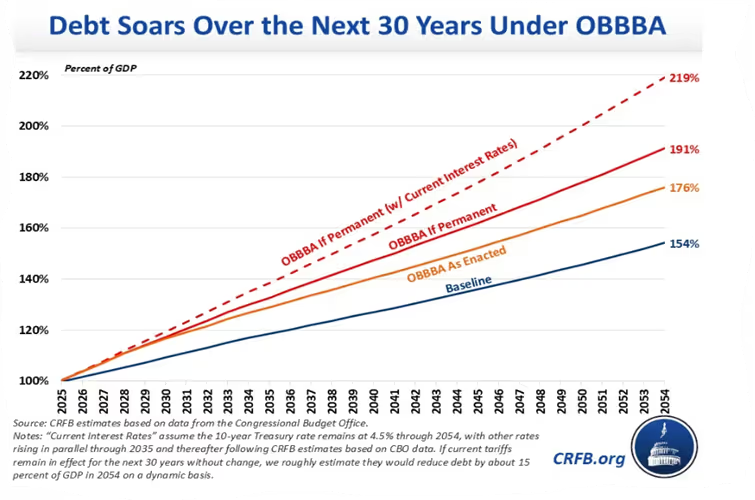

And all of that was before the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) was signed into law.

Now, according to a report from the Committee for a Responsible Budget published July 15, by FY 2054, the OBBBA will increase debt by $19 trillion as enacted, or increase debt by $32 trillion if made permanent. To put this in perspective, our current debt level is now about $37 trillion.

Here we can see the problem depicted over time (again with data from the Committee for a Responsible Budget):

But as bad as this news is, there is something very troubling about our current debt crisis that has been largely overlooked. In short, the nature of today’s debt differs significantly from prior crises. Because of this difference, voters should be putting even more pressure on elected officials to get our fiscal house in order.

Private Debt

We naturally think of the benefits of being able to borrow in terms of an individual’s life cycle. It would be foolish, for example, to wait until one has saved all the money needed for a home before buying it. This kind of borrowing is not problematic for society for two reasons.

First, it is made primarily possible by older individuals who have extra money they’d like to lend to make a better return on it. Since younger individuals expect to make plenty of money over the next 30 years or so, they can easily retire the debt they incur to buy a home now. This benefits both borrowers and lenders, and leaves everyone else unaffected.

Second, as long as the amount owed is sufficiently less than the value of the home, car, or durable good, there is little chance the loan cannot be retired by selling what the loan was used to buy. This is very different from taking out a loan to purchase something like food, which is typically consumed almost immediately after purchase.

There is another kind of private debt that is not problematic for society.

In business, debt is often issued for the purchase of capital that will be used to increase profit. Such debt is expected to be self-servicing, meaning that the increase in profit is expected to more than cover debt payments. Otherwise, why bother borrowing in the first place? And why would lenders be willing to lend?

Public Debt

The government can issue debt to finance infrastructure – things like ports, canals, highways, and so forth – which can make the private sector more productive. If such infrastructure fosters sufficient economic growth, it will produce sufficient tax revenue to cover the retirement of the debt while producing tremendous spillover benefits to the private sector.

The government can also issue debt for projects such as the purchase of land for a national park or the construction of a museum. Since these would benefit future generations, it would be ridiculous to insist that they be paid for only out of the current generation’s wealth. Such a constraint would deny future generations things they might have happily contributed to in their adulthood through higher taxes.

Finally, the government can issue debt to fund military operations or to prepare to win future wars with adversaries who might take away our freedom. If we believe our descendants would prefer to live in a free country, it is not unfair to expect them to bear some of the burden of confronting these threats.

This Time is Different

In Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff’s excellent book, This Time is Different, they reviewed eight centuries of historical evidence spanning 66 countries to show that while the details of economic crises differ, the main story is the same. In short, it is tempting to run up debt, but over time it leads to credit bubbles that, predictably, lead to financial and economic crises.

Our current debt problem is eerily similar to what happened in 2008 and prior debt-caused crises. But in this case, there is indeed something different.

The difference is the extent to which each dollar of debt translates into a dollar of unfair burden on future generations.

A rapidly growing proportion of federal spending does not fit any of the categories discussed above. With the categories above, deficit spending could be viewed as having made an investment. But increasingly, this is no longer what we are borrowing to do. We are borrowing to transfer wealth from some to others.

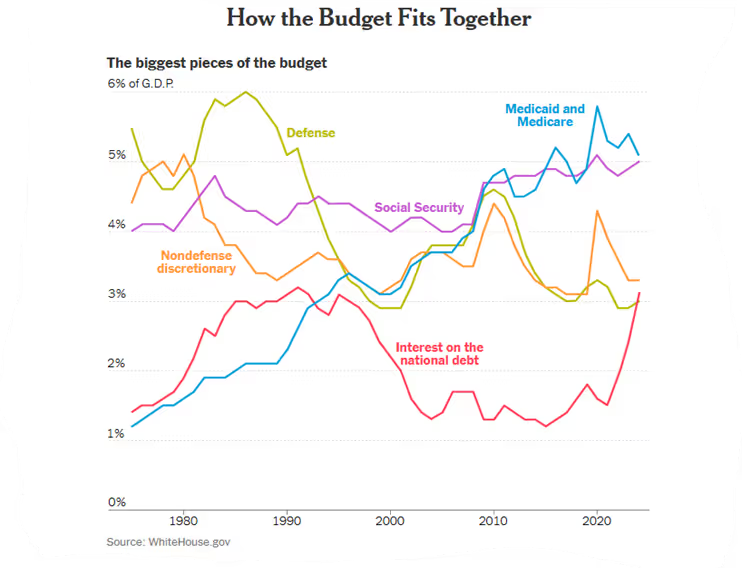

In the chart below, the largest entitlement spending programs (Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid), and interest on the national debt, are growing not just as a proportion of the federal budget, but also as a proportion of our entire economy as measured by GDP.

Why is this a problem?

Entitlement programs exist to provide social insurance that guards against suffering from material deprivation. The problem is that this is money spent on the consumption of things like water, food, shelter, utilities, and healthcare, none of which are assets that will produce benefits to citizens in the future.

Throughout most of human history, charitable redistribution of income implied that the resources needed to make the goods and services for the needy today were taken from the production of the goods and services that others in society would have otherwise consumed in the same period. In short, people gave some of their income to charitable organizations to fund programs, and to do this, they reduced their own consumption. Some consumed less in any given year, so others could consume more.

But increasingly today, entitlement spending does not come out of current consumption; it is paid for by issuing additional debt, which will be paid off in the future. This means that redistribution is occurring less and less within generations and increasingly across generations. The problem is that those on the hook had no say in the burden that is now imposed upon them.

So this money is not money that is moved around in the private sector by people benefiting from each other being at different points in their respective life cycles. And it is neither paying for capital that firms use to increase productivity, nor paying for infrastructure that makes our GDP greater and therefore increases tax revenues, nor paying for things like national parks and museums that future generations will benefit from, nor paying to preserve our way of life for future generations.

No. This is money that is just…gone. It might have been spent on noble things, of course, but the problem is that there will be poor people in the future who might need help, too.

Put another way, the debt per person in America is already over $108,000 per person. This will keep growing substantially for the foreseeable future.

But unlike previous years, the present generation won’t be choosing to make sacrifices to benefit others in their generation or to benefit future generations. The present generation will be forcing future generations to pay the bills for their consumption. It will not be to pay for winning a war, building a bridge, or developing a miracle vaccine.

This problem was nonexistent before the 40s, but now that well over 50% of our annual budget is dedicated to entitlement programs, it is already a serious problem. As unfunded liabilities mount, this problem is getting worse with each passing day. This is a much more troubling debt problem than we’ve ever experienced in American history, and addressing it by putting our fiscal house in order can now only be achieved with significant entitlement program reform.

David C. Rose is a Senior Research Fellow at AIER, an Emeritus Professor of Economics at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, and a member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

Economic Dynamism

.jpg)

Do Dynamic Societies Leave Workers Behind Culturally?

Technological change is undoubtedly raising profound metaphysical questions, and thinking clearly about them may be more consequential than ever.

The War on Disruption

The only way we can challenge stagnation is by attacking the underlying narratives. What today’s societies need is a celebration of messiness.

Unlocking Public Value: A Proposal for AI Opportunity Zones

Governments often regulate AI’s risks without measuring its rewards—AI Opportunity Zones would flip the script by granting public institutions open access to advanced systems in exchange for transparent, real-world testing that proves their value on society’s toughest challenges.

Downtowns are dying, but we know how to save them

Even those who yearn to visit or live in a walkable, dense neighborhood are not going to flock to a place surrounded by a grim urban dystopia.

The Housing Crisis

Soaring housing costs are driving young people towards socialism—only dispersed development and expanded property ownership can preserve liberal democracy.

Blocking AI’s Information Explosion Hurts Everyone

Preventing AI from performing its crucial role of providing information to the public will hinder the lives of those who need it.

Kevin Warsh’s Challenge to Fed Groupthink

Kevin Warsh understands the Fed’s mandate, respects its independence, and is willing to question comfortable assumptions when the evidence demands it.

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)