The Chief Justice's Big Idea

If Chief Justice Roberts believes agency adjudication shouldn't create broad policies or affect private rights, the carveout scope would be narrow, and the nature of agency adjudication could also change, potentially shaping the future.

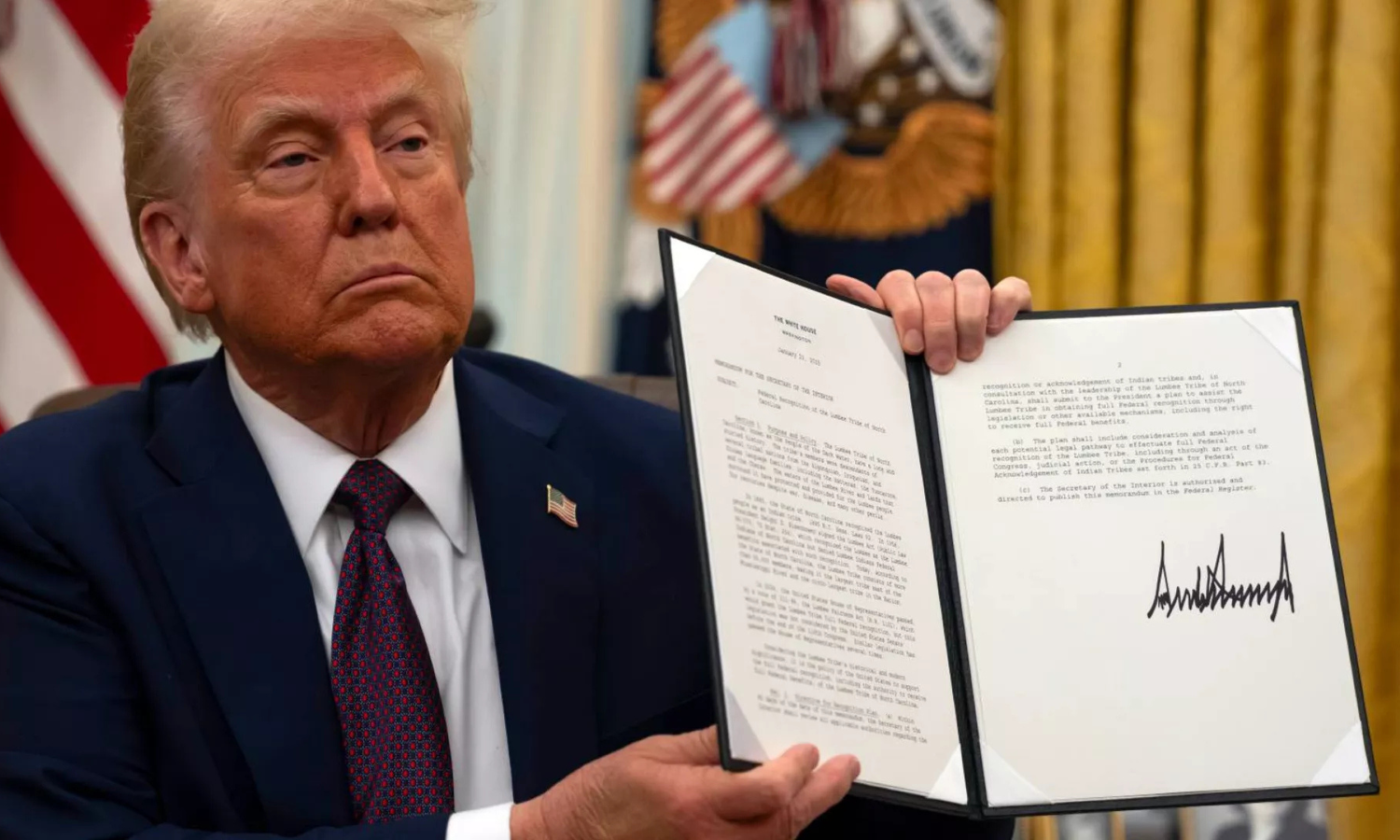

Last month, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Trump v. Slaughter, about the constitutionality of a statutory restriction on the President’s ability to fire FTC Commissioners. As I previewed here at Civitas Outlook, it is doubtful that Rebecca Slaughter will return to the FTC. After all, nothing suggests that the Court is going to hold that Humphrey’s Executor v. FTC, the 1935 decision that upheld restrictions on presidential firings, applies to today’s FTC. As Chief Justice Roberts explained during oral argument, “the one thing Seila Law”— a 2020 decision he wrote —“made pretty clear, I think, is that Humphrey's Executor is just a dried husk of whatever people used to think it was because, in the opinion itself, it described the powers of the agency it was talking about, and they’re vanishingly insignificant, have nothing to do with what the FTC looks like today.”

Both Justices Elana Kagan and Neil Gorsuch offered big ideas about what is at stake in Slaughter. Kagan, for example, said this to Solicitor General John Sauer:

Here's been the bargain over the last century, and I think it has been a bargain. Congress has given these agencies a lot, a lot of work to do that is not traditionally executive work, that is more along the lines of make rules when we issue broad delegations and do lots of adjudications that set the rules for industries and entire bodies of governance, right? And they've given all of that power to these agencies largely with it in mind that the agencies are not under the control of a single person of the President but that, indeed, Congress has a great deal of influence over them too. And if you take away a half of this bargain, you end up with just massive uncontrolled, unchecked power in the hands of the President. So the result of what you want is that the President is going to have massive unchecked, uncontrolled power not only to do traditional execution but to make law through legislative and adjudicative frameworks.

In turn, Justice Neil Gorsuch offered his own big idea:

[L]et me suggest to you that perhaps Congress has delegated some legislative power to these agencies. Let's just hypothesize that. And let's hypothesize too that this Court has taken a hands-off approach to that problem through something called the intelligible principle doctrine, which has grown increasingly toothless with time. Is the answer perhaps to reinvigorate the intelligible principle doctrine and recognize that Congress cannot delegate its legislative authority? …. I take the point that [there has been] a bargain where a lot of legislative power has moved into these agencies, but, if they're now going to be controlled by the President, it seems to me all the more imperative to do something about it.

Scholars will debate those big ideas for a long time. Kagan takes the national “bargain” to mean that Presidents should not be able to fire agency heads, thereby allowing agencies to make law with less presidential interference. Gorsuch responds that neither the President nor agencies should be making law.

With less fanfare, however, Chief Justice Roberts also hinted at a different big idea: perhaps Congress should have more flexibility to insulate adjudicators — those who decide individual matters, rather than issue broad regulations — from presidential control. During argument, he suggested that precedent upholding removal restrictions for those who exercise “significant authority but of an adjudicative nature” may be an “entirely different situation” from Humphrey’s Executor.

Some caveats are in order. First, it is perilous to read too much into oral argument. Second, even if Roberts has a big idea in mind, who knows whether a majority will go along? And third, it's also not clear what his idea entails. Putting those caveats aside, however, it's worth thinking through what it could mean to carve out adjudication from the President's constitutional power to fire.

To begin, is there a coherent basis for it? The Constitution creates three branches—and just three. Article I of the Constitution begins, “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States”; Article II begins, “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” And Article III begins, “The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” If some entity other than an Article III court (which enjoy life tenure and salary protection) is implementing federal law, that entity falls within Article II under the Constitution’s division of authority. As the Court explained in an opinion authored by the late Justice Antonin Scalia:

Agencies make rules ("Private cattle may be grazed on public lands X, Y, and Z subject to certain conditions") and conduct adjudications ("This rancher's grazing permit is revoked for violation of the conditions") and have done so since the beginning of the Republic. These activities take "legislative" and "judicial" forms, but they are exercises of — indeed, under our constitutional structure they must be exercises of — the "executive Power."

Accordingly, if Article II’s vesting of “[t]he executive Power” in the President carries with it the power to fire agency heads, it is hard to see why agency heads who promulgate rules would be treated differently from those who conduct adjudications.

One might argue that the Due Process Clause requires precisely such a distinction. If those participating in adjudication have a right to an unbiased adjudicator, then the interplay between Article II and due process may mean that adjudication and rulemaking must be different in kind.*

The problem with that response is that adjudication today can involve more than just fact finding or applying settled rules. Instead, in a 1947 decision that Justice Robert Jackson blasted for its “administrative authoritarianism,” agency adjudicators sometimes create new requirements and apply them retroactively. Jackson in dissent warned that allowing agency adjudication to be used this way blesses “conscious lawlessness,” and runs counter to the principle that “men should be governed by laws that they may ascertain and abide by, and which will guide the action of those in authority as well as of those who are subject to authority.” Not everyone agrees with Jackson’s criticisms, of course, but it is black-letter law that agencies can and do make policy through adjudication.

In a world where the Court allows agencies to make policy through adjudication rather than just rulemaking, why would the President not have the same control over both paths to policymaking? Because the Court is concerned about the consequences for liberty when agencies make policy without presidential supervision (a theme that dominates Seila Law), a decision treating adjudication differently from rulemaking could also take steps to limit what policymaking agencies may do in adjudication.

Next, how often would agencies be able to adjudicate under Roberts’ view? He did not address this issue during oral argument. Elsewhere, however, he has limited the types of issues that agencies can adjudicate. Last year, in SEC v. Jarkesy, Roberts wrote for the Court that jury trial rights apply when the SEC seeks civil penalties for alleged securities fraud. That decision necessarily limits what agency adjudicators can decide. More broadly, he believes — strongly — that Article III precludes efforts to take some matters outside of federal court. Indeed, he once accused the Court of “assign[ing] away our hard-won constitutional birthright” and ignoring a “sacred” principle by allowing Congress to take certain claims involving life, liberty, and property (often called “private rights”) out of Article III courts. Presumably, then, Robert would allow agency adjudication — without plenary control — only for some types of disputes.

Finally, there is a question about what Roberts believes the White House can do if, in the President’s view, an agency adjudicator is not faithfully applying the law. Again, he did not say at oral argument. But he often emphasizes Chief Justice Howard Taft’s analysis in a 1926 case called Myers v. United States (a case that the Court in Humphrey’s Executor took pains to minimize, but that Roberts describes as a “landmark decision”). Taft stated that that “there may be duties of a quasi-judicial character imposed on executive officers and members of executive tribunals whose decisions after hearing affect interests of individuals, the discharge of which the President cannot in a particular case properly influence or control,” but that “even in such a case” the President may still “consider the decision after its rendition as a reason for removing the officer, on the ground that the discretion regularly entrusted to that officer by statute has not been on the whole intelligently or wisely exercised.” Otherwise, Taft warned, the President could “not discharge his own constitutional duty of seeing that the laws be faithfully executed.”

It is unclear whether Roberts agrees with Taft. But if he does, and if he also believes that agency adjudication should not be used to establish sweeping new policies or impact private rights, then not only would the scope of any adjudication carveout be narrow, but the nature of agency adjudication itself would also change. If Roberts holds that view, his idea is truly significant—and it could very well shape the future.

Aaron L. Nielson is a senior fellow at the Civitas Institute and holds the Charles I. Francis Professorship in Law at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law.

Constitutionalism

Amicus Brief: Hon. William P. Barr and Hon. Michael B. Mukasey in Support of Petitioners

Former AGs Barr and Mukasey Cite Civitas in a SCOTUS Brief

Rational Judicial Review: Constitutions as Power-sharing Agreements, Secession, and the Problem of Dred Scott

Judicial review and originalism serve as valuable commitment mechanisms to enforce future compliance with a political bargain.

Supreme Court showdown exposes shaky case against birthright citizenship

Supreme Court will hear challenges to Trump's order ending birthright citizenship, testing the 14th Amendment's guarantee for babies born in America.

Slavery and the Republic

As America begins to celebrate its semiquincentennial, much ink has been spilled questioning whether that event is worth commemorating at all. Joseph Ellis’s The Great Contradiction could not be timelier.

Two Hails For The Chief’s NDA

Instead of trying to futilely plug the dam to stop leaks, the Court should release a safety valve.

.avif)

.avif)