Boosting Technological and Research Collaboration among Latin America, the Caribbean, and the United States

Latin America and the Caribbean must strengthen scientific collaboration and attract U.S. talent marginalized by Trump 2.0 policies, leveraging this opportunity to boost innovation, sustainability, and regional development.

Technological intelligence is the process of collecting, analyzing, and understanding information about artifacts, machines, systems, and processes—often documented in patents and scientific research—to evaluate how they work, how they can be improved, and how they might be combined to meet new challenges. It is one of the most powerful tools for building the future.

At their core, technologies are assemblies of artifacts; they are objects crafted with purpose and technical skill. A Neolithic spear, for example, is a sharpened stone, bound with fiber to a carved wooden shaft. It was an early form of technology, created to perform a specific function. Today, we have far more complex systems, but the principles of technological assembly and purpose remain.

As technological forecasting analysts, we leverage computing power to examine vast datasets, identify innovation trajectories, and forecast emerging trends. This work relies not only on data but also on a profound understanding of science and technology policy, particularly the research collaboration networks that connect researchers across borders and disciplines. Despite the projected data based on statistical trends and stochastic scenarios, political decisions can lead to other dynamics for technological advancements.

Since the end of World War II, the United States has been the global model for scientific and technological policy. It pioneered megaprojects—such as the Manhattan Project—that attracted the world’s best talent. The U.S. also formalized technological forecasting through initiatives like the U.S. Air Force's 1945 report “Toward New Horizons”, which was a foundational inventory of future-oriented technologies. The establishment in 1950 of the National Science Foundation (N.S.F.), under the guidance of figures like Chester Barnard, one of the most influential management thinkers in history, marked another milestone. The U.S. government also invested in predictive tools and methodologies, including the Delphi method and foresight studies at the RAND Corporation. In 1972, Congress established the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA), which served as a key advisory body until its closure in 1995. Since then, the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), housed in the Executive Office of the President, has taken the lead on science foresight and advised on technological trends and national innovation strategy.

In Latin America and the Caribbean (L.A.C.), the adoption of technological foresight came later, supported by institutions like CEPAL (ECLAC), UNESCO, the Inter-American Development Bank (I.D.B.), and the Ibero-American Program for Science and Technology for Development (CYTED). Notable regional efforts emerged in the early 2000s, including Brazil’s CGEE (Center for Management and Strategic Studies), Mexico’s CONACYT, and Colombia’s National Foresight Program, which was led by Javier Medina, now Deputy Executive Secretary at ECLAC.

President Donald Trump began his second administration by announcing “Stargate”: a massive new project in partnership with tech giants like OpenAI, Oracle, MGX, and SoftBank. With a $500 billion investment, the project aims to counter China’s DeepSeek and dominate global leadership in artificial intelligence and quantum computing. Moreover, Trump signed a letter to OSTP Director Michael Kratsios outlining a roadmap for the Golden Age of American Innovation, which is based on artificial intelligence, quantum information science, and nuclear technology. Trump has also pledged fewer regulatory barriers and stronger support for private space technology—led by his allies Elon Musk (SpaceX) and Jeff Bezos (Blue Origin)—including the dismantling of the White House National Space Council. Meanwhile, he is likely to sideline critical areas of global scientific concern, such as climate change and public health.

Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Climate Agreement and the World Health Organization. He declared an energy emergency to prioritize oil and gas, bolstering U.S. geopolitical influence but ignoring AI’s environmental costs and the resource-intensive demands of data mining and computation. He appointed prominent anti-vaccine activist Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to head the Department of Health and Human Services and halted federal funding for virology research. Moreover, the National Institutes of Health bans American funding to research partners abroad. These moves threaten the foundations of international scientific cooperation, not only due to erratic policy shifts but also because of a xenophobic posture that ignores immigrants’ enormous contribution to American innovation.

L.A.C. has long depended on scientific collaboration with the U.S. The Scopus database, spanning from 1994 to 2024, reveals nearly three million publications from L.A.C.; approximately thirteen percent—approximately 400,000 documents—of those were co-authored with U.S. institutions. This figure dwarfs collaboration with Spain (184,000 publications) and nearly equals the combined total with Spain, France, and the U.K. (14 percent).

The most collaborative fields include medicine (19 percent), agricultural and biological sciences (11 percent), physics and astronomy (9 percent), and biochemistry, genetics, and molecular biology (8.5 percent). In strategic areas for new technological developments like immunology, microbiology, and computer science, however, collaboration remains low (around 3.5 percent each).

If Trump 2.0 follows his previous trajectory, these low-collaboration fields—along with biotechnology, physics, and space science—may suffer further setbacks. However, L.A.C. has a rare opportunity: by increasing science investment and adopting an open-door strategy, the region could attract talent that Trump-era policies marginalize.

The European Commission, in partnership with leading universities, has already launched an initiative offering academic freedom and research opportunities to U.S. scholars affected by political interference, particularly in areas such as immunology, climate science, and the social sciences. L.A.C. should follow suit. With coordinated efforts—and institutions like CYTED and ECLAC—regional governments could create fellowships or calls for proposals that provide U.S.-based researchers with the freedom to pursue their work in the region. This would not only strengthen the L.A.C. scientific and technological ecosystem but also offer the region an opportunity to create a haven for global scientific progress, improving neglected research areas crucial for addressing sustainability and climate change, and pursuing better healthcare technologies, capitalizing on the region's broad biodiversity.

Luis Antonio Orozco, Ph.D., is a full professor at Universidad Externado de Colombia and a member of BeLatin. He is the associate editor of the Journal of Management History of Emerald Publishing, and Cogent Business & Management of Taylor & Francis, and a member of the editorial board in Palgrave Debates in Business History – Springer Nature.

Economic Dynamism

The Causal Effect of News on Inflation Expectations

This paper studies the response of household inflation expectations to television news coverage of inflation.

.avif)

The Rise of Inflation Targeting

This paper discusses the interactions between politics and economic ideas leading to the adoption of inflation targeting in the United States.

Why Can't the Middle Class Invest Like Mitt Romney?

Why can’t middle-income Americans pay effectively no taxes on investments like the wealthy do?

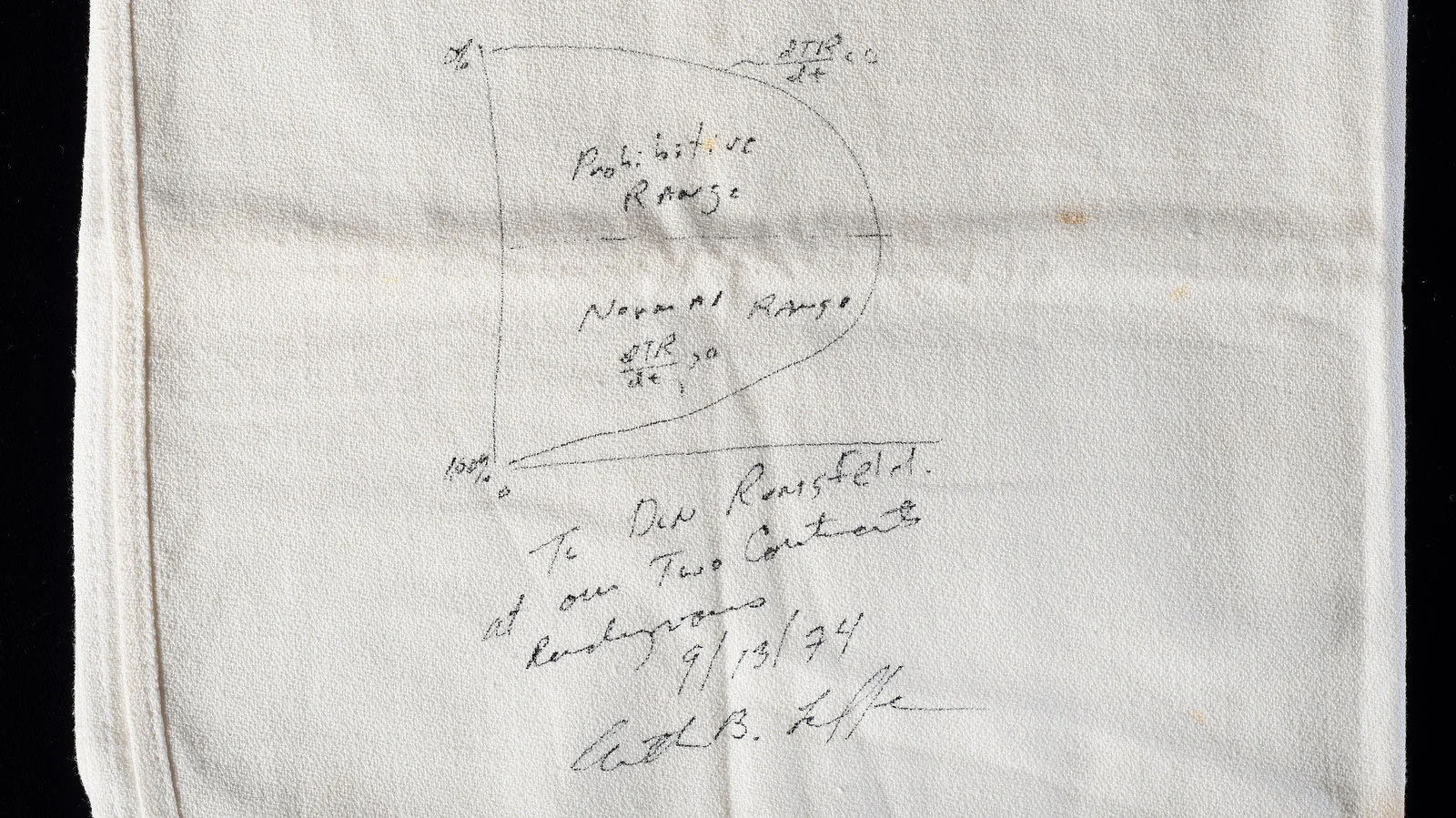

The Revenge of the Supply-Siders

Trump would do well to heed his supply-side advisers again and avoid the populist Keynesian shortcuts of stimulus checks or easy money.

.jpg)

.jpg)