A New Consensus in Latin America

The new consensus in Latin America must counter the Bolivarian movement's criminal and ideological influence, stressing the need for stronger U.S. engagement and defense of democratic, market-based values.

Latin America’s economic and political path became significantly influenced by the Washington Consensus during its implementation. The period from 1980 to 2000 saw Latin American countries implementing institutional constitutional reforms under the guidance of the United States through multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. The changes brought about by these reforms enabled Chile and Peru to experience some macroeconomic development, but the results were temporary and limited to specific areas.

The Consensus was inherently constrained: its implementation focused on "macro" (first-level) reforms but lacked a complementary set of "micro" (second-level) reforms related to regulation, taxation, labor, and other areas where even the United States has yet to present a coherent policy framework. Moreover, external forces undermined these reforms: a counter-consensus—embodied by the Bolivarian movement (influenced by the Castro-Chávez alliance)—emerged and advanced an alternative model.

In the region, the Bolivarian movement gained support from China and Russia as it advanced its alternative development model, which promoted extensive government intervention, expanded “social rights”, limited private sector participation, and diminished openness to the global economy, particularly towards the United States and Europe. The ideological rivalry between the two systems created a deep impact on how countries designed their constitutional structures. All countries in the region adopted a mixed model, which combined elements from both systems by implementing, to some extent, the Washington Consensus principles of macroeconomic stability, foreign trade openness, and property rights, alongside the recognition of more “social rights” and economic government intervention mechanisms, reflecting the counter-Bolivarian consensus.

As a result, the Washington Consensus was not widely adopted in countries such as Venezuela, Ecuador, and Bolivia. In contrast, others shifted their economic policies from market-oriented to socially driven ones with disastrous consequences: For instance, since 2014, Chile and Peru have faced economic stagnation because of rising state control through regulatory measures and social welfare initiatives.

It can be argued that the presence of ideological diversity regarding the state's role in the economy is not problematic. Western democracies frequently engage in debates about this very issue. Even in the US and Western societies in general, there is an ongoing dispute about the role of the state in the economy. Some European nations can be labelled socialist, while cultural Marxism has deeply penetrated the U.S. through elite academic institutions.

The complexity of the situation increases when examining the combined influence methods of China and Russia, along with the true nature of the Bolivarian movement. During the past several decades, China and Russia supplied billions in financial resources and military equipment to Cuba and Venezuela through loans and assistance programs. These regimes operate in ways that mimic criminal gangs more than conventional governments as they work to ideologically mold the region while attacking democracy and promoting illegal operations, including drug smuggling, corruption, human trafficking, and institutional penetrations.

The 2019 Chilean uprising was not entirely spontaneous, as Bolivarian agents and funding played a role in influencing it. In 2021, Peru almost lost the country to a political group that maintained connections with both terrorism and narco-trafficking. The region has been infiltrated by Bolivarian operatives posing as diplomats, medical personnel, and gang affiliates. Extortion activities are rapidly increasing throughout the region, which negatively impacts both private property development and entrepreneurial activities. In addition to Cuba and Venezuela, Mexico and Bolivia have transformed into narco-states, while Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru face equivalent threats.

The implications for the United States are self-evident: human and drug trafficking, as well as money laundering, espionage, institutional corruption, and culture war through media and academia control. From a business perspective, Russia and especially China do not operate under conventional rules. For them, commerce is part of a broader strategic objective aimed at undermining U.S. and Western influence. Their agenda in Latin America, facilitated by the Bolivarian movement, is backed by cultural influence from media and academia, along with trade and infrastructure investment that creates substantial barriers to both resistance and public discussion on the matter.

During Biden’s administration, U.S. policy appeared passive, even compromised, in the face of these developments. For instance, when China acquired the remaining 50 percent stake in Peru’s electric distribution sector and began construction of a mega-port in Chancay (near Lima), the U.S. merely expressed “concern”—a response that highlights a lack of strategic urgency. These infrastructure projects also serve strategic purposes by enhancing Chinese regional influence and military capabilities.

The Bolivarian movement represents a deeply destabilizing and disruptive force in Latin America while simultaneously posing a growing risk to the United States. China firmly upholds its position as the leading supporter of this political movement. While Latin America must ultimately follow its path and take responsibility for its future, it is equally clear that the region remains a strategic location for China to exert influence against the United States.

Often, the U.S. and China/Russia are viewed in Latin America as equivalent superpowers with divergent but equally self-interested goals. The narrative contains some truth, yet fails to recognize a fundamental difference: The U.S. represents a benevolent force in the world as it stands for democracy and free markets, ideals and values that are exceptional, and that impose a great responsibility that it must fulfill.

It is time for a new Consensus—one that powerfully confronts and combats the criminal and ideological influence of the Bolivarian movement.

Oscar Sumar is the Pro Vice-Chancellor for Academic Affairs, Universidad Científica del Sur, Peru. Non-resident fellow of the Public Law and Policy Program, Berkeley Law. Co-Chair of BeLatin. His most recent book, titled Regulatory Countertrend, deals with the regulatory state and evaluations of economic regulation.

Economic Dynamism

The Causal Effect of News on Inflation Expectations

This paper studies the response of household inflation expectations to television news coverage of inflation.

.avif)

The Rise of Inflation Targeting

This paper discusses the interactions between politics and economic ideas leading to the adoption of inflation targeting in the United States.

Why Can't the Middle Class Invest Like Mitt Romney?

Why can’t middle-income Americans pay effectively no taxes on investments like the wealthy do?

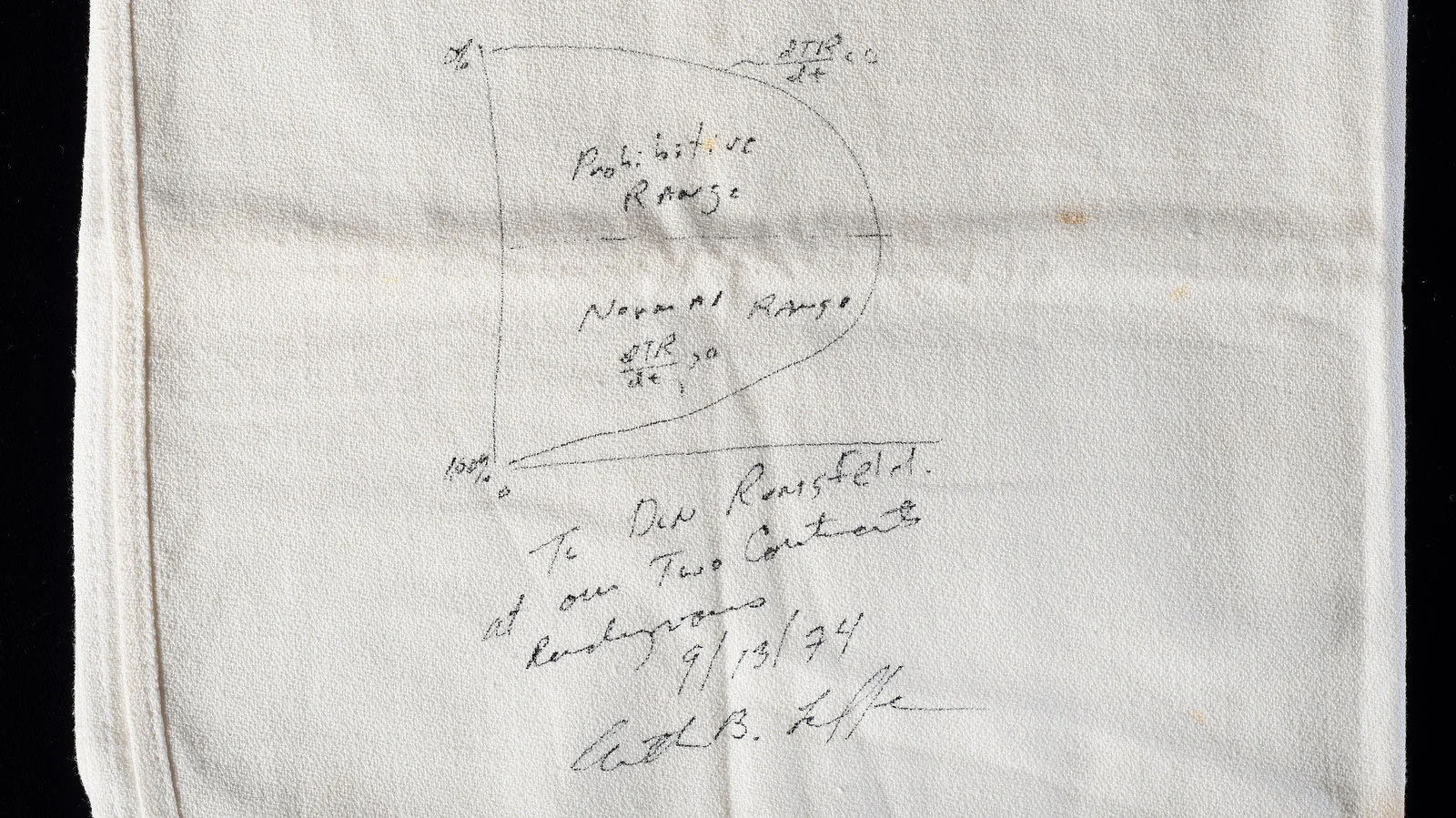

The Revenge of the Supply-Siders

Trump would do well to heed his supply-side advisers again and avoid the populist Keynesian shortcuts of stimulus checks or easy money.

.jpg)

.jpg)