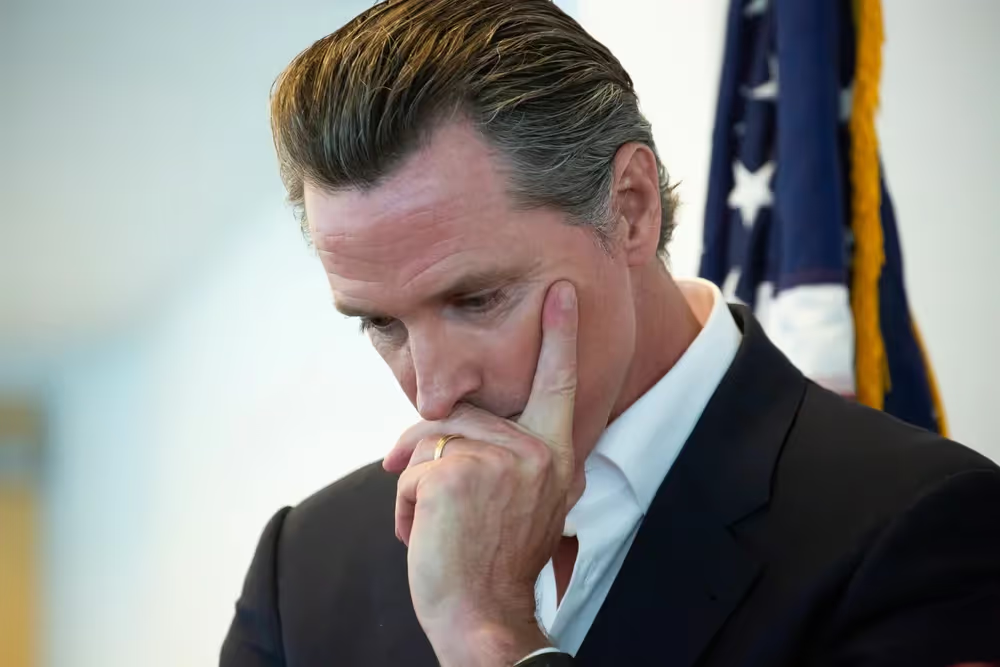

Governor Newsom Is Committing Constitutional Malpractice

California officials will soon learn in court, just as they are learning on the streets, that the California National Guard reports to President Trump.

A governor with ambitions wants to challenge the President’s use of his state’s National Guard during a crisis. He sues on the ground that the White House needs the governor’s permission to deploy the National Guard. Although the governor’s legal stunt fails badly, he goes on to win his party’s presidential nomination.

Gavin Newsom today? Perhaps. But the facts above describe the Michael Dukakis 1988 playbook – a text rarely consulted by political winners. To be sure, the circumstances are very different. The Massachusetts governor (joined by other Democratic governors) went to court to challenge Ronald Reagan’s deployment of National Guard troops to Central America for training. Today, by contrast, Newsom is suing the federal government for calling up the California National Guard to quell rioters who have attacked ICE facilities and officers in Los Angeles.

But the results will be identical. In Perpich v. Department of Defense (1990), the Supreme Court rejected the Dukakis claim that governors had a veto over presidential orders to the National Guard. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution declares that Congress has the power “to provide for calling for the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections, and repel Invasion.” It also provides that Congress shall “provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the Militia,” which evolved into the National Guard, “and for governing” those units called into federal service. Justice John Paul Stevens (no conservative he) wrote for a unanimous Supreme Court that Congress held plenary authority over the National Guard, could set the conditions for calling them into national service, and that once federalized, they became part of the regular army. The National Guard ultimately fell under the control of President Reagan, not Governor Dukakis.

So too, California officials will soon learn in court, just as they are learning on the streets, that the California National Guard reports to President Trump, not Governor Newsom. President Trump has multiple grounds on which to call out the U.S. Armed Forces to put down the riots. There is a long and important tradition in our country, expressed in the Posse Comitatus Act, against using the military domestically. The PCA prohibits the use of the military “to execute the laws,” except when “expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress. The traditional bar on the use of the military domestically, therefore, has important exceptions, such as protecting the national government and breaking up resistance to federal law, which the Constitution itself and statute authorizes. The Supremacy Clause declares a fundamental constitutional principle that federal law is superior to state law; California’s officials and residents have no right to block the enforcement of federal immigration policy, no matter how much they disagree with it.

First, Congress has used the power over the state militia upheld in Perpich to delegate to the President the authority to call out the National Guard. Critics such as Newsom have focused on the first two cases for which Congress provided: “invasion” or “rebellion.” They imply that Trump has exaggerated conditions on the ground in Los Angeles to introduce the military into cities to expand his own power. Newsom, for example, declared that “these are the acts of a dictator, not a President," and dared Trump to arrest him.

But these opponents conveniently ignore the third ground to call out the National Guard. Congress allows the President to federalize the National Guard when he “is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.” It seems evident from the scenes of violence in Los Angeles that protesters seek to stop the enforcement of federal immigration law. Protesters have launched riots to stop ICE and DHS agents from carrying out their duties and have sought to blockade and enter federal buildings. They have attempted to shut down freeways and impede traffic, and have even attacked federal buildings in nearby counties. Television scenes show obvious efforts to stop the federal government from apprehending and removing illegal aliens under its immigration laws.

Second, Presidents have the authority to protect the federal government and its officers from attack. To be sure, the primary responsibility for criminal law enforcement lies with state and local officials. Controlling rioters, restoring law and order to the city streets, and prosecuting offenders fall within the “police powers” exercised by the states and recognized by the Constitution’s Tenth Amendment. While the federal government plays a significant role in criminal justice, the Supreme Court has emphasized that federal authority should primarily focus on interstate crimes. Thus, United States v. Lopez (1995) rejected the idea of “a general federal police power” and noted that “in areas such as criminal law enforcement … States historically have been sovereign.”

But this is not yet a case of federal intervention to restore law and order. Los Angeles 2025 has not yet collapsed into the chaos of Los Angeles 1992. In 2025, the administration is not replacing the states' responsibility to maintain basic public safety. Instead, Trump is enforcing federal immigration law; in fact, the Supreme Court in Arizona v. United States (2012) has declared that only federal officials may carry out immigration law and policy. President Trump has the authority to deploy troops to protect federal law enforcement officers. In 1971, William Rehnquist, as assistant attorney general for the office of legal counsel at the Department of Justice, declared that the President could use troops in response to attacks on federal employees and agencies. DOJ, he wrote, had long taken the position that the Posse Comitatus Act “does not impair the President’s inherent authority to use troops for the protection of federal property and federal functions.” This conclusion, he argued, is “supported by the historic and judicial recognition of the President’s inherent powers to use troops to protect federal property and functions as a necessary adjunct of his constitutional duties under Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution.”

Future-Chief Justice Rehnquist did not conjure this presidential power out of thin air. The Supreme Court had already long recognized the authority. In In re Neagle (1890), the Supreme Court addressed the use of force by a federal marshal assigned to protect Supreme Court Justice Stephen Field. Field was traveling in his native California when a former rival assaulted him; the marshal shot and killed the attacker. Even though no law authorized federal officers to use force as bodyguards, the Court ordered California to free the federal marshal:

We hold it to be an incontrovertible principle that the government of the United States may, by means of physical force, exercised through its official agents, execute on every foot of American soil the powers and functions that belong to it. This necessarily involves the power to command obedience to its laws, and hence the power to keep the peace.

Because of supremacy over the matters entrusted to it by the Constitution, the Court reasoned, the President had the power to protect the security of the federal officials who carried it out. “We cannot doubt the power of the president to take measures for the protection of a judge of one of the courts of the United States who, while in the discharge of the duties of his office, is threatened with a personal attack which may probably result in his death,” Justice Miller wrote for the Court. Miller’s logic extends beyond the judiciary to encompass the entire federal government.

In the face of late nineteenth century labor strife, the Supreme Court expanded Neagle to include not just the protection of federal personnel, but also their functions. In 1894, union organizers and workers sought to block all trains using Pullman railcars, effectively halting all trains nationwide. President Grover Cleveland ordered U.S. troops to prevent the obstruction of trains carrying the mail; the Army broke the strike, and Eugene Debs was arrested and convicted (despite the best efforts of his defense counsel, Clarence Darrow). In In re Debs (1895), the Court refused to grant Debs a writ of habeas corpus. It declared:

The entire strength of the nation may be used to enforce in any part of the land the full and free exercise of all national powers and the security of all rights intrusted by the constitution to its care. The strong arm of the national government may be put forth to brush away all obstructions to the freedom of interstate commerce or the transportation of the mails.

The federal government could use even the military, if necessary. “If the emergency arises, the army of the nation, and all its militia, are at the service of the nation, to compel obedience to its laws,” Justice Brewer concluded.

Under Neagle and Debs, the President can use the military to protect federal facilities and the federal personnel carrying out legitimate federal functions. Presidents have the further authority to use federal troops to execute the law in the face of organized resistance. Going back to the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion, chief executives since George Washington have deployed troops to break up groups that resist federal law enforcement. At the outbreak of the Civil War President Lincoln carefully limited the deployment of federal forces against the Confederacy to federal installations and the execution of federal law. This presidential authority comes directly from the Constitution. The President has the constitutional responsibility to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” and, as Chief Executive, the President protects the integrity of the government itself. As the Court has said that immigration is a purely federal function, there can be little doubt that ICE and DHS agents are engaged in valid law enforcement operations. And if Trump’s orders remain limited to protecting those agents, his authority falls within the constitutional authority to protect the national government.

Third, President Trump could expand the military’s mission beyond protecting the federal government to include law enforcement. Congress has amplified presidential power by granting the executive the authority to intervene, even without the agreement of governors, under the Insurrection Act of 1807. For the Act to apply, disorder must rise to the level of an “insurrection” that “opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or impedes the course of justice under those laws.” Under this law, Dwight Eisenhower sent the armed forces into Little Rock when Arkansas Governor Orville Faubus refused to desegregate the city’s public schools. President George H.W. Bush invoked the law, at Governor Pete Wilson’s request, to send troops to restore order in Los Angeles during the 1992 Rodney King riots. These precedents would justify the invocation of the Insurrection Act to end the rioting in Los Angeles, should disorder spread beyond the attacks on ICE and DHS officers and facilities to a broader collapse of law and order.

Under Supreme Court case law, the courts would defer to the President on whether the circumstances justified triggering the Insurrection Act. This approach reflects the appropriate institutional roles that the Constitution assigns to the executive and the judiciary. Courts have little ability to judge whether opposition to federal policy has coalesced into organized resistance to federal law enforcement. Governor Newsom’s suit asks courts to overthrow this traditional respect for the responsibilities of the elected branches of government. A federal district judge might be found to rule against Trump, but the Supreme Court would likely intervene to prevent judges from extending their power beyond its proper ambit. A judge may find that the facts on the ground do not constitute an obstacle to enforcing federal law that would justify the President’s power to protect or the use of the Insurrection Act. But judges should leave opponents to the mechanisms for opposition established by the Framers: Congress’s authority over funding, legislation, and oversight; the national political system, including political parties; and ultimately, impeachment.

Governor Newsom and his fellow Trump critics cannot claim that Presidents lack the authority to call out the troops to protect the national government and enforce federal law. There is no racial or social justice coloration to these laws. Presidents have used these same authorities to desegregate southern schools in the 1950s after Brown v. Board of Education and to protect civil rights protesters in the 1960s. Congress banned the use of troops for law enforcement in the PCA because of the success of the South in ending Reconstruction, one of Washington, D.C.’s most significant failures. If critics want the federal government to have the power to enforce civil rights laws against recalcitrant states, they also must concede to President Trump the power to enforce immigration laws against rioters in Los Angeles.

Governor Newsom, however, may have little regard for the law and the facts. He may espy, as did Michael Dukakis, a political opportunity to challenge President Trump. He may seek to make himself the leader of the opposition. But he should take another look at the Dukakis playbook to see how 1988 turned out. Dukakis went on to lose in a near landslide – 426 to 111 electoral votes – and the Supreme Court rejected his constitutional challenge to President Reagan 9-0. If Newsom maintains his current case, he will be lucky even to have a chance to run as a presidential candidate four decades later.

John Yoo is a senior research fellow at the Civitas Institute, and a distinguished visiting professor at the School of Civic Leadership at the University of Texas at Austin. He is also the Emanuel Heller Professor of Law at the University of California at Berkeley where he supervises the Public Law and Policy Program among other programs at Berkeley Law. Concurrently, he is a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Constitutionalism

Amicus Brief: Hon. William P. Barr and Hon. Michael B. Mukasey in Support of Petitioners

Former AGs Barr and Mukasey Cite Civitas in a SCOTUS Brief

Rational Judicial Review: Constitutions as Power-sharing Agreements, Secession, and the Problem of Dred Scott

Judicial review and originalism serve as valuable commitment mechanisms to enforce future compliance with a political bargain.

Supreme Court showdown exposes shaky case against birthright citizenship

Supreme Court will hear challenges to Trump's order ending birthright citizenship, testing the 14th Amendment's guarantee for babies born in America.

Charles Sumner’s Harmony with the Declaration

Sumner used the Declaration to increase the Constitution’s pursuit of forming a more perfect union.

Men and Women: Equal but Beautifully Distinct

Powerful interests are being served, but they are not those of young women competing in adolescent sports, or the larger need of our society to know that its words, laws, and public speech conform to the reality that we did not summon into being.

.avif)

.avif)