A Nobel Prize for Innovation, Dynamism, and Creative Destruction

The 2025 Nobel Laureates, Philippe Aghion, Peter Howitt, and Joel Mokyr, found that economic growth comes from dynamism, creative destruction, and the open exchange of ideas.

When the Royal Swedish Academy announced that this year’s Nobel Prize in Economics would go to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt “for their analysis of innovation-led growth,” it reaffirmed a fundamental truth of capitalism: prosperity comes not from stability, but from creative destruction—the process of competition and renewal that economist Joseph Schumpeter highlighted nearly a century ago.

Joel Mokyr, the Northwestern University economic historian, has spent a career asking why modern economic growth began when and where it did. Why did sustained economic growth first emerge in Britain and the Netherlands around 1750, after millennia of stagnation elsewhere? His answer: a revolution in ideas.

In Mokyr's account, the Industrial Revolution was the result of a cultural shift — the rise of what he terms the Republic of Letters: open inquiry, merit-based debate, and trust in scientific reasoning. Previously, artisans kept secrets and rulers guarded monopolies. Breaking these barriers created free entry into the market for ideas. Mokyr classifies ideas into "propositional knowledge" (the “what”) — scientific understanding of how nature works and "prescriptive knowledge" (the “how”) — the practical know-how of engineers and artisans.

Mokyr's point is that economic progress depends less on machines or government programs than on an open society that rewards curiosity and tolerates dissent. For Mokyr, economic freedom and intellectual freedom are two sides of the same coin. Political fragmentation (that is, the presence of a large number of competing European states) made it possible for innovative ideas to thrive, as entrepreneurs, innovators, and ideologues could easily flee to a neighboring state if their own state tried to suppress their ideas and activities. Technology like the printing press played a pivotal role in the exchange of ideas, and constraints on the executive through the development of parliamentary bodies prevented rulers from halting innovation.

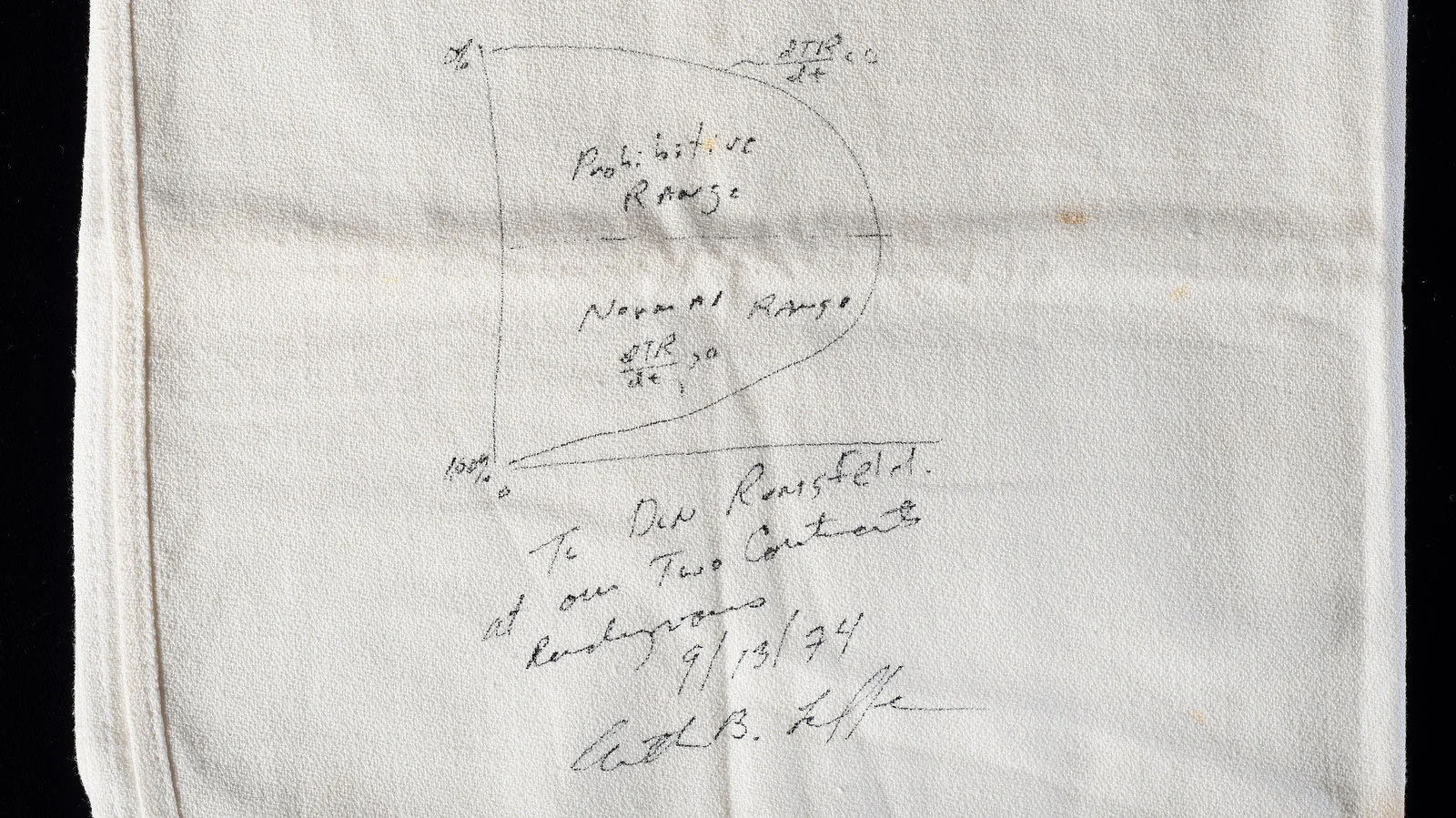

If Mokyr provided the history, Aghion and Howitt provided the model. Their seminal 1992 paper, "A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction", transformed macroeconomics by introducing "endogenous growth theory". In their framework, entrepreneurs introduce new technologies that render old ones obsolete. Innovation yields temporary profits, but those rents are eroded as future innovators compete them away. Growth is thus a dynamic process of experimentation, entry, and replacement.

Their theory replaced the old "exogenous" growth theory view developed by Robert Solow, which treated technological progress as a fixed, random process. Aghion and Howitt showed that people generate ideas that lead to broad-based innovation, which can then spread. Having more people and a larger population means there's a greater chance of ideas that further drive innovation, growth, and sustenance, a view contrary to those who fear overpopulation, such as Thomas Malthus and Paul Ehrlich.

Together, these laureates remind us that growth requires the freedom to challenge, disrupt, and sometimes fail. The market’s churn is not a flaw but its defining virtue. As Schumpeter put it, capitalism “never can be stationary.” Yet he also warned that its very success might breed the complacency and bureaucratization that ultimately stifle it.

That warning feels prescient today. In Western Europe, Canada, and Japan, business formation and economic growth have been slowing, market concentration is rising, and political hostility toward “disruption” is spreading. Some policymakers dream of industrial planning and demonstrate hostility to tech innovation, such as generative AI, in its infancy. They forget it's the decentralized trial-and-error process that drives growth.

But creative destruction cannot be replaced by government committees. Attempts to protect incumbents or “strategically guide” innovation risk entrenching mediocrity. A dynamic economy, by contrast, depends on permissionless experimentation, where entrepreneurs can enter, fail, and try again without asking the state’s permission. Policies like Europe's employment protection laws work against this process.

The policy implications of this Nobel are clear. It can be difficult for governments to engineer innovation; their efforts are best employed in protecting the ecosystem that allows ideas to spread and enables economic growth. That means strong property rights, open markets, light regulation, and a culture that celebrates risk rather than punishes it.

It also means avoiding the temptation to pick winners. Ensuring losers can fail quickly and new entrants can rise is key to a dynamic economy. Aghion’s later work shows that competition and innovation are complements, not opposites. Shielding firms from rivals breeds complacency; exposure to competition forces them to adapt.

At a time when confidence in markets is declining, the Nobel Committee’s decision quietly champions economic freedom. Growth doesn’t stem from government plans or five-year strategies. It originates from the unpredictable, decentralized innovation of individuals pursuing their own ideas and ambitions.

Joel Mokyr argued that the Enlightenment’s culture of openness enabled sustained economic progress. Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt showed why that process of creative destruction remains essential for growth today. Together, they remind us that capitalism’s genius lies not in efficiency but in evolution—its endless capacity to learn, adapt, and reinvent itself.

As Schumpeter might have said, this year’s Nobel celebrates not equilibrium but dynamism — the restless churn that keeps humanity and the economy moving forward, helping to lift many out of poverty as its chief byproduct. For those who believe in economic freedom, enterprise, defeating poverty, and the power of ideas, it is a well-deserved prize indeed.

Jonathan Hartley is a research fellow at the Civitas Institute, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and podcast host of Capitalism and Freedom in the 21st Century at the Hoover Institution.

Economic Dynamism

The Causal Effect of News on Inflation Expectations

This paper studies the response of household inflation expectations to television news coverage of inflation.

.avif)

The Rise of Inflation Targeting

This paper discusses the interactions between politics and economic ideas leading to the adoption of inflation targeting in the United States.

The Housing Crisis

Soaring housing costs are driving young people towards socialism—only dispersed development and expanded property ownership can preserve liberal democracy.

.jpeg)

America Needs a Transcontinental Railroad

A proposed merger of Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern would foster efficiencies, but opponents say the deal would kill competition.

The Poverty of Vanceonomics

At the core of Vanceonomics is a preferential option for government intervention.

Entrepreneurial Freedom in the Age of AI

The AI economy can lead to a more inclusive economy that permits people the freedom to choose when they work, what they work on, and who they work for.

.jpg)

.jpg)