A National Day of Gratitude

I recall my family’s first Thanksgiving in America six decades ago. Our little band had arrived from Communist Romania with little more than our clothes, none of us except my multilingual father speaking English.

The salutary effects of thankfulness have been known for millennia. Enhanced through prayers, celebrations, and rituals, gratitude nourishes the soul; we emerge refreshed, almost as if reborn. As the to-do lists streaming through our brains are mercifully interrupted, we are able to remember what we owe to one another and to a universe too complex for any mind to fathom. We can reconnect with those we love who are too far, geographically or emotionally, and with those we have lost. We especially reconnect with those close to us: we hug and hope to stay healthy, to love them a little longer. A national holiday like Thanksgiving embodies this, but it is so much more.

Its origin in America may be traced to 1619, when on December 13, 38 settlers landed in Virginia on land granted by the British Crown to the Berkeley Company. They immediately held a service as required by the Company’s charter, which “ordaine[d] that the day of our ships arrival at the place assigned for plantation in the land of Virginia shall be yearly and perpetually keept [sic] holy as a day of thanksgiving to Almighty God.” The site would become the ancestral property of the Harrisons, home to two of America’s future presidents. The idea of a recurring day of gratitude to God was indeed a proto root. Having been mandated by the King, however, it wasn’t quite ours.

Seventeen days later, on December 30, the Pilgrims would arrive aboard the Mayflower. It was a hard landing, followed by a brutal winter that took many by starvation and disease. Not until 1621 were the Pilgrims able to hold their own Thanksgiving, in a manner that emulated the Old Testament tradition of birkat ha-gomel, the Jewish prayer of gratitude. Over the course of three days, 52 colonists, joined by 90 Wampanoag men, enjoyed a sumptuous feast. Like others of a similar kind elsewhere in the colonies, it would later become the prototypical holiday fare.

But it would take another century and a half for Thanksgiving to become a national holiday. Before that, on November 1, 1777, the first Continental Congress would issue a National Proclamation of Thanksgiving occasioned by the Continental Army’s victory at Saratoga. Penned initially by super-propagandist Samuel Adams, the proclamation urged “the legislative or executive powers of these United States, to set apart Thursday, the 18th day of December next, for solemn thanksgiving and praise.”

Five excruciating, miraculous years later, the Revolutionary War ended in victory. Another Proclamation could be issued on November 5, 1782, to mark the Treaty of Paris and acknowledge American independence. But the most important national proclamation, the first to be issued under the U.S. Constitution, had to await another seven years.

On October 3, 1789, in response to a resolution offered by New Jersey Congressman Elias Boudinot, President George Washington issued a Thanksgiving Proclamation that invited “the People of the United States [to observe] a day of public thanksgiving and prayer” for, among other things,

the peaceable and rational manner, in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national One now lately instituted—for the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed; and the means we have of acquiring and diffusing useful knowledge; and in general for all the great and various favors which he hath been pleased to confer upon us.

“Civil and religious liberty” was not merely new language — it was revolutionary. For the first time in history, a duly elected government was committing itself to protecting, or at least trying to protect, the free exercise of all religions.

What made those words possible was Congress’s adoption, on September 25, of amendments collectively known as the Bill of Rights. The first of those amendments proposed expressly that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

But Washington’s Proclamation also expressed hope that God would “render our national government a blessing to all the people, by constantly being a Government of wise, just, and constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed…” All the people, including women and slaves, of course. Not surprisingly, unlike others in that first Congress, Elias Boudinot had been an early abolitionist and an advocate of women’s rights.

That would take time. Thus, on October 3, 1863, in the middle of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation designating the last Thursday in November as a day of Thanksgiving. In it, he invited his countrymen to be compassionate. He expressed the hope

that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union.

That appeal is eerily relevant today, as dinner conversations can turn into ugly exchanges, family breakups, and worse. Polarization and extremism are increasingly corrupting both major political parties. Ideological labels, often laced with expletives and fueled by a fact-challenged information ecosystem, sow discord and drain our national character. Growing self-doubt about what America truly means and what it stands for undermines the survival of this unique experiment in republican self-government — especially when we have so much to be thankful for!

I recall my family’s first Thanksgiving in America six decades ago. Our little band had arrived from Communist Romania with little more than our clothes, none of us except my multilingual father speaking English. We were stunned by the abundance around us, especially in the supermarkets. The wonderful movie Moscow on the Hudson captures that culture shock perfectly. The notion that we were free to speak our minds, to take any job, attend any school, seemed unbelievable. It had taken my parents seventeen years to be allowed to leave the Workers’ Paradise. At last, here, we became instant patriots.

A holiday like Thanksgiving is inconceivable in a communist country. Since religion is forbidden, forget thanking God for anything — unless you do it in secret, as did my parents, celebrating the Passover seder without telling us what it was. The proletariat, which is supposed to be the ruling “class” (remember, there are no more classes), cannot logically thank itself. (Besides, since the Party members had special stores, special hospitals, and lived in confiscated mansions, it would be not a little ludicrous.) As for the “rights” to speech, the press, and assembly, the Soviet Constitution of 1936 provided the infamous caveat: rights existed only insofar as they were “in conformity with the interests of the working people, and in order to strengthen the socialist system…” Read: forget about it.

Forget about any trimmings. Also, the turkey. Etc., etc. You know the saying: if communism were established in the Sahara, it would run out of sand.

If only it were possible to revive the eighteenth-century tradition of reading Thanksgiving Proclamations aloud, just as many families still read the Declaration of Independence to this day. This passage from Washington’s 1789 Proclamation is worth remembering at a time of unprecedented geopolitical instability: the nation is entreated to pray to “the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be…

to enable us all, whether in public or private stations, to perform our several and relative duties properly and punctually—to render our national government a blessing to all the people, by constantly being a Government of wise, just, and constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed—to protect and guide all Sovereigns and Nations (especially such as have shewn kindness unto us) and to bless them with good government, peace, and concord…

But just in case any do not “shew kindness unto us,” we need to be prepared. Happy Thanksgiving, everybody. L’Chaim!

Juliana Geran Pilon is Senior Fellow at the Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization. Her latest book is An Idea Betrayed: Jews, Liberalism, and the American Left.

Pursuit of Happiness

The Rise of Latino America

In The Rise of Latino America, Hernandez & Kotkin argue that Latinos, who are projected to become America’s largest ethnic group, are a dynamic force shaping the nation’s demographic, economic, and cultural future. Far from being a marginalized group defined by oppression, Latinos are integral to America’s story. They drive economic growth, cultural evolution, and workforce vitality. Challenges, however, including poverty, educational disparities, and restrictive policies, threaten their upward mobility. Policymakers who wish to harness Latino potential to ensure national prosperity and resilience should adopt policies that prioritize affordability, safety, and economic opportunity over ideological constraints.

Exodus: Affordability Crisis Sends Americans Packing From Big Cities

The first in a two-part series about the Great Dispersion of Americans across the country.

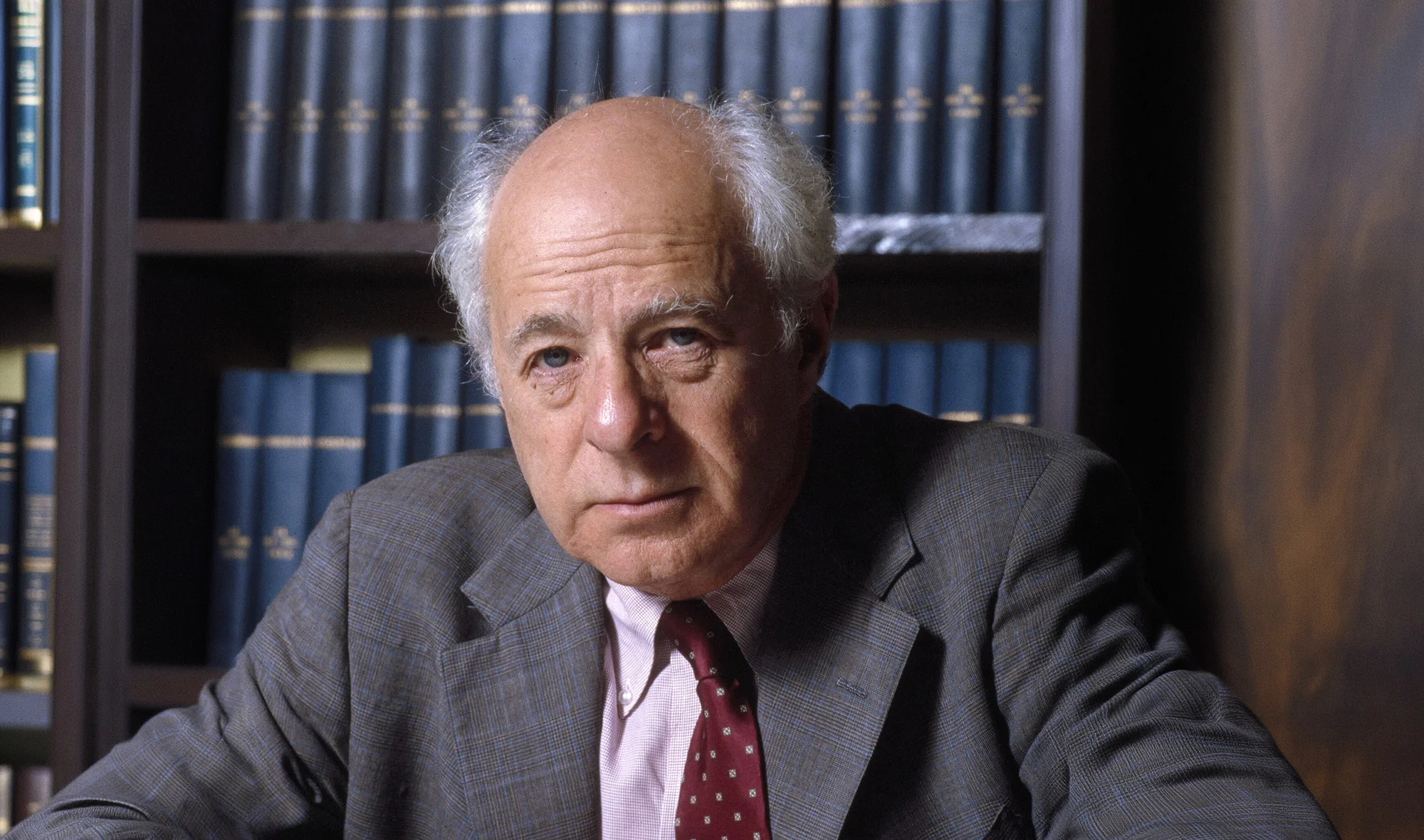

Norman Podhoretz: American Patriot, Faithful Jew, and Indomitable Defender of Civilization

Podhoretz never turned on the promise of America.

America’s Roundabout Revolution

Increased implementation of the roundabout would prove beneficial to the United States.