What Is History's Role in Civic Education?

So long as it does not accept historicism, and holds that the past does honestly speak to the present, a classical, civic education can teach students moral lessons from history in a way that modern professional history cannot.

It is now widely recognized that a renaissance is underway in American civics. Several flagship state universities — Arizona State University, the University of Florida, the University of Texas, and others — have created new schools of civic education, while other elite private schools, such as Yale and Stanford, are following suit.

Precisely what constitutes civic education, however, is still being defined. Broadly, civic education concerns the teaching of subjects that help form well-rounded citizens. This endeavor is necessarily interdisciplinary and encompasses fields such as philosophy, economics, law, literature, and, in particular, political science and history.

The case for political science in civic education is somewhat self-evident. Political science, according to Aristotle, is the science concerned with human flourishing and the characteristics of the Good Life. Proper civic education would therefore need to begin with defining these questions.

By comparison, history’s place in and importance to a civic education is less obvious. While political science deals in generalities — it speaks to precepts applicable to people of all times and places — history seems to do just the opposite — it speaks only to particular cases, peoples, and times. Because political science can speak in such universal terms, it may appear, then, that history ought to take a secondary point of interest in civic thought.

To draw this conclusion, however, would be a mistake. Traditionally, history has played the preeminent role in civic education. It is only due to several regrettable trends within the professional discipline of history that it has lost its former status.

To examine the role of history in civic education, we must first identify the changes within the discipline of history that led to its demotion as a moral and civic teacher.

The first great teachers of civics were the ancient Romans. History, they believed, was the single greatest way to prepare citizens for lives of public service — greater even than the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle.

The Romans taught civics in what they called an “exemplar” mode. Students studied the successes and failures of great men to discern in their own lives what to do and what not to do. This, the Romans believed, would allow citizens, and especially future civic leaders, to learn right and wrong behavior from their ancestors. The great historian Polybius articulated this concept best: the “soundest education and training for a life of active politics,” he said, “is the study of history.” Indeed, the “only method of learning how to bear the vicissitudes of fortune is to recall the calamities of others.”

This pedagogy extended into the Renaissance. The remarkable political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli, for instance, said that “As to the exercise of the mind, a prince should read histories and consider in them the actions of excellent men, should see how they conducted themselves in wars, and should examine the causes of their victories and losses, so as to be able to avoid the latter and imitate the former.”

In this schematic, civic education was primarily a historical education. History was a kind of laboratory in which one could bring precepts from philosophy from the heavens down to earth and test them. So effective was history at offering civic lessons that many thinkers regarded it as a greater teacher than philosophy. According to the Roman historian Quintilian, in fact, historical were a “far greater thing” than philosophic precepts. Similarly, in the seventeenth century, Francis Bacon said that history was a superior instructor of morals; though Plato and Aristotle were great teachers, historians such as Tacitus offered “observations on morals that are much truer to life.”

This approach to civic education persisted until approximately the nineteenth century, when a new philosophical school, called historicism, began to take hold.

Historicism holds that all phenomena are conditioned by their circumstances and, therefore, that history cannot be used to answer questions of right and wrong. Instead, history can only be a facts-based enterprise.

Historicism has significantly impacted both the profession of history and the way history has been taught. Virtually all historians have accepted a fundamental historicist premise: that the past is in some mysterious way unintelligible to us.

According to Quentin Skinner, in fact, one of the most important historians of the past fifty years, the past is necessarily distinct from the present. In principle, there is nothing history can teach us about ourselves, since the world we live in is altogether foreign to every other historical period. History is not about discovering answers to moral or political questions but about understanding how contingent and fragile our world is.

The significant implication of Skinner’s teaching is that “we must do our own thinking for ourselves.” In other words, it is up to us in the present to solve our own problems, because we are ultimately alone in time.

As a result, many popular and academic historians have begun to study the past purely from the perspective of the present. Take, for example, the New York Times’s ultra-controversial 1619 Project, which in 2019 sought to reframe American history around a singular issue: racism. In the words of its creator, Nikole Hannah-Jones, the purpose of the 1619 Project was to reinterpret America’s founding principles in a way that allows us to “change how we understand the unique problems of the nation today.”

Consider also the observation made by James Sweet, the former president of the American Historical Association: the research interests of professional historians are increasingly present-minded. They are turning away from pre-modern history (the period before 1800) and towards modern history (the period from 1800 to the present). Moreover, the study of all historical periods is increasingly conducted through the analytical lenses of so-called “critical” studies, such as critical race theory, critical gender theory, and the like.

In other words, most contemporary popular and professional historians take seriously Skinner’s contention that the past cannot speak to us. They study the past solely from the perspective of the present and transform the facts of history into a narrative that suits us today. This is how, for example, the 1619 Project sees it as acceptable to rewrite America’s founding along racial lines. If the past cannot, in principle, speak to us, then they will make it speak to us in whatever way they see fit.

Unfortunately, there is little to suggest that the modern discipline of history will reform, let alone reject the historicism of the last two hundred years. Though this might spell trouble for professional historians (history majors have precipitously declined in the previous twenty-five years), the renaissance of civic education offers a unique and vital opportunity for history to be taught as it once was.

So long as it does not accept historicism, and holds that the past does honestly speak to the present, a classical, civic education can teach students moral lessons from history in a way that modern professional history cannot.

What this will require, however, is for history to take a prominent place within the civic education movement — at least an equal place alongside political science. Doing so will allow those committed to teaching citizenship to do so with the perennial pedagogical way to instruct students in the proper way to live.

Benjamin P. Haines is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Political Science at Emory University. He holds a Ph.D. in history from Louisiana State University.

Pursuit of Happiness

The Rise of Latino America

In The Rise of Latino America, Hernandez & Kotkin argue that Latinos, who are projected to become America’s largest ethnic group, are a dynamic force shaping the nation’s demographic, economic, and cultural future. Far from being a marginalized group defined by oppression, Latinos are integral to America’s story. They drive economic growth, cultural evolution, and workforce vitality. Challenges, however, including poverty, educational disparities, and restrictive policies, threaten their upward mobility. Policymakers who wish to harness Latino potential to ensure national prosperity and resilience should adopt policies that prioritize affordability, safety, and economic opportunity over ideological constraints.

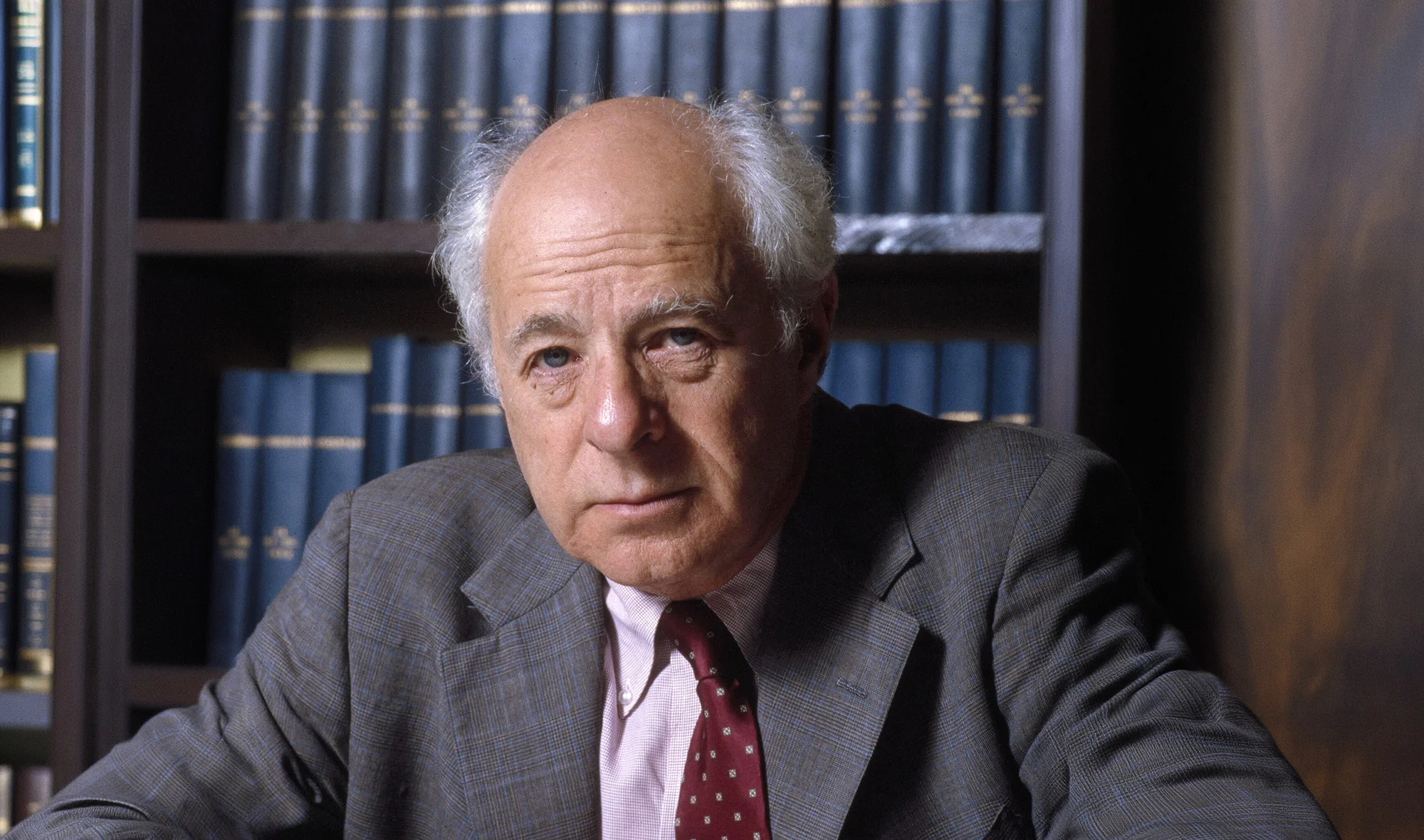

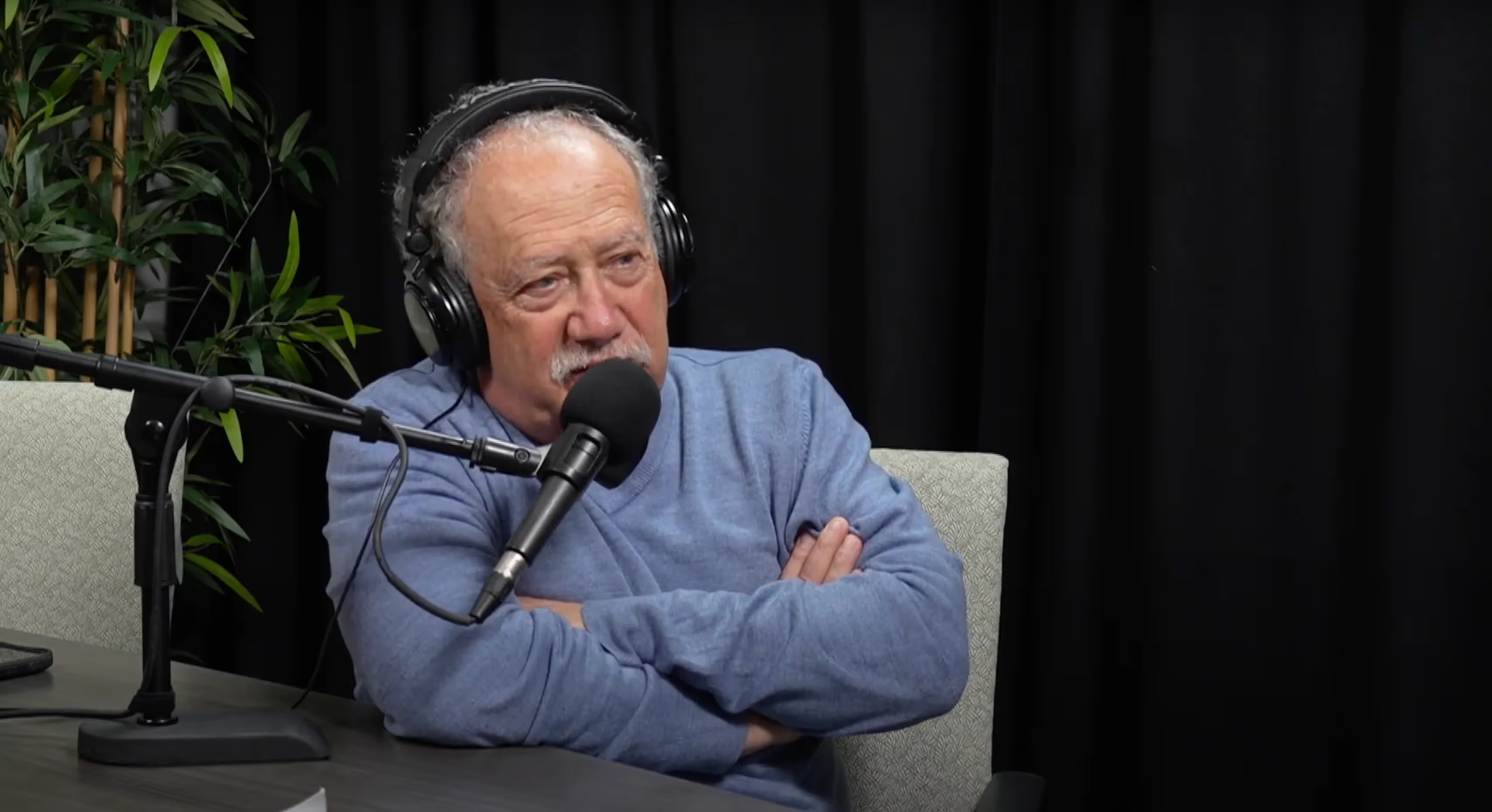

Richard Epstein on Roman Law and Sociobiology

How and why Roman law worked, how it eventually fell apart, and sociobiology as a way to explain the foundations and limits of legal norms.

Becoming All-American

Blue Moon takes place on the evening of March 31, 1943, the opening night of Oklahoma!

The Original Sin of U.S. Health Care

As long as most Americans receive health insurance as an invisible, employer-managed fringe benefit, health care will remain expensive, opaque, and unresponsive.

.jpg)