The War on Affordable and Abundant Energy Continues

Although the latest round of climate warfare may be coming to an end, long-term U.S. energy dominance remains a policy choice.

Editor's Note: Part of Civitas Outlook's Energy Policy Symposium

Climate lawfare has been on a losing streak. Last year, state judges in Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina dismissed cases designed to hold fossil fuel companies liable for global energy consumption under state law. The string of defeats reflects, in the estimation of one of the presiding judges, “a growing chorus of state and federal courts across the United States singing from the same hymnal, in concluding that the claims raised” by climate plaintiffs are beyond the scope of state law.

With climate litigation faltering, the decarbonization effort is shifting to state legislatures. Seeking to capitalize on soaring electricity and home insurance costs, climate activists are repackaging their agenda in an affordability wrapper. The election victories of Mikie Sherrill and Abigail Spanberger — both made lower electricity costs a focal point of their campaigns — in the closely watched gubernatorial races in New Jersey and Virginia last November have given Democrats optimism that energy can be a winning midterm issue this fall. Tim Storey, CEO of the National Conference of State Legislatures, reports that state lawmakers are saying that energy will be their “No. 1 issue” in 2026.

The climate proposals making waves at the state level, however, are more likely to rally left-wing voters than to deliver relief to energy consumers. Rather than increasing energy supply by reducing mandates and reforming tort liability, climate activists are pushing states to adopt “climate Superfund laws” that retroactively charge companies billions for emissions dating back decades and authorize state Attorneys General (AGs) to sue fossil fuel companies over extreme weather events.

Not Your Grandfather's Superfund

Modeled after the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), the 1980 federal law that forced polluters to contribute to a trust fund for cleaning up contaminated sites, climate superfund laws mandate that fossil fuel companies finance state-managed climate adaptation projects. In 2024, New York and Vermont became the first states to establish climate superfunds. The New York law requires fossil fuel companies to fork over $75 billion over 25 years for greenhouse gas emissions dating back decades.

According to the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators, 10 states introduced climate superfund proposals in 2025. Although none of these bills passed, lawmakers in numerous states have either already introduced superfund legislation or are expected to do so later this year. New Jersey lawmakers, for example, tried to create a $50 billion superfund during a lame duck session earlier this month. The bill stalled in committee after organized labor pushed for a pause until the state’s newly elected governor takes office. Proponents are saying they’re “optimistic” that they have the votes to pass the bill later this year.

Climate superfund laws have myriad legal and policy problems. While they share the same name as the federal superfund law, the resemblance ends there. The federal Superfund process involves a local operation that typically requires the owner of the toxic site or the party responsible for the contamination to finance the cleanup. The law provides procedures that avoid finger-pointing, but such instances are rare. The parties responsible for the pollution have borne most of the federal Superfund cleanup costs.

Retroactive Carbon Tax

By contrast, the state climate superfunds are, in effect, a retroactive carbon tax. They impose a multibillion dollar levy on energy producers for supplying products widely used by people for a broad range of socially beneficial uses, from transportation and home heating to cooking, agriculture, medical equipment, and clothing. Even the governments imposing the de facto carbon tax have used the fossil fuels they’re now targeting to heat state buildings and fuel state vehicle fleets for decades.

There’s also the problem of tracing climate change to a particular emission source. To quote Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, “emissions in New Jersey may contribute no more to flooding in New York than emissions in China.” The New York and Vermont laws address the traceability problem by holding energy producers responsible for climate change under a strict liability standard that requires no proof linking a particular company’s emissions to any climate disaster. Business groups are challenging the arbitrariness of the tax as a violation of due process.

Apart from the traceability problem, what’s the right rate for a carbon tax? As Travis Fisher from Cato points out, accurately assessing the tax requires calculating the cost of climate change on society, otherwise known as the social cost of carbon (SCC). But federal estimates of the SCC over the past decade, Fisher writes, “ranged from near zero to $190 per ton.” Given this lack of consensus, the climate superfunds don’t come close to making responsible parties pay society back for the actual damage they caused. They’re a pure moneygrab.

Even if a state could calculate the SCC and trace the cost back to a particular emissions source, there’s still a fundamental problem with state like New York hitting not just U.S. oil and gas majors, but also foreign energy producers like Saudi Aramco ($640 million annually), Mexico’s Pemex ($193 million annually), Russia’s Lukool ($100 million annually), with massive fines based on their overall emissions. The regulation of interstate and international greenhouse gas emissions, in the words of the Second Circuit, “is simply beyond the limits of state law.” The Trump Justice Department has sued to block the New York and Vermont superfund laws on these grounds.

As though all these legal problems weren’t enough, climate superfund proponents have one more unconstitutional trick up their sleeves. New York’s law requires that at least 35 percent of the superfund’s outlays must “directly benefit disadvantaged communities.” The law further designates a “climate justice working group” with the responsibility of identifying who belongs within this category based on whether an area has a high concentration of people who “have historically experienced discrimination on the basis of race or ethnicity.” But states can’t evade the Fourteenth Amendment by proxy discrimination. “What cannot be done directly,” as the Supreme Court has long recognized, “cannot be done indirectly.”

Insurance Gambit

New York, California, and Hawaii are also considering new laws authorizing their AGs to sue fossil fuel companies over insurance premium increases linked to climate change. Previously, California and Hawaii proposed legislation encouraging insurers to bring climate liability cases against energy companies, but the insurers opposed the measures because of their skepticism over whether they could prove that a particular company’s emissions were a material cause of an extreme weather event. According to the Hawaii Insurers Council, there is “no real consensus” when it comes to tracing the cause of climate disasters. Seren Taylor, whose organization represents large California insurers, explained to Politico that “it would not be good for policyholders if insurers had to spend tens of millions of dollars on lengthy, losing lawsuits.”

The reluctance of insurers is well-founded. Take, for example, the case brought by the estate of Julia Leon, who died of heatstroke in her car when temperatures around Seattle reached 108 degrees in June 2021. Last summer, the private law firm behind a landmark Montana court ruling that climate change injured the youth filed a first-of-its-kind case seeking to hold energy companies liable on the theory that their emissions caused the extreme heat wave that resulted in Ms. Leon’s death.

For the same reasons raised by the insurers in Hawaii and California, the Leon case faces an uphill battle: specific extreme weather events are not easily attributable to emissions. The 2023 Oregon Climate Assessment found “no evidence” that the Pacific Northwest “heat dome” four years ago was “made more likely by climate change.” Likewise, University of Washington researchers determined that at most 1 degree Celsius of the excessive heat could be attributed to human activity. The attribution problem, moreover, is not restricted to this particular extreme weather event. Last summer’s widely covered Energy Department report on greenhouse gas emissions disputed the notion that there have been long-term increases in hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, droughts, wildfires, or other extreme weather events.

Notwithstanding the skepticism of respected scientists and insurance specialists, state activists are eager to spend taxpayer money to empower like-minded state AGs to lead lengthy litigation efforts with a low probability of success. These cases will be expensive for energy producers to defend. The defense costs and legal uncertainty will only impede efforts to increase energy supply and lower consumer costs. Like the earlier iterations of climate lawfare, the process is the punishment.

Tellingly, the states pushing these aggressive measures are most often the largest offenders on affordability. New York’s electricity prices were over 60 percent higher than Florida’s last year, while California’s rates were double the national average. Out-of-state energy companies make useful scapegoats for such a record. But the durability of the effort reveals a more fundamental lesson: Although the latest round of climate warfare may be coming to an end, long-term U.S. energy dominance remains a policy choice.

Michael Toth is Research Director of the Civitas Institute at the University of Texas at Austin.

Politics

National Civitas Institute Poll: Americans are Anxious and Frustrated, Creating a Challenging Environment for Leaders

The poll reveals a deeply pessimistic American electorate, with a majority convinced the nation is on the wrong track.

.webp)

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

This article explores Leo Strauss’s thoughts on Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1954 “Natural Right” course transcript.

%20(1).avif)

Long Distance Migration as a Two-Step Sorting Process: The Resettlement of Californians in Texas

Here we press the question of whether the well-documented stream of migrants relocating from California to Texas has been sufficient to alter the political complexion of the destination state.

%20(3).avif)

Who's That Knocking? A Study of the Strategic Choices Facing Large-Scale Grassroots Canvassing Efforts

Although there is a consensus that personalized forms of campaign outreach are more likely to be effective at either mobilizing or even persuading voters, there remains uncertainty about how campaigns should implement get-out-the-vote (GOTV) programs, especially at a truly expansive scale.

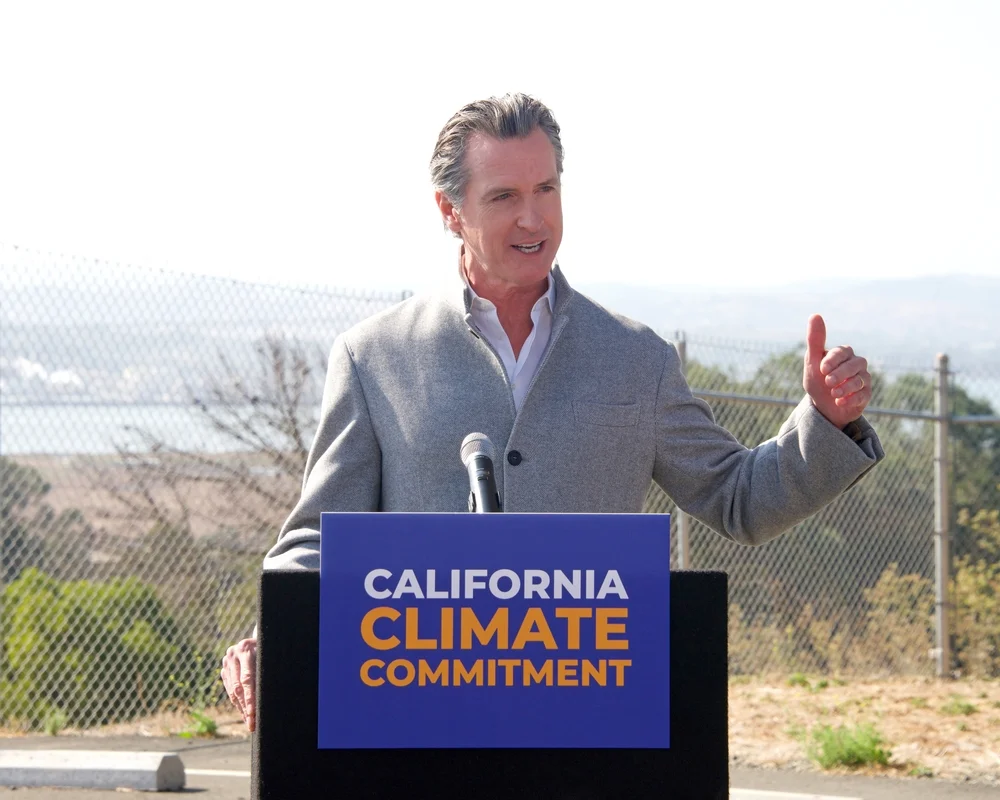

California’s Green Policies Destroy Blue-Collar Jobs

The problem here lies not with racism, or lack of reparations, as Newsom and “progressives” insist, but with their own policies, which devastate minority communities.

There's a Perception Gap With the U.S. Economy

As we approach another election cycle, it’s worth asking: what’s real, what’s political theater, and what does it all mean if Democrats regain control of the House?

The Not-So Reckless Attack on Iran

The Iranian government does not have either the leadership or the resources to mount any sustained military response to the forces arrayed against it.

The Healthcare Symposium

We’ve asked James Capretta, Sally Pipes, and Avik Roy to opine on the future of healthcare policy in America.

.avif)

.jpg)