The AI Frontier Must be Fiercely Competitive

We must actively foster the conditions for competition to ensure the future of AI is not dictated by the few but discovered by the many.

The mass-produced car was a watershed moment for Americans. But under the control of three firms — with Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler cornering consumer sales — choices were limited, innovation followed similar paths, and models looked alike.

Having a few companies exercising control of new technologies comes at a cost. Competition increases market pressure to spur the kind of innovation that leads to safer, more affordable products. What’s more, a smaller market is more susceptible to regulatory capture, where government officials and corporate leaders indirectly collude to preserve their interests. These concerns regarding concentration are particularly worrisome in the context of AI.

There are two types of threats arising from excessive concentration in the frontier AI space: those stemming from limited competition and those stemming from regulatory control.

Limited Competition

A market that lacks dynamism exerts insufficient pressure on companies to align their products with consumer preferences and society’s broader interests. Market power enables them to charge higher prices for inferior products. What’s more, governments seeking to regulate concentrated industries must walk a fine line to avoid pushing them out of business or, minimally, reducing the availability of the good or service, inferior as it may be.

Consider the telegraph. After Congress deferred its opportunity to play a more substantial role in facilitating a competitive market, Western Union managed to gobble up its nascent competitors. The telegraph giant justified its ever-greater market share by appealing to the need for a seamless national communications infrastructure — as if there were no other means to achieve that besides monopoly control.

Yet, it soon became clear that the lack of competition allowed the company to focus more on profit than on properly maintaining and improving its network. As Gardiner Hubbard pointed out in 1883, “[T]he Western Union system is unrivaled; but as a telegraph for the people it is a signal failure.” He observed that a more competitive European ecosystem was more consumer-friendly, resulting in a freer flow of ideas and goods. Consider that the rate in England to send twenty words was twenty-five cents, whereas the rate to send just ten words was thirty-eight cents in the US.

From time to time, Federal and state regulators stepped in to try to encourage more pro-competitive behavior. They largely failed. In fact, some of their interventions actively entrenched Western Union’s dominance. It ultimately took the introduction of an entire new communications technology to provide the American public with a meaningful alternative. Of course, that was only after decades of Western Union dominance — decades during which millions of Americans lacked the financial means to send messages over an expensive and unreliable telegraph infrastructure.

The Western Union saga provides a clear lesson for the frontier AI space: a market dominated by a handful of entities, and shielded from competitive pressure, will inevitably under-serve the public. Critical technology can become stagnant and extractive when one or a few companies set the terms.

Regulatory Control

A heavy regulatory hand may unintentionally lock in less safe and less capable model architectures, training procedures, and evaluation tactics. W. Kip Viscusi detailed this product liability paradox, in which regulation can make us less safe. When courts or regulators treat new risks as distinct and more worthy of scrutiny than well-known risks, then novel products that are, or may soon be, safer than existing products can be delayed or denied due to a bias toward the status quo.

This ambiguity creates a chilling effect on innovation. AI developers, cautious of inviting legal scrutiny under vague liability standards or regulations, will naturally hesitate to explore novel strategies. They may adhere to established architectures and training methods, even if newer, untested approaches could yield significant gains in safety and alignment. Regulators, on the other hand, often justify such broad interventions as necessary. They may argue that, without a strong guiding hand, the market lacks sufficient incentive to prioritize the general welfare over profit. This creates a regulatory paradox: the attempt to de-risk the market unintentionally freezes it, locking in incumbent technologies and potentially inferior models.

A litany of scholars have identified this sort of concentration in the drug development space. Despite incredible demand for efficacious and affordable drugs, a slew of regulations have foreclosed any significant competition. Things from clinical trial requirements to prolonged analysis by the Food and Drug Administration have made “upstart drug developers” an oxymoron. The barriers to market entry, as well as the tremendous uncertainty surrounding drug review, effectively create a moat around incumbents who are just fine with nursing the profits from tried-and-true remedies.

Large pharmaceutical companies, in a manner similar to Western Union, tend not to face the competitive pressures that might push them to the frontiers of their field to offer consumers safer drugs sooner. Lower regulatory hurdles could at least partially remedy this status quo by allowing more firms to introduce more products more quickly. Of course, this may increase the incidence of unintended consequences among patients. Yet this cost must be evaluated without treating “new risks” as more significant than established risks. A failure to design such a system effectively allows the relevant regulatory body to favor the known, ongoing harms of the status quo — the lives not saved — over the potential harms of innovation.

Restoring The Frontier of Competition

These parallel histories of the telegraph and pharmaceutical industries tell a single, cautionary tale for the age of AI. They tell us that whether a moat around incumbents is built by market consolidation or by regulatory design, the outcome is the same: a stagnant, uncompetitive ecosystem that stifles innovation and poorly serves the public.

What conditions are necessary for a competitive frontier AI market to enable effective, aligned AI?

First, consumer knowledge. Consumers need to understand the likelihood and severity of the risks and benefits associated with selecting a particular product. This condition is arguably improving as individuals and organizations concerned about AI risks continue to conduct and share their research on model behavior. New regulations, such as SB 53 in California, that mandate labs disclose certain safety-related information, are intended to further inform consumers. Labs are also making more information about their models more accessible. It appears to be working. Many, if not most, Americans seem to be attentive to the risks posed by AI tools and may therefore demand products and models with lower risk. By extension, we could expect insurers, corporate board members, and CEOs to actively assess the risks an AI model poses before entering into an agreement with a lab, especially given the costs of involvement in an AI incident.

Perhaps the largest informational gap among consumers (and regulators) is undercoverage of the risks of not using AI tools. Despite Waymo's claim that its autonomous vehicles (AVs) have substantially better safety metrics than human drivers, many people (including policymakers) have proposed outright bans on this life-saving technology. Despite Emory University and the Georgia Institute of Technology developing a biopatch that can accurately predict when outdoor workers may experience overheating, widespread adoption of AI wearables will likely be hindered by outdated privacy laws. Absent reliable information about these products and the opportunity cost of delaying their deployment, consumers will not be able to demand them.

Still, as evidenced above, it is likely that the average consumer, especially those in a position to use frontier AI models, such as major corporations, may prefer a demonstrably safer model to alternatives, all else equal. This suggests that if Lab A and Lab B deployed models with similar capabilities, potential users would evaluate model safety, including alignment with user preferences, as part of their purchasing decisions. Corporate leaders may be slower to adopt Grok than certain versions of ChatGPT, for example, because of concerns about Grok’s risk profile despite the two models having comparable capabilities.

Second, we need a diverse range of models with varying capabilities, safety levels, and prices. In such a market environment, consumers could fully act on their preferences by selecting a product that offers the desired mix of safety, affordability, and capability. If consumers prioritize safer models, then firms will be incentivized to produce them.

This diversity condition is far from satisfied, at least from the perspective of the consumer AI-as-a-service sector. OpenAI accounts for approximately 60 percent of that market. Antitrust experts worry that the firm’s dominance will only grow in the coming years. Asad Ramzanali, Director of AI and Technology Policy at the Vanderbilt Policy Accelerator, contends that OpenAI and a select few other companies are “building an AI economy where the same companies own the infrastructure, the technology, its applications — and where no one else gets a fair shot.” If Ramzanali is right, then AI’s future will be dictated by OpenAI and whatever firms manage to stick around. Such a market may not provide other firms with an opportunity to compete.

Several signals suggest that increased competition may be imminent. New entrants have emerged across the tech stack, chipping away at the market share of existing giants. Poolside has made a splash in the data center market. Flower AI and Vana are collaborating on novel models that may supplant existing generative AI models in certain contexts. Protege collects and sells data that nascent AI startups can use to drastically improve their models. Yet, these signals are faint and flickering. So long as the name of the AI game is scale — more data, more compute, more energy, more (and more expensive) talent, then the nature of the industry itself will tend toward concentration.

Yet, scale need not be synonymous with concentration. A few regulatory measures designed to encourage competition can increase the likelihood that more stakeholders have the resources required to enter the market. For example, governments could:

Open access to large, high-quality datasets. The AI Action Plan, for example, took two key steps in this regard. First, it called on the National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, and others to increase access to federal datasets. Second, it directed the OMB to facilitate improved data collection across the federal government with an eye toward augmenting the number and quality of datasets available. While the resulting datasets may not rival the data held by OpenAI, Meta, and other AI leaders, this and related efforts are nevertheless a pro-competition move and lower barriers to entry.

Support Sematech-like initiatives to support pre-competitive research. This would focus on fundamental, non-commercial challenges that currently act as barriers to entry, such as developing reliable and efficient training strategies and robust alignment techniques.

Build public AI infrastructure. While data and foundational research are vital, they remain insufficient so long as the tools needed to use them—the data centers themselves—remain consolidated. Initiatives like the CalCompute project and Empire AI offer a compelling blueprint: establish a public cloud or a shared compute cluster, offering affordable access for researchers and startups

Will More Competition Guarantee Safety?

The market-based approach called for here is not perfect; it’s a prime example of the fact that when dealing with wicked problems, “there are no solutions, just tradeoffs,” to paraphrase Thomas Sowell. Many labs pushing the frontier of the technology may make worst-case scenarios, such as loss of control or the stealing of model weights by bad actors, more likely. These concerns likely explain why the Biden administration allegedly considered keeping the number of frontier firms relatively low.

But the nature of the tradeoff is key. The risk of concentration, as the histories of the telegraph and pharmaceutical industries show, is not a ‘risk” so much as a guarantee of stagnation, regulatory capture, and inferior outcomes for the public. It exchanges the potential harm of a novel technology for the certain harm of a stagnant one. Opting for a more competitive market, therefore, best framed as the act of choosing which risk profile we prefer: a centralized, rigid system, or a decentralized, dynamic one that at least has a mechanism to adapt, innovate, and self-correct.

The challenge of frontier AI is not simply to manage its development, but to avoid the dangers of concentration that have stifled critical technologies in the past. Whether built by a dominant firm or by a heavy-handed regulator, a moat around incumbents is likely to yield AI that is less capable, less aligned, and less responsive to the public good.

The path forward is not to anoint a few “responsible” stewards or to freeze the field with precautionary regulation. We must actively foster the conditions for competition — through public data, shared foundational research, and accessible compute. This strategy is the only one that trusts a decentralized market of consumers and producers, rather than a centralized authority, to navigate the profound and inevitable tradeoffs between innovation and safety.

It is the only way to ensure the future of AI is not dictated by the few but discovered by the many.

Kevin Frazier directs the AI Innovation and Law Program at the University of Texas School of Law. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Abundance Institute and an Adjunct Research Fellow at the Cato Institute.

Pursuit of Happiness

The Rise of Latino America

In The Rise of Latino America, Hernandez & Kotkin argue that Latinos, who are projected to become America’s largest ethnic group, are a dynamic force shaping the nation’s demographic, economic, and cultural future. Far from being a marginalized group defined by oppression, Latinos are integral to America’s story. They drive economic growth, cultural evolution, and workforce vitality. Challenges, however, including poverty, educational disparities, and restrictive policies, threaten their upward mobility. Policymakers who wish to harness Latino potential to ensure national prosperity and resilience should adopt policies that prioritize affordability, safety, and economic opportunity over ideological constraints.

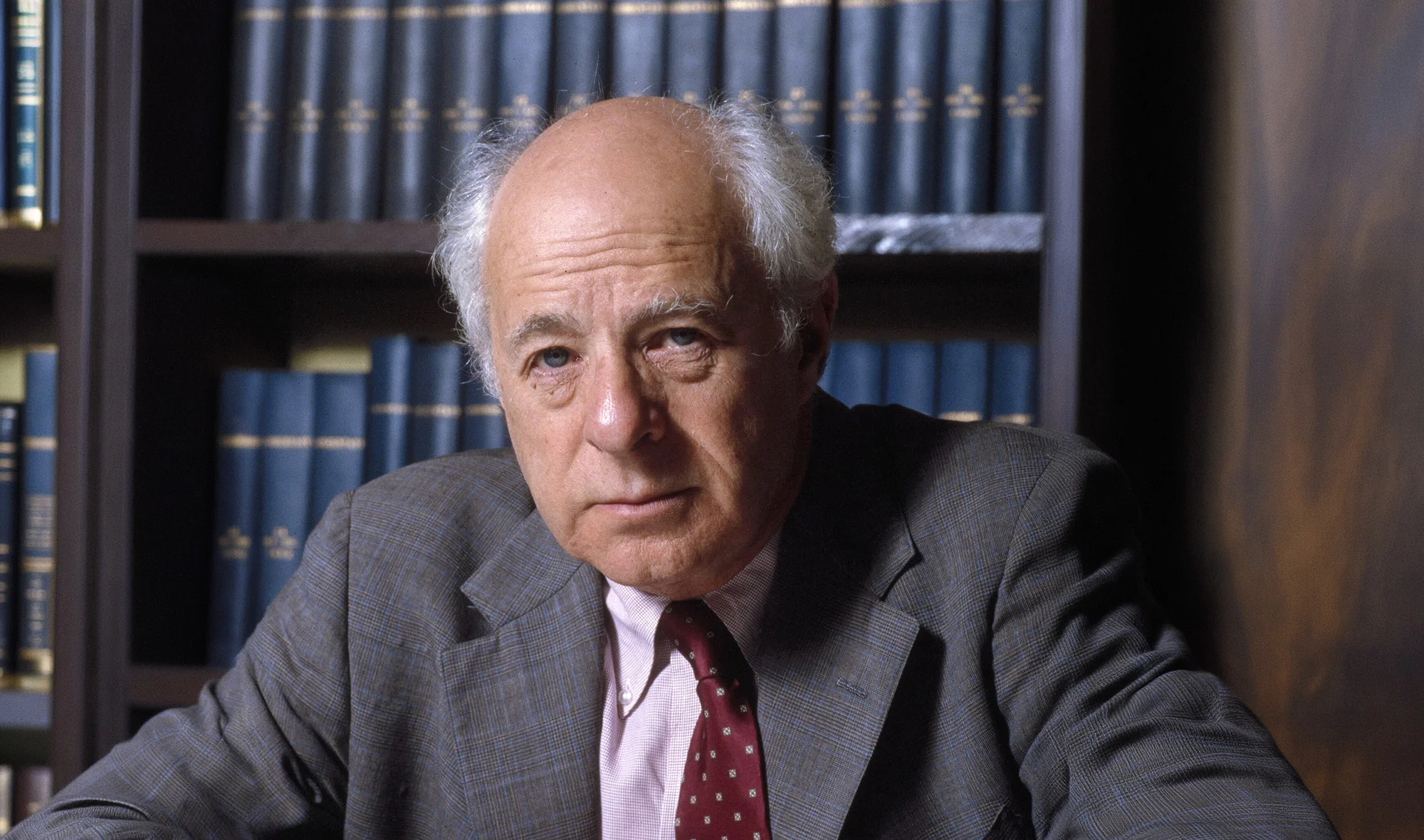

Richard Epstein on Roman Law and Sociobiology

How and why Roman law worked, how it eventually fell apart, and sociobiology as a way to explain the foundations and limits of legal norms.

Becoming All-American

Blue Moon takes place on the evening of March 31, 1943, the opening night of Oklahoma!

The Original Sin of U.S. Health Care

As long as most Americans receive health insurance as an invisible, employer-managed fringe benefit, health care will remain expensive, opaque, and unresponsive.

.jpg)