From Max Weber to Charlie Kirk: On Political Action in Extreme Times

Kirk's emphasis on his Christian faith as much as his politics represents the limits on what politics can accomplish.

“The decisive means for politics is violence," Max Weber declares at the climax of his dense, difficult but profound January 1919 lecture “Politics as a Vocation," adding that "the world is governed by demons, and that he who lets himself in for politics, that is, for power and force as means, contracts with diabolical powers..."

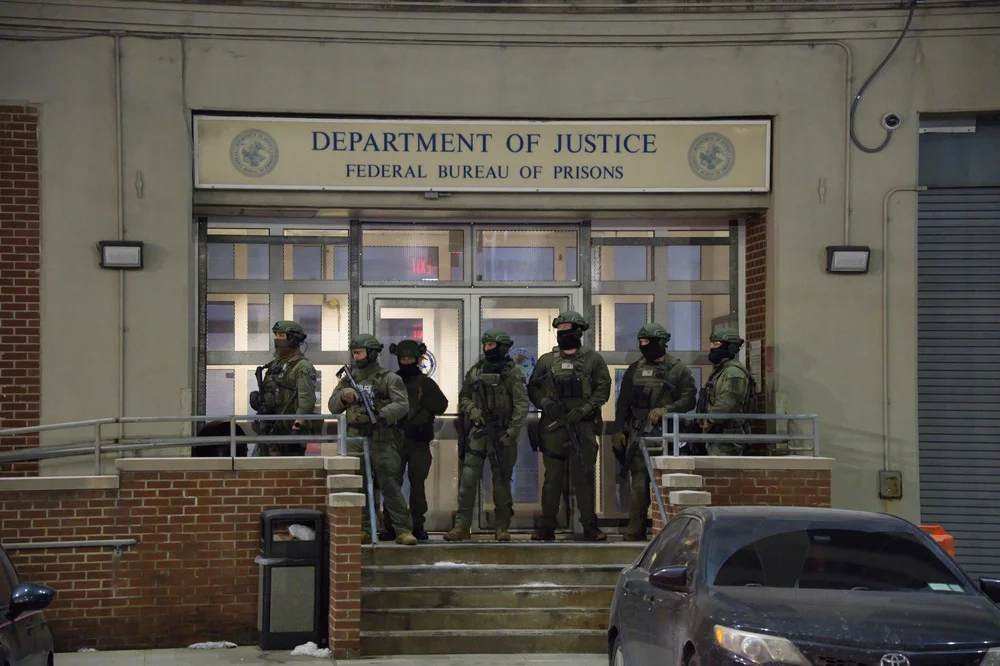

I am always drawn back to Weber's challenging lecture whenever events like the political murder of Charlie Kirk and renewed talk of civil war erupt ominously as they have now. It is not supposed to be this way in a liberal democracy, where we are meant to do battle at the ballot box, year after year. “Where ballots replace bullets" might be the simplest and shortest definition of liberal democracy. Only once has this practice failed to get America to the ballot box again, though Harry Jaffa warned that our Civil War “is the most characteristic phenomenon in American politics, not because it represents a statistical frequency, but because it represents the innermost character of that politics." That "innermost character" of fundamental division is back on full display, but the problem now may go much deeper than mere partisan or ideological dispute.

Weber's statements on violence and political demons are especially jarring from someone who is otherwise regarded as a leading theorist of boring bureaucratic government, in which stability and effective—if uninspiring—governance would proceed from the guidance of positive social science and enhanced rational state capacity. It is and remains a primary modern framework for reducing violence and conflict in politics, as Weber's closest intellectual rival, Woodrow Wilson (yes, Wilson), equally understood and advocated.

Why the seeming radical departure from Weber's core approach to politics, and does it hold relevant lessons for today?

For readers unfamiliar with this famous lecture, it was given in the early weeks after Germany's capitulation in World War I, when the country was plunged into revolutionary crisis, with full blown civil war not only in prospect, but actively underway in local areas like Munich. The struggle for power involved violence, including assassinations in the street, and a series of unstable provisional governments mostly set up by force. Above all, the youth of Germany were in a state of high agitation. One of Weber's most consequential students, Ernst Toller, described the scene thus:

The war had driven [students] from their study tables; they were all questioning the values of yesterday and today. But the young wanted more than theorizing. To them the world into which they were born seemed ripe for annihilation, and they sought a way out of the dreadful confusion of the times. . . It was to Max Weber that most of the youth of the day turned, profoundly attracted by his intellectual honesty. He loathed political romanticism. . . establish a new foundation for liberal democracy in response to the devastating challenges it faced.

In other words, the packed auditorium of students who sat in rapt attention for this nearly three-hour lecture (among them was a young Max Horkheimer, co-founder of the “Frankfurt School" a generation later) wanted to be told what to think about the crisis and what to do. Many of the students came away “frustrated and disappointed," as Horkheimer later wrote. Weber was attempting to transcend the white-hot passions and tempers of the moment, but the depths of his lengthy excursion was lost on most of the audience.

Weber's wide-ranging lecture covered a lot of ground, but two central purposes stand out for their continuing relevance. First, he was attempting to work out a new foundation for liberal democracy against the devastating challenges to it from Marx on the left and Nietzsche on the right. However, he is nowhere explicit about this. In their own way, Marx and Nietzsche attacked the central principle of liberal democracy—the equal natural rights of all humans, and thus the legitimacy of government grounded on the consent of the governed.

Marx's version of systemically oppressive class conflict and Nietzsche's assertion of human inequality both remain powerful influences today. The left's current “oppressor-oppressed" framework traces directly back to Marx, however modified by postmodern categories of “power structures" and other cliches, while Nietzsche's attack on human equality is at the root of contempt for constitutional democracy among many figures of the “alt-right."

Weber never considers returning to or championing the older view of Lockean individual natural right or social contract theory, so powerful did he regard the Marxist-Nietzschean challenge. Legitimate government in modern times could only rest on tradition (or history), the personal charisma of a leader or strongman, or positivist law. All three have their obvious defects, which is why Weber emphasized the importance of political parties (and/or political machines—Weber thinks Tammany Hall is not necessarily to be abjured) and a permanent bureaucratic class to provide for stability.

Weber surely knew that, amidst a revolutionary moment, this framework would be wholly unsatisfying to his student audience, which explains his second main purpose unfolding in the long conclusion of the lecture, which differs starkly from the turgid first two-thirds. His purpose was to speak personally to young people about how to approach their engagement with political life. Here Weber lays out his famous pairing of the “ethic of responsibility" and “ethic of ultimate ends." On the surface these are relatively simple to make out: a person who chooses to act according to the “ethic of responsibility" will consider first and only the likely consequences of his choices and actions, while the “ethic of ultimate ends" describes the revolutionary or chiliastic prophet too often willing to commit any extreme act — especially of violence — to achieve the ultimate and just achievement of utopia.

While Weber was himself committed to the ethic of responsibility, he did not rule out a role for the ethic of ultimate ends (he points to Martin Luther as a salutary example of the ultimate ethic of a mature person), but he abandoned any hope that the two can be reconciled or balanced. “One cannot prescribe to anyone whether he should follow an ethic of ultimate ends or an ethic of responsibility, or when one and when the other." Weber knew that a direct caution against youthful political romanticism would fall on deaf ears, but just as he gave up on natural right as the basis for liberal democracy, he also dismissed classical prudence as the means of political judgment.

Still, he was most alert to the present risk of revolutionary fervor, especially from the far left; Weber abhorred Communism because he thought Communist rule would discredit socialism for a century. More than that, Weber worried that the passionate intensity of revolutionary moments would result in tragedy, both personally and politically. He feared, in the words of Daniel Bell—Weber's most faithful modern successor in many ways— “the unchained holocaust that excesses of passion could fire. . . Weber, in his own anguish as seeing the young men who had stirred his life in his old age turn to revolution, had sought to deter them, or at least to answer them before History."

Bell thought Weber was not speaking in the abstract in the climax of his lecture, but in fact had specific individuals from among his students in mind. One was the aforementioned Ernst Toller, a poet and playwright who whipsawed from pacificism (one form of an ethic of ultimate ends) near the end of the war to commanding a Red Army faction in brutal street fighting during a short-lived “Soviet republic" in Munich (which the Communists opposed because they didn't control it). Toller wrote in his autobiography 15 years later:

I felt at odds with myself. I had always believed that Socialists, despising force, should never employ it for their own ends. And now I myself had used force and appealed to force; I who hated bloodshed had caused blood to be shed.

Weber subsequently advocated for Toller's release from prison after his arrest and sentencing, and ever after, Toller wrestled with the dilemma of the use of violence for just ends, eventually wandering back to his previous pacifism, largely a broken man. Toller committed suicide after the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1939, “his nerves broken," Bell wrote, “by the tension of his pacificism and his certainty of a new, brutal war. . . he acted out his own ethic of ultimate ends."

Bell identified a second figure on Weber's mind in “Politics as a Vocation"—the Hungarian theorist Georg Lukacs. The young Lukacs, who studied at Weber's feet, was fixated on the ethical and theological elements in Dostoevsky and Kierkegaard, keenly aware in his early writings of the abyss that potentially awaits anyone who throws in for the extremism inherent in an ethic of ultimate ends. Weber was therefore shocked when Lukacs threw in fully with the Hungarian Communist Party, becoming a theorist and defender of Leninism, repudiating his early literary work, and embracing the idea that “the highest duty for Communist ethics is to accept the necessity of acting immorally."

At least the agitated youth of a century ago understood extreme acts involved fear and trembling. That residual has been fading for decades. Bell noted forty years ago that political violence, while still shocking, seems increasingly anesthetized. Kirk's killer, who seems only weakly ideological, unlike the Lukacs and Tollers of long ago, dismissed even reasoning about violence with the comment that “I had enough of [Kirk's] hatred. Some hate can't be negotiated out." Meanwhile, the killer of a corporate CEO is enthusiastically celebrated by many on the left.

If Weber's plea for an ethic of responsibility was lost on the youth of his time, perhaps it could be better used by adults today rather than the young. And yet we have countless examples of rhetorical irresponsibility from adults. Egregious examples are legion by this point, but just take Sen. Chris Murphy's (D-CT) statement that “the current situation is described as a war to save the country, requiring a willingness to do whatever is necessary." Doubtless Sen. Murphy did not mean to sanction assassination, nor Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY) with his menacing comments toward the Republican Justices of the Supreme Court (“You have released the whirlwind and you will pay the price; you won't know what hit you if you go forward with these awful decisions"), after which another deranged young person attempted to kill the newest Justice on the Court. Should we be surprised that immature and defectively educated young people can find implied approval from such careless language?

Readers familiar with Weber's lecture will recall the ringing words of his final paragraph that “Politics is a strong and slow boring of hard boards," but before reaching that sober note, he makes a more fundamental caution: “He who seeks the salvation of the soul, of his own and others, should not seek it along the avenue of politics." Maybe the most significant aspect of Kirk's too-brief life and career is how he progressed from being a mere polemicist and campus brawler to an evangelist more deeply rooted in his growing Christian faith rather than politics alone.

Weber attempted to finesse the distinction between the ethic of responsibility and the ethic of ultimate ends; it is clear that a key factor is simple maturity, although that is no guarantee. Some people never grow up, even as they age. Kirk's turn to emphasizing his Christian faith as much as his politics represents a working out of the two ethics. In elevating his own ethic of ultimate ends, he was clearly tilting to the view that individual salvation and redemption would solve more political problems than another ideological manifesto. Early Kirk enthusiasts thought he might have a political career someday, culminating in a run for president. More recently, people closest to him thought it more likely he'd become the next Billy Graham. The final tragedy of Kirk's murder is that we will not see how the evolving equilibrium of this fast-maturing leader between an ethic of responsibility and an ethic of ultimate ends, rightly understood, would play out in the fullness of time.

Steven F. Hayward is the Edward Gaylord distinguished visiting professor at Pepperdine University’s School of Public Policy. He is a contributing editor at Civitas Outlook.

Politics

.webp)

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

This article explores Leo Strauss’s thoughts on Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1954 “Natural Right” course transcript.

%20(1).avif)

Long Distance Migration as a Two-Step Sorting Process: The Resettlement of Californians in Texas

Here we press the question of whether the well-documented stream of migrants relocating from California to Texas has been sufficient to alter the political complexion of the destination state.

%20(3).avif)

Who's That Knocking? A Study of the Strategic Choices Facing Large-Scale Grassroots Canvassing Efforts

Although there is a consensus that personalized forms of campaign outreach are more likely to be effective at either mobilizing or even persuading voters, there remains uncertainty about how campaigns should implement get-out-the-vote (GOTV) programs, especially at a truly expansive scale.

There's a Perception Gap With the U.S. Economy

As we approach another election cycle, it’s worth asking: what’s real, what’s political theater, and what does it all mean if Democrats regain control of the House?

International Law Is Holding Democracies Back

The United States should use this moment to argue for a different approach to the rules of war.

Trump purged America’s Leftist toxins. Now hubris will be his downfall

From ending DEI madness and net zero to securing the border, he’ll leave the US stronger. But his excesses are inciting a Left-wing backlash

California’s wealth tax tests the limits of progressive politics

Until the country finds a way to convince the average American that extreme wealth does not come at their expense, both the oligarchs and the heavily Democratic professional classes risk experiencing serious tax raids unseen for decades.

The Venezuela Symposium

Eight Latin American contributors discuss Venezuela's future and its wider consequences for the region.

Venezuela Post-Maduro

Indeed, for many, the Venezuelan situation seemed to have no other way out, since everything had already been tried without success. It was about time.