The Wages of War and Punishment

War invokes powers too extraordinary to be used against crime.

The controversy over the Trump administration’s attack on alleged Venezuelan drug trafficking boats raises questions like those raised by the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Until that day, administrations of both parties had considered terrorism a matter for law enforcement. But on September 11, the United States decided that it could wage war not just against other nations, but now against a non-state organization. Understanding the decision in which I participated as a Justice Department official will help identify what features of today’s attacks fall on the right side of the line between crime and war.

On the afternoon of September 11, 2001, Washington fell silent. The Justice Department was empty. Only the command center, where national security officials crowded in, and the FBI across the street, remained active. I remember wandering the building that night for dinner and finding nothing open — no cafeterias, no late-night takeout, only vending machines. Driving home across the 14th Street Bridge, I saw the Pentagon still burning, the skyline lit not by office lights but by flames. It was a sight I never thought I would see in my lifetime.

As an official in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, I advised the Attorney General and the White House that the U.S. could wage war against al Qaeda without blurring the distinction between crime and war. This was a critical distinction because war powers are extraordinary. The attacks of 9/11 made clear that terrorism could no longer be treated merely as a matter of law enforcement. It was a) organized violence, b) of a level normally in the hands of nation-states, and c) directed against the American people for political purposes — and thus properly the subject of war.

Once the U.S. decided that it would wage war against an organization — as opposed to a nation — President Bush had the power “not only to retaliate against any person, organization, or state suspected of involvement in terrorist attacks on the United States, but also against foreign states suspected of harboring or supporting such organizations” (in the words of the Authorization for the Use of Military Force enacted on September 18, 2001). This power is not punitive. It included “the power to respond to past attacks and the power to act preemptively against future ones.” With crime, the government acts to punish those who have perpetrated past harms on society. With war, the government acts to prevent future harm to society.

The distinction between war and crime remains crucial today. We are again debating whether the nation can use military force against non-state actors, this time drug cartels rather than terrorist groups such as al Qaeda. The harm caused by illicit narcotics is undeniable. Drug overdose deaths in a single year now surpass total American deaths in many major wars. But the United States cannot confuse crime with war. To do so would dangerously expand the scope of military force into areas of ordinary social problems and erode the rule of law. Armed force is justified when the enemy attacks us for political reasons — as with al Qaeda, Hezbollah, or Hamas — with the violence regularly possessed by nations. But the use of the military is not appropriate against criminals, even powerful cartels. Criminal gangs can only become legitimate military targets when they act as the arm of a hostile foreign government, as the Trump administration has claimed with the Venezuelan drug-running boats.

Political rhetoric, unfortunately, blurs the line between war and crime. The “war on drugs” or the “war on poverty” invoked the language of military campaigns to fight perennial social problems, not concrete enemies. As former CIA Director James Woolsey has observed, a “war against terrorism” makes as little sense as a “war against kamikazes.” The United States is not at war with every criminal or every terrorist who uses violence. It is at war only with those enemies—like al Qaeda on September 11, or a cartel acting as the arm of a hostile regime—whose organized political violence makes them proper objects of war. Maintaining this distinction enables the government to address genuine foreign threats with military force, while ensuring that ordinary domestic activities remain exempt from the extraordinary powers of war.

Terrorism as War, Not Crime

If the Soviet Union had carried out a 9/11-like attack during the Cold War, no one would have doubted that the United States was at war. Yet because the perpetrators were not a state, critics of the Bush administration’s terrorism policies argued that terrorism is just a crime. Terrorism, even as destructive as the 9/11 attacks, by definition cannot justify war, because we are not fighting another nation, critics have contended. Former Clinton Deputy Attorney General and Harvard law professor Philip Heymann argued that “war has always required a conflict between nation states.” Former Senator and presidential candidate Gary Hart and historian Joyce Appleby put the view thus: “the ‘war on terror’ is more a metaphor than a fact. Terrorism is a method, not an ideology; terrorists are criminals, not warriors.”

If 9/11 did not trigger a war, then the United States would have been limited to responding to al Qaeda with law enforcement and the criminal justice system. But those who would limit the nation’s response to terrorism misunderstand the line that separates crime from war. War is not just limited to nation-states. Organized violence undertaken against the United States because of our policies — the kind carried out by al Qaeda, Hamas, or Hezbollah — falls into the realm of war. Profit-driven brutality, such as the violence of drug cartels, remains in the realm of crime.

Unlike crime, war is forward-looking. In war, nations use extraordinary measures to prevent future attacks on their citizens and territory. Law enforcement, by contrast, is a backward-looking enterprise; it focuses on solving crimes that have already occurred in the past. Our military and intelligence agents seek to stop deadly, foreign attacks that may happen in the future. The difference in purpose dictates the use of different tools. The FBI and the DEA — not the U.S. armed forces — have primary responsibility for interdicting drug smuggling (although the military sometimes plays a supporting role). They seek to disrupt the operations of drug cartels with traditional tools of law enforcement: collecting evidence, arresting suspects, and prosecuting felons. An investigation typically occurs only after a crime has been committed. Deadly force may be used only if necessary to defend the law enforcement agent’s life, or another’s, against an imminent threat to life or limb.

War, by its nature, is violence on a large scale, undertaken for political reasons by a foreign state or entity, which requires a military response. Political objectives have always defined war. The United States went to war in World War II to achieve regime change in Germany and Japan; they went to war to conquer territory. We resorted to armed force in Korea, Vietnam, and Panama, among other places, to stop the spread of enemy ideologies or to remove hostile regimes. Like a nation, a terrorist group conducts attacks that are highly organized, military in nature, and aimed at achieving ideological and political objectives. A terrorist group might resort to crime for funding, such as stealing money or defrauding charities; however, terrorist groups typically use the money for military and intelligence efforts rather than merely accumulating wealth. That political purpose makes terrorism a proper subject for war.

Hamas and Hezbollah illustrate why terrorist groups, though not states, can rise to the level of enemies. Both conduct sustained campaigns of political violence against Israel, backed by a state sponsor in Iran. Their tactics mirror those of nation-states, with coordinated military operations, territorial control, and ideological missions. As senior Hamas official Ghazi Hamad vowed in an interview about the October 7 massacres, “We must teach Israel a lesson, and we will do it twice and three times. The al-Aqsa Deluge is just the first time.” Hamas leader, Yahya Sinwar, a chief architect of the October 7 attacks, called civilian casualties in Gaza a “necessary sacrifice” for Hamas’s struggle. And Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah called to “activate and boost all forms of the resistance against the Israeli normalization,” and “Israel, the cancerous tumor, is to be wiped out.” Like bin Laden, terrorist leaders in the Middle East erase the line between civilian and military, thereby proving that politically motivated, large-scale organized violence falls within the realm of war and not the criminal justice system.

Cartels as Crime, Not War

An enemy’s political objective distinguishes war from crime. Crime persists at a level that society will never completely eradicate. Crime is generally committed for personal gain or profit rather than a political goal. Drug cartels employ murder, robbery, and violence to create a distribution network, grab turf from other gangs, intimidate rivals or customers, and even retaliate against law enforcement. National security threats, such as terrorist groups, might resemble organized crime, but the Mafia and drug cartels are unconcerned with ideology and are primarily out to satisfy their greed.

According to the Supreme Court, a nation at war is entitled to detain as enemy combatants those “who associate themselves with the military arm of the enemy government, and with its aid, guidance and direction enter this country bent on hostile acts.” A nation at war may kill members of the enemy’s armed forces. But law enforcement personnel may only use force in defense of their lives or those of others. Once captured, an enemy combatant can be detained until the end of the conflict. Combatants have no right to Miranda protections, a lawyer, or a criminal trial to determine their guilt or innocence under the laws of war. They are simply being held to prevent them from returning to the fight.

But crime can transform into war when cartels cease to act independently and instead operate as instruments of a hostile regime. At that point, the conflict is no longer with criminal organizations alone but with a sovereign state. That may be the case with Venezuela, as the Trump administration has advanced in court. In his March 15 proclamation invoking the Alien Enemies Act, President Trump declared that the Tren de Aragua drug cartel was “conducting irregular warfare and undertaking hostile actions against the United States” and that it “operates in conjunction with Cártel de los Soles, the Nicolás Maduro regime-sponsored, narco-terrorism enterprise based in Venezuela.” He found that Tren de Aragua “has infiltrated the Maduro regime, including its military and law enforcement apparatus.” Based on these findings, the White House concluded that the gang’s activities satisfied the Act’s requirement of “an invasion or predatory incursion” by a foreign nation, allowing for the deportation of Venezuelan nationals.

If substantiated, these arguments would alter the legal and constitutional footing of the U.S. attacks on suspected drug-running vessels in South American waters. The use of military force against Venezuelan cartels would not be an open-ended war on narcotics trafficking; it would instead be part of a conflict with the Maduro regime. Such a conflict would not be a broad, amorphous campaign against the drug trade, which would violate American law and the Constitution, but a war between the United States and Venezuela, in which the drug cartels are acting as irregular forces attached to the Maduro regime.

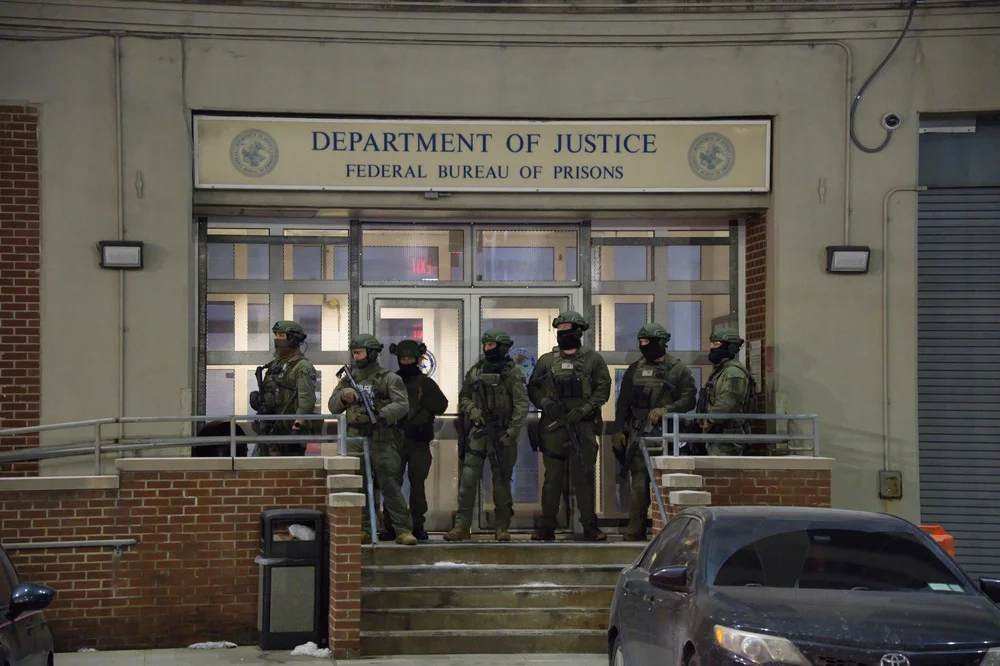

But the White House has yet to provide compelling evidence in court or to Congress that drug cartels have become arms of the Venezuelan government. That showing is needed to justify not only the removals (which were just overturned by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit) but also the naval attacks in the South American seas. Even if the administration satisfies the standards for war, it would open the door to another set of complex problems: Every member, not just of the Venezuelan armed forces but also of the drug cartels, would become a legitimate military target; the U.S. could attack and even occupy Venezuelan territory; and all Venezuelans here would become enemy aliens.

The consequences of war show why the bar for treating cartel activity as an extension of state power must be high. The decision is not about prosecuting criminals, but about unleashing the extraordinary powers of war: detention without trial, targeted killing, sweeping surveillance, even the occupation of territory. These blunt instruments are meant for sovereign enemies, not for persistent social ills. Preserving this line ensures the United States can fight both enemies — terrorists and criminals — without undermining its constitutional foundations. When cartels act alone, their crimes belong in the courtroom. Only when they operate as proxies of a hostile regime should they be treated as enemies on the battlefield. That distinction protects liberty at home while preserving the President’s ability to protect the nation’s security from foreign threats.

September 11 put America on notice. Once, only nation-states had the resources to wage war. Al Qaeda financed its jihad outside the traditional structure of the state and showed how networks of individuals could tap the power to inflict violence that was once held only by nation-states. The pre-9/11 attitude of the United States toward terrorism did not allow terrorist groups to evade the laws of armed conflict once they crossed the line into war. But while we are at war, we must recognize that it is a different kind of war—against a slippery enemy with no territory, population, or uniformed army, able to move nimbly through the open channels of commerce. Hamas and Hezbollah continue the same campaign, sustained by foreign sponsors, aimed not at profit but at political goals. Against such enemies, the United States and other Western nations have the legal right to rely upon the full powers of war.

The Trump administration is correct that illicit drugs are inflicting more harm on the U.S. than most armed conflicts have. More than 800,000 Americans have died of opioid overdoses since 1999. Drug-caused deaths remain at historic highs, with an estimated 76,000 perishing from fentanyl in 2023 alone (though this figure dropped to 48,000 last year), far outpacing American personnel killed in recent wars, such as Iraq (4,418), Afghanistan (2,349), and even Vietnam (58,220) and Korea (36,574).

But the Trump administration’s recent attacks on drug-running boats in South American waters risk crossing the line between crime-fighting and war. By default, drug cartels begin on the crime side of the line. Their brutality is real, and their toll is staggering. But their purpose is greed, not politics. To confuse them with wartime enemies is to misuse the tools of war, erode constitutional limits, and endanger liberty at home. Only when a cartel becomes the instrument of a hostile regime—as may be the case with Venezuela—do the legal rules change. Then the conflict is not with a social problem, but with another nation.

To make informed policy choices, it is essential to understand the differences between war and criminal justice, as well as the appropriate uses of each. War is too important to be the subject of partisan politics; it invokes powers too extraordinary to be used against crime. Maintaining the distinction between war and crime enables the United States to address foreign threats while ensuring that war remains in its proper context.

John Yoo is a senior research fellow at the Civitas Institute, and a distinguished visiting professor at the School of Civic Leadership at the University of Texas at Austin. He is also the Emanuel Heller Professor of Law at the University of California at Berkeley where he supervises the Public Law and Policy Program among other programs at Berkeley Law.

Politics

.webp)

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

This article explores Leo Strauss’s thoughts on Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1954 “Natural Right” course transcript.

%20(1).avif)

Long Distance Migration as a Two-Step Sorting Process: The Resettlement of Californians in Texas

Here we press the question of whether the well-documented stream of migrants relocating from California to Texas has been sufficient to alter the political complexion of the destination state.

%20(3).avif)

Who's That Knocking? A Study of the Strategic Choices Facing Large-Scale Grassroots Canvassing Efforts

Although there is a consensus that personalized forms of campaign outreach are more likely to be effective at either mobilizing or even persuading voters, there remains uncertainty about how campaigns should implement get-out-the-vote (GOTV) programs, especially at a truly expansive scale.

There's a Perception Gap With the U.S. Economy

As we approach another election cycle, it’s worth asking: what’s real, what’s political theater, and what does it all mean if Democrats regain control of the House?

International Law Is Holding Democracies Back

The United States should use this moment to argue for a different approach to the rules of war.

Trump purged America’s Leftist toxins. Now hubris will be his downfall

From ending DEI madness and net zero to securing the border, he’ll leave the US stronger. But his excesses are inciting a Left-wing backlash

California’s wealth tax tests the limits of progressive politics

Until the country finds a way to convince the average American that extreme wealth does not come at their expense, both the oligarchs and the heavily Democratic professional classes risk experiencing serious tax raids unseen for decades.

The Venezuela Symposium

Eight Latin American contributors discuss Venezuela's future and its wider consequences for the region.

Venezuela Post-Maduro

Indeed, for many, the Venezuelan situation seemed to have no other way out, since everything had already been tried without success. It was about time.