The Declaration’s Reconciliation of Populists and Constitutionalists

The Declaration would have both parties collaborate in restoring popular sovereignty and constitutional government against common enemies.

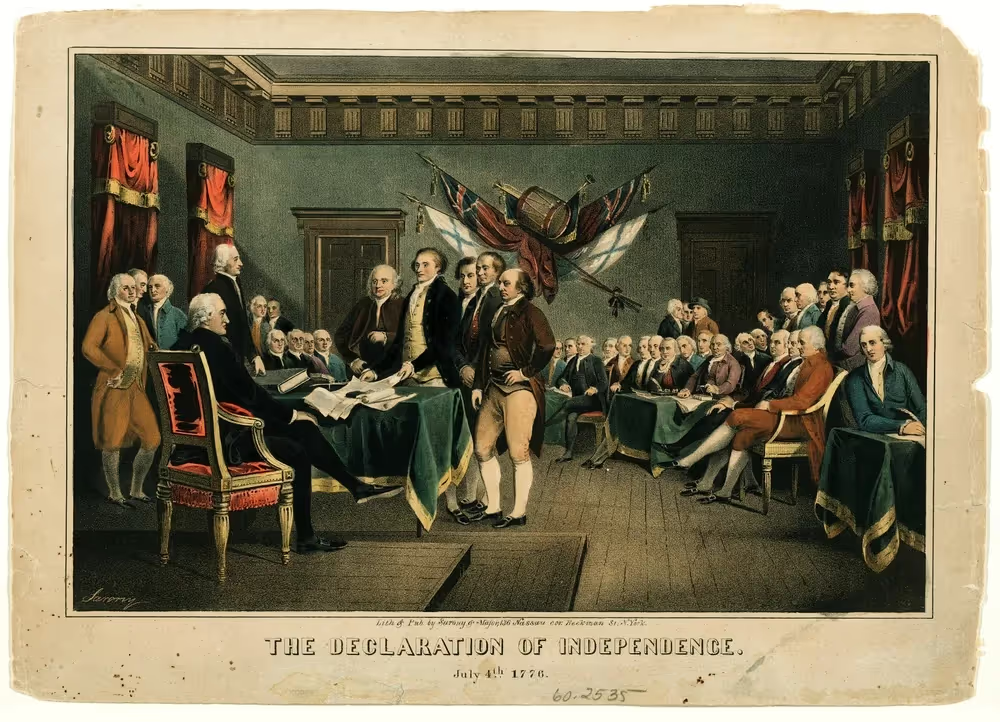

The Declaration of Independence is arguably the greatest example of coalition-building in American history. It combines eminent men – “the Representatives of the united States of America” – and the people – “the good People of these Colonies” – working (and fighting) together for the sake of resisting encroaching despotism and achieving independence, with the prospect of a free government for a free people the terminus ad quem of the grand collaboration. There are lessons for us today in this, especially those of us who see in the previous administration and its allies enemies of the republic and who wish for a freedom-coalition in our own day.

In what follows, I will draw out some lessons in this regard from the Declaration. My title indicates the chief lesson, which speaks to what today are called “populists” and “constitutionalists.” The Declaration would have both parties collaborate in restoring popular sovereignty and constitutional government against common enemies. Given human nature and the character of the two parties, this will take some mutual forbearance and a baseline of respect. As encouragement to these sentiments, I recall Benjamin Franklin’s famous saying, that we “must hang together, or hang separately. “

The Ends of Free Government

The Declaration outlines its desired outcome, a government of and for a free people, in several places throughout the document, most prominently in its second part. There, what I have elsewhere called “the principles of politics” are enunciated. These famously include the pediment of a free society and government, the equality and “unalienable” or natural rights of “all men”. But the principles extend beyond these fundamental human truths to indicate what a government erected on this basis should consist of. It is a work of high political intelligence and art, combining the contributions of political theorists, statesmen, and the sovereign people.

Here is the relevant passage from the second part:

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their

just powers from the consent of the governed, - That whenever any Form of Govern-

ment becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to

abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles

and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect

their Safety and Happiness.

To start in a teleological vein: properly organized government has three goals (not just one). In addition to portecting natural rights (“these ends”), it is explicitly aimed at two “popular” goals: the safety and the happiness of the people. This complexity entails that the politics of a free people will always be contentious, as they debate the nature of these defining objects and their proper relationships, not only in principle or theory but in practice, in the changing circumstances of the day. Such ongoing debates are ‘baked into’ the Declaration’s schema of government. Efforts to squelch this debate are, therefore, rightly stigmatized as illegitimate because directed against both components of liberal democracy, individual freedom of speech and democratic debate. Having suffered from the censorship regime of the previous administration and its conniving allies, populists and constitutionalists can come together as strong advocates for free speech.

Popular Sovereignty

The passage also indicates that the people is the alpha as well as the omega of legitimate government. Government’s powers – its “just powers” – come from it. Nor is it only at the beginning that the people is the government’s sovereign. The entire third part of the document, the list of twenty-seven “usurpations” and “injuries” of the king (and parliament) against the colonists, indicates an observant, discerning, and judging populace when it comes to the deeds and character of government. In the passage cited above, one notes that two sorts of rights are asserted: the unalienable rights of individuals and “the Right of the People to alter or abolish” a “Form of government” that it finds acting counter to the purpose or purposes for which it is established and “to institute new Government”. (Other passages in the document indicate other rights of the people, such as “representation” in government, or the common law right to “Trial by Jury”.) Source, vigilant observer, and final arbiter: the people of the Declaration are never the government’s subjects to do with as it wishes. That is the classical definition of despotism.

As the preamble makes clear, the people has its own reality, its own legitimacy and standing:

When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, … .

Warranted by Nature and God, under them, the people is sovereign. In addition to what we saw in the previous paragraph, there is another area of common ground between the parties: popular sovereignty. Populists feel it in their (sometimes aggrieved) bones and constitutionalists more coolly echo their founding document: “We the People … .”

Well-organized Government

As sovereign, the people determine what is necessary and best for it to preserve its precious liberties, its independence, and its capacity for self-determination or self-government. In the eyes of the Declaration, well-organized government is the first and chief desideratum. The passage cited above, therefore, indicates essential components of its construction. Free government is a matter of “principles” and “powers,” “form[s]” and “Form,” rightly arranged to serve its various purposes (including representation). Here, constitutionalists can make an essential contribution to a sovereign people. As thinkers as different as Aristotle and Machiavelli have taught, a free people needs to repair regularly to its first principles, moral and political. Constitutionalists can provide the necessary “constitutional reminder” to a preoccupied, sometimes headstrong, people. And while constitutionalists rightly turn to the Federalist Papers or the judicial opinions of John Marshall to do so, this can be “tee’d up” by a close reading of the theory of government affirmed and sketched in the Declaration.

Questions and (Some) Answers

Government is based on “principles” – what are they? Government is a matter of “powers” – what are they? Government is a formal matter, a matter of forms and Form. What is a governmental form? What is the Form of a well-organized government? Alas, here we cannot retrace the entirety of the Declaration’s vision of government, which would require reading the entire document, but a few instances can indicate that there are answers to these questions. The third part of the document, with its list of monarchical usurpations and injuries, is especially revealing in this regard, as abuse presupposes use, or, more literally: “injury” and “usurpation” imply “rightful treatment” and “staying within proper bounds” of powers and forms.

According to the Declaration, King George has violated numerous principles of right government. Perhaps most ominously, he has violated the principle of the subordination of the military to civil authority, but he has also violated the great principle of the division of powers by ignoring or overriding colonial legislatures and attempting to undermine judicial independence in the colonies. Here, we have attempts at the modern, or Montesquieuan, definition of tyranny: all powers concentrated in one set of hands.

“Powers” – at least “just powers” – come to the government from the sovereign people. Here again, the list of abuses can help in understanding the term. Reading it indicates that the chief powers of government are those of classical liberalism and British practice: executive, legislative, and judicial powers. The list also shows the primacy of the legislative power or powers, as the first seven items pertain to law, legislation, and legislative bodies, with other subsequent mentions. Given the Declaration’s principal interest in law and legislative action (which is quite remarkable, given its chief target and stated purpose), constitutionalists could take the opportunity to instruct populists that the primacy of executive action is not the preferred way of the Declaration; and both could join together to work to restore Congress as the chief organ of representative government.

Here, again, one would expect the populists to contribute vigor and heat, while the constitutionalists to more coolly consider the demands and the execution. If such efforts at restoring congressional primacy are to be effective, however, a certain visible sympathy with the people’s concerns and a certain rhetoric on the part of constitutionalists is required. No one likes a scold. Jefferson prepared the American people for the Declaration with his earlier "Summary View of the Rights of British America."

The Administrative State and the Deep State

One thing that should bring the two parties together is the double curse of the administrative state and the deep state. The first has long been known and criticized in conservative circles as violating the separation of powers, while the second, first brought to attention decades ago by out-of-the-mainstream members of the left, now has been publicly exposed in its nefarious labyrinthine character by DOGE, Michael Benz, Michael Shellenberger, and others. There is no need to delve into their intricacies here, but rather to point out that both states, in different yet complementary ways, deeply undermine the government's responsibility to the electorate. By definition, constitutionalists must be aghast at such deforming barnacles on the ship of state, while the sovereign people can rightly hate those who thus deny its declared will and rightful sovereignty. Together, both can declare: delendae sunt!

Here too, one can expect tensions and disagreements, such as over priorities, means, or legislative or executive strategy. However, while these important matters need to be hashed out, the common goal must not be lost sight of: restoring the instruments of constitutional self-government to the sovereign people. Here is a cause Big Enough, Important Enough, to temper, if not completely overcome, the differences between populists and constitutionalists. In a particular way, on the 4th of July, we can all recall that that Cause, the reconciliation of popular sovereignty and constitutionalism, is the defining Cause of America.

Paul Seaton, an independent scholar, is the translator of The Religion of Humanity (St. Augustine Press) and the author of Public Philosophy and Patriotism: Essays on the Declaration and Us (St. Augustine Press).

Constitutionalism

Amicus Brief: Hon. William P. Barr and Hon. Michael B. Mukasey in Support of Petitioners

Former AGs Barr and Mukasey Cite Civitas in a SCOTUS Brief

Rational Judicial Review: Constitutions as Power-sharing Agreements, Secession, and the Problem of Dred Scott

Judicial review and originalism serve as valuable commitment mechanisms to enforce future compliance with a political bargain.

Supreme Court showdown exposes shaky case against birthright citizenship

Supreme Court will hear challenges to Trump's order ending birthright citizenship, testing the 14th Amendment's guarantee for babies born in America.

Slavery and the Republic

As America begins to celebrate its semiquincentennial, much ink has been spilled questioning whether that event is worth commemorating at all. Joseph Ellis’s The Great Contradiction could not be timelier.

Two Hails For The Chief’s NDA

Instead of trying to futilely plug the dam to stop leaks, the Court should release a safety valve.

.avif)

.avif)