Reagan’s Trade Doctrine

Reagan was a prudent proponent of free trade who understood that the choice was between actual alternatives, not imagined ones.

Until recently, Ronald Reagan was heralded as a president committed to free trade, lowering taxes, and deregulation. This has started to change as New Right thinkers have tried to create continuities between Reagan and Donald Trump. Some of these connections are legitimate, but others are absurd. New Right thinkers such as Oren Cass have even gone so far as to label Reagan a protectionist due to his negotiating of Japan’s Voluntary Export Restraint (VER). While they condemn the erraticism, these partisans tout the VER as a success of protectionism and offer it as a justification for Trump’s second-term tariff policy. Not only is this interpretation misleading, but it is also false and belies either a fundamental misunderstanding or an outright lie.

To set the record straight, we must answer three questions:

1) Was Reagan a protectionist?

2) What were the effects of the VER?

3) How do Reagan and Trump truly compare?

The answer to these questions reveals simple truths. Reagan was far from a protectionist; however, he was a prudent proponent of free trade who understood that the choice was between actual alternatives, not imagined ones. The VER was not a good policy and should not be emulated by anyone seeking to promote American industry and prosperity. While there are some similarities between Reagan and Trump, namely their shared conviction that government policy often impedes progress, there are also stark differences, and it is clear that Trump is not a successor of Reagan.

Was Reagan a Protectionist?

Reagan’s commitment to free trade cannot be overstated. However, we must also understand the context in which he made these decisions. The US economy, particularly the auto industry, was in a very rough spot when he took office in 1981. After decades of low gas prices, which made driving big, heavy, less fuel-efficient cars of the sort made in Detroit affordable, an oil crisis beginning in 1973 and amplifying in late 1978 hit American car drivers especially hard. The oil crisis was so severe that it kicked off a series of mini recessions in 1980 and again in 1981.

At the same time, Japan had begun exporting cars to the US, and in 1980, Japanese-made cars comprised over 20% of the US market. Their cars had three advantages over domestically produced cars: they were more fuel efficient due to their smaller size and weight-conscious construction, they were cheaper than American cars on the road, and they required significantly fewer repairs than their American counterparts. In many ways, they were superior vehicles. As a result, they were quickly supplanting US cars. Detroit’s Big Three automakers: Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler (now Stellantis) were languishing and were forced to lay off thousands of workers.

Protectionist measures were already brewing in Congress, with the Democrats ready to pass a bill imposing severe import quotas on Japanese automobiles to protect the domestic car market. Reagan recounted his dilemma in his autobiography “Although I intended to veto any bill Congress might pass imposing quotas on Japanese cars, I realized the problem wouldn’t go away even if I did.” By “the problem,” Reagan was not referring to “Japanese imported cars.” He referred to the demand for protectionist measures from Congress and the union autoworkers.

Reagan knew that vetoing bills would only forestall the inevitable. He also suspected that any protectionist measures that Congress imposed would be severe and recognized that Congressional actions are easy to pass but difficult to rescind. If he didn’t act quickly, the US would suffer from the sting of protectionism for a long time. At a meeting, Vice President George H.W. Bush reportedly remarked, “We’re all for free enterprise, but would any of us find fault if Japan announced without any request from us that they were going to voluntarily reduce their export of autos to America?" Thus came the idea of a voluntary export restraint. Reagan quickly dispatched his Trade Representative, Bill Brock, to help with the discussions, which culminated in a meeting in the Oval Office on March 24th with the Japanese foreign minister where, in Reagan’s words, “I told him that our Republican administration firmly opposed import quotas but that strong sentiment was building in Congress among Democrats to impose them. ‘I don’t know if I’ll be able to stop them,’ I said. ‘But I think if you voluntarily set a limit on your automobile exports to this country, it would probably head off the bills pending in Congress and there wouldn’t be any mandatory quotas.’”

In the end, Japan agreed to voluntarily restrict the number of cars it exported to the US. This agreement was initially for three years but was extended numerous times until the VER was lifted in 1994.

Understanding the context surrounding decisions and actions is essential. For example, if all we knew about someone was that they had stuck a knife into another person, we might initially believe that person to be a monster who should be locked away. But if we take a step back and realize that this person is a doctor in an operating room performing life-saving surgery, we can readily understand from the context that they are not a monster; far from it, they are attempting to heal, not to harm. Likewise, Reagan was committed not to protectionism but to preventing protectionism precisely because he knew and understood its harms.

What Was the Effect of the VER?

Of all the writers championing the VER as a paragon of protectionist policies “done right,” none hold a candle to Oren Cass. Cass points out that the VER saved the domestic auto industry while encouraging foreign auto makers to invest in America, particularly the American South. He says this encouraged manufacturing jobs throughout the country, revitalizing all that is good, true, and American, and ushering in a new era of prosperity for America and its people. It is important to note that for Cass to be correct, it must be the case that the increased manufacturing job growth, the increased foreign investment, and prosperity would not have happened without the VER.

Unfortunately for Cass, this is not the case.

Looking at job growth data, for example, the short term effect was quite positive. A 1985 International Trade Commission report says that “it is likely that the [VER] added about 5,400 jobs to U.S. automobile employment in 1981, and by 1984, the [VER] was responsible for a total of 44,000 additional jobs in the domestic industry.” In the interest of fairness, the report notes that “if the employment gains in the steel industry and other supplier industries were added to these numbers, the gains in employment would be significantly higher.”

This is trivially obvious to anyone with even a cursory understanding of economics. Protectionist policies do lead to increased job growth, at least in the short run, if only because contracts and production processes cannot shift on a dime due to transaction costs. However, over the medium to long run, when producers have time to renegotiate contracts and change production processes, the results are often harmful for the industries that are being “protected” in the first place.

The domestic automobile industry during the 1980s and 1990s illustrates this. Freed from the pressures of foreign competition, the domestic auto industry’s methods and practices calcified around the idea that Americans would purchase mid-size and large-car models. After all, while Japanese cars were still available, they were becoming harder and harder to come by. By contrast, Japanese automakers continued to invest in improving quality. By 1990, the quality gap between domestically made cars and Japanese cars (as measured by how frequently repairs were needed) had grown even larger.

During the 90s, the Big Three were forced to close 42 of the 63 automotive assembly plants, resulting in tens of thousands of job losses in the industry the VER was supposed to protect. The reason for this is simple and easy to understand: Japanese cars were already better and more affordable than their domestic counterparts in 1981. Because the domestic car industry squandered the opportunity to make crucial adjustments to their fleets, Americans started buying more imported cars. Rather than short-term pains begetting long-term gains, the short-term pains of higher car prices led to greater long-term pains of reduced employment.

When it comes to foreign direct investment, the picture is even worse. At first blush, it would be silly to imagine that foreign firms would invest billions of dollars in manufacturing in response to what was initially a short-term, voluntary restraint on the part of Japan. The profit margins on factories are small and can take decades to pay off. But the reality is that any increased manufacturing of foreign cars in the US was already in the works before the VER was even thought of, let alone enacted.

This is borne out by examining history. Volkswagen, for example, began building manufacturing plants in the US in 1978. Honda built its first plant in the US in Ohio in 1979 and, after years of success there, announced plans to build more plants between 1982 and 1986.

The reason for this is simple: it made economic sense to do so. However, it was not due to the VER. A 1990 report by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve notes that “the production cost differentials between [Japan and the US] have narrowed. One industry analyst has estimated that as of late 1989, an auto can be built at a transplant costing $200 less than one built in Japan and delivered in the United States.” At the same time, due to changes in exchange rates and wage rates in Japan, labor was becoming more expensive in Japan than in the US. Ironically, Japan was looking to offshore manufacturing jobs to the US, where labor was cheaper.

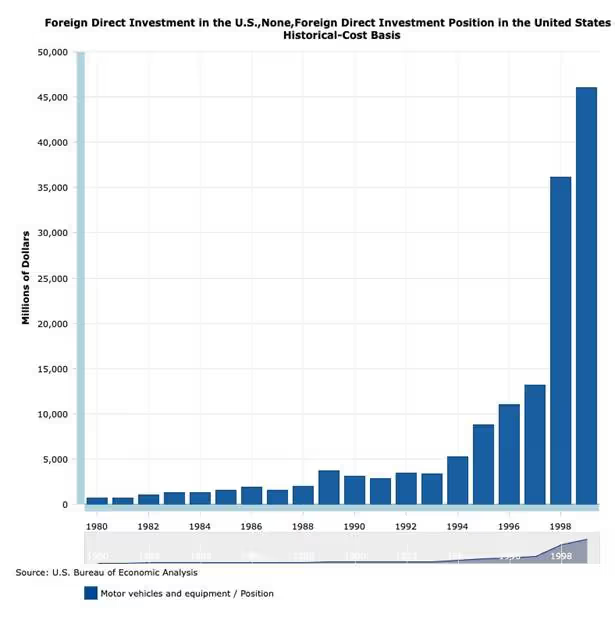

We can see this most clearly by examining the Bureau of Economic Analysis data on foreign investment in the “motor vehicle and equipment” sectors. In 1981, that figure was about $652 million. By the time the VER ended in 1994, that figure was $5.3 billion - a 713 percent increase over the years of the VER. However, in the five years after the VER ended, foreign investment in this sector increased by another 770% (to a staggering $46.1 billion) in 1999. Two major factors contributed to the increased foreign investment in 1994: the end of the VER and the “Republican Revolution,” whereby then-US President Bill Clinton had to contend with a Republican Congress. One issue where both parties agreed on was trade liberalization. As international trade became more liberalized, foreign investments poured into the US.

Reagan and Trump: Similarities and Differences

Much like today’s administration, the Reagan administration took issue with other nations imposing “barriers to our exports and unfairly [subsidizing] their own industries”. It sought to “work to prevent such unfair trade practices.” President Trump made this a central theme in his second presidency, emphasizing that other countries have been “ripping us off” for decades.

Unlike the current administration, however, Reagan insisted that the best response was entrepreneurship, lower taxes, and deregulation, not protectionism. During the 1980 campaign, the Reagan camp compiled the candidate’s positions on various issues. On trade, the campaign emphasized that “Governor Reagan believes that it far better serves our interests, and those of the world, to aggressively pursue a reduction in foreign nations’ trade barriers rather than erect more barriers of our own.” In short, Reagan recognized that protectionism would harm American consumers by raising prices, American manufacturers through higher costs, and stifling innovation, and would make us less competitive on the global stage, not more.

This marks a clear difference between the two administrations. Looking at the Great Seal of the United States, we can see that Reagan chose the olive branch by tearing down regulations we had placed on ourselves, which inhibited our manufacturing sector. This made it easier for other countries to import our goods, rather than making it more difficult for others to export to us. Reagan sought to reinvigorate the American economy by helping American workers, not by punishing American consumers for buying foreign goods.

By contrast, Trump has chosen the arrows, as evidenced by his desire to “reciprocate” the trade policies of other nations. Indeed, in less than three months, Trump has upended the post-World War II trade liberalization that contributed to unprecedented economic growth at home and abroad and massive declines in absolute poverty worldwide.

Although Reagan and Trump share a belief in deregulation and lower income taxes, they fundamentally disagree on trade, immigration, and America’s role in the world. During the debates leading up to the 2016 election, when asked, every other Republican hopeful praised Reagan and explained how they would try to emulate him and his policies. When Trump was asked about Reagan, in typical Trump fashion, he exclaimed that Reagan had admired him. Unfortunately, what one of us described in 2020 still holds

“From Trump’s family separation and detention policy at the border, to his trade wars with half the world, to his assault on international institutions, to his reckless disregard for the separation of powers, Trump has redefined conservatism. He has moved away from Reagan-era Republicanism–a belief in the rule of law, free trade, civil society, decentralization, and working through international organizations abroad.”

Trump partisans and apologists will undoubtedly try to spin Trump’s erratic policies as best they can, but they need to leave Reagan out of it. The simple reality is that there is no way that the fortieth president would have endorsed or condoned the actions of the forty-seventh.

Dave Hebert is a senior research fellow at AIER. He was formerly a professor at Aquinas College, Troy University, and Ferris State University. He has also been a fellow with the U.S. Senate Committee on the Budget and has worked for the U.S. Joint Economic Committee.

Marcus Witcher is a Teaching Assistant Professor of Economic History at West Virginia University, where he also serves as Manager of Undergraduate Programs for the Knee Regulatory Research Center. His first book, Getting Right with Reagan: The Struggle for True Conservatism, 1980-2016, was published by the University Press of Kansas in 2019 and was a finalist for the Reagan Foundation book award.

Economic Dynamism

.jpg)

Do Dynamic Societies Leave Workers Behind Culturally?

Technological change is undoubtedly raising profound metaphysical questions, and thinking clearly about them may be more consequential than ever.

The War on Disruption

The only way we can challenge stagnation is by attacking the underlying narratives. What today’s societies need is a celebration of messiness.

Unlocking Public Value: A Proposal for AI Opportunity Zones

Governments often regulate AI’s risks without measuring its rewards—AI Opportunity Zones would flip the script by granting public institutions open access to advanced systems in exchange for transparent, real-world testing that proves their value on society’s toughest challenges.

Downtowns are dying, but we know how to save them

Even those who yearn to visit or live in a walkable, dense neighborhood are not going to flock to a place surrounded by a grim urban dystopia.

The Housing Crisis

Soaring housing costs are driving young people towards socialism—only dispersed development and expanded property ownership can preserve liberal democracy.

Oren Cass's Bad Timing

Cass’s critique misses the most telling point about today’s economy: U.S. companies are on top because they consistently outcompete their global rivals.

Blocking AI’s Information Explosion Hurts Everyone

Preventing AI from performing its crucial role of providing information to the public will hinder the lives of those who need it.

.jpeg)

.jpg)