Free Markets, Economic Growth, and the Restoration of Civic Culture

America’s free market democracy and constitutional republic is, at its core, the most effective system of cooperation ever created by humans.

The countdown to our nation’s 250th birthday is officially underway. But when it comes to the current state of American civic culture, there will be little to celebrate.

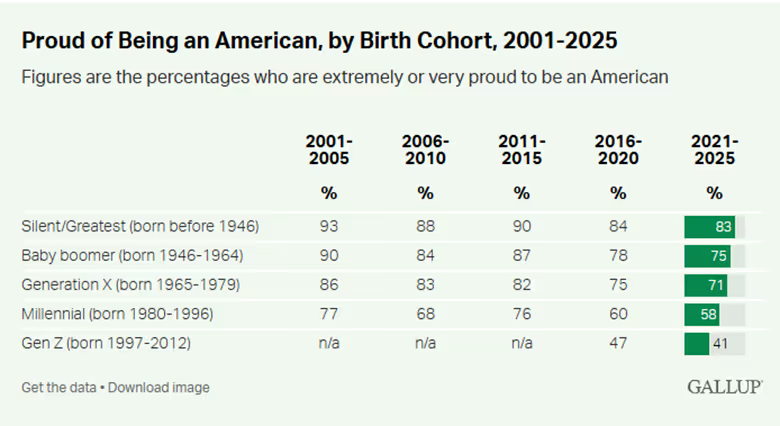

A Gallup poll released last week confirmed what most of us already knew. There is a growing divide across party lines regarding patriotism.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/692150/american-pride-slips-new-low.aspx

Even more disturbing is the finding that patriotism is generally trending downward over time, resulting in the youngest Americans being the least patriotic.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/692150/american-pride-slips-new-low.aspx

These poll results are hardly indicative of a healthy civic culture. Pride in being an American should be derived from ideas, principles, and beliefs that run far deeper than political party affiliation. They should also be far too robust to fade merely with the passage of time.

We’ve been deeply divided in the past, of course. But those periods of division pertained to specific issues like slavery or the Vietnam War. Today, what divides us is more troublesome. It is becoming increasingly apparent that it is the result of our having increasingly incompatible visions for what our country should look like.

These conflicting visions are derived from two very different premises about the nature of the rise of the West and America. The first premise is well known, but is even more pernicious than most people realize. As for the second premise, few people have ever heard about it. This is tragic since it’s the key to understanding why America is indeed an exceptionally good country.

The first premise is the oppression thesis. It holds that the rise of the West and America is largely the story of ever more effective oppression of the weak by the strong. This is now so deeply embedded in our institutions, the story goes, that both the oppressed and the oppressors are largely unaware of it. So the oppressed must be taught to recognize what they are owed, and the oppressors must be taught their moral obligation to provide it.

The problem isn’t that too few people are aware of the oppression thesis. The problem is that those who reject it don’t seem to know what to do about it.

The oppression thesis promotes “us versus them” thinking and therefore tribalism that destroys trust. It also taps into our disgust for injustice, allowing those who accept it to view themselves as morally superior because they are either deserving victims or victimizers who are at least honest enough with themselves to be eager to atone.

But what most people don’t understand is that it also provides a thread that ties together much of the anti-American content that has crept into almost every subject in American K-12 and higher education. It is the foundation of WOKE, DEI, CRT, and other fads. This produces meta-narrative coherence that is particularly attractive to young minds.

The growing cultural influence of the oppression thesis is remarkable because it withers under scrutiny. It implies that ours is a system in which bullies become rich by taking from the poor. However, in America, the quality of life for the poor has consistently improved over time. Obviously, we can’t all become richer at the same time by stealing each other’s chickens. Yet something like that is what you have to believe if you follow the oppression thesis to its logical conclusion.

We can restore America’s civic culture by shifting to an almost entirely unknown but infinitely more plausible premise, one that makes common sense and, when taken to its logical conclusion, it comports with economic reality. It also provides a simple explanation for why we should be proud to be Americans.

That premise is the cooperation thesis. It holds that the rise of the West and America is largely the story of ever more effective cooperation being catalyzed by ever freer people transacting over ever better markets. In reality, it is cooperation, not oppression, that is so deeply embedded in our way of life that for us it is like water to fish. And as the old saw goes, fish are always the last to discover water.

In a simple society, the power of cooperation is readily apparent in a tangible way. For example, I spear five fish alone, and you do too. But when I herd the fish past you while you do all of the spearing, we get 14. The extra 4 fish – the cooperative surplus – makes it possible for both of us to be made better off at the same time, so no coercion is required. Freedom and cooperation go hand in hand.

But in an extensive and highly specialized market society, cooperative gains are like nuclear forces that hold atoms together: unfathomably powerful and incredibly important for understanding the nature of the physical world, but not readily apparent to the casual observer.

How does cooperation explain the rising quality of life in a complex social world, say for the poor in America over the last 150 years?

The rich save a significant portion of what they earn. In doing so, they provide funds for the purchase of plant and equipment (capital). This capital increases profit by increasing the productivity of labor.

If the number of firms was fixed, this might end up reducing the demand for, and therefore the wages of, labor. But in a free market society, the number of firms is not fixed. When capital increases profits, other entrepreneurs create new firms to make profits as well. That increases the demand for labor, which, in turn, increases wages, making the relatively poor richer, too.

This cooperative gain is hard to see because it arises indirectly through the system. However, in America, it has been the key to creating a good life for an ever-greater proportion of the population over time. Every future voter should deeply understand this story. That begins with teaching, as early as possible, the simple logic of how cooperation benefits everyone.

Many have opposed variants of the oppression thesis over the years. However, better than opposing the oppression thesis is replacing it with the cooperation thesis. Doing so also gives children and young adults something to be for rather than only something to be against.

Oppression is, of course, an important part of our story. But America thrived despite oppression, not because of it. To have real output per capita rise, something other than the strong taking from the weak is required, since that doesn’t increase output. Cooperation provides a plausible explanation. By piling up cooperative surpluses over time, societies can divide an ever larger pie among the same number of people. This produces a condition of increasing general prosperity ad infinitum. Oppression doesn’t do that.

The cooperation thesis also offers a straightforward and compelling explanation for American exceptionalism. No other society has reached the level of development we enjoy because their cultures and institutions do not support cooperation as well as ours. We live in an exceptional society because, as individuals, we are exceptional cooperators who are fortunate enough to live in a culture that supports cooperation exceptionally well.

The oppression thesis has been poisoning our culture. It discourages our traditional optimism and national pride, and it fosters self-righteous pessimism and a sense of shame for being an American. The quickest path to restoring our civic culture is to render the oppression thesis moot by making the cooperation thesis a central feature of civic education.

Every future voter should be taught “cooperation civics” so they can arrive at the following logical conclusion on their own:

America’s free market democracy and constitutional republic is, at its core, the most effective system of cooperation ever created by humans.

If we want children to grow up to be proud to be American, we should teach them what they need to know to understand for themselves why this statement is true.

David C. Rose is a senior research fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research, author of Why Culture Matters Most (Oxford University Press, 2019), and the co-founder of the American Civics Academy.

Economic Dynamism

The Causal Effect of News on Inflation Expectations

This paper studies the response of household inflation expectations to television news coverage of inflation.

.avif)

The Rise of Inflation Targeting

This paper discusses the interactions between politics and economic ideas leading to the adoption of inflation targeting in the United States.

The Housing Crisis

Soaring housing costs are driving young people towards socialism—only dispersed development and expanded property ownership can preserve liberal democracy.

.jpeg)

America Needs a Transcontinental Railroad

A proposed merger of Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern would foster efficiencies, but opponents say the deal would kill competition.

The Poverty of Vanceonomics

At the core of Vanceonomics is a preferential option for government intervention.

Entrepreneurial Freedom in the Age of AI

The AI economy can lead to a more inclusive economy that permits people the freedom to choose when they work, what they work on, and who they work for.

.jpg)

.jpg)