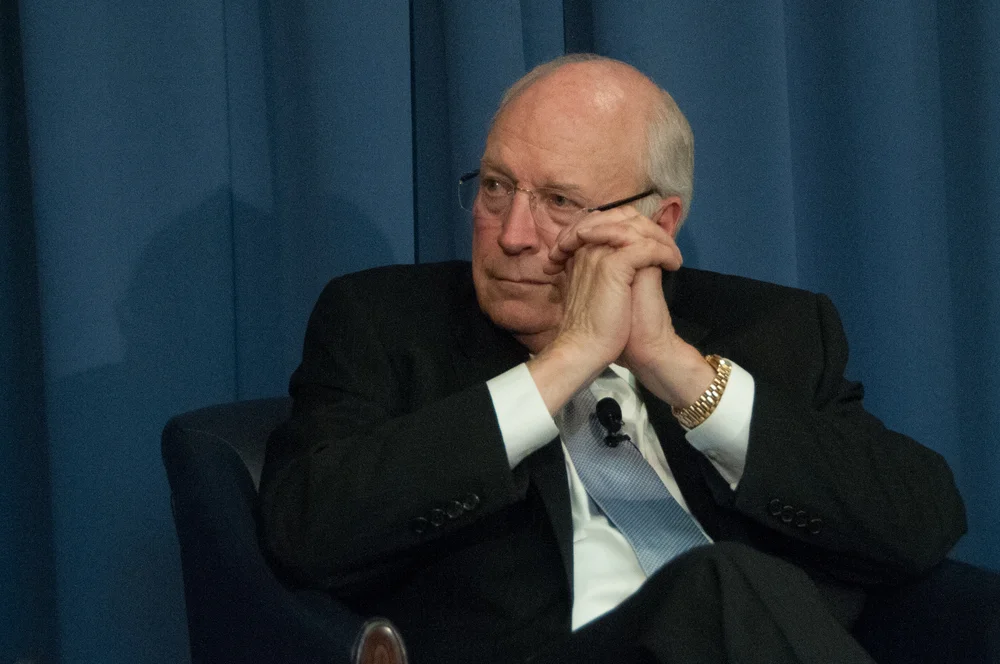

Dick Cheney, Reader

Across a long and storied career, Dick Cheney had a secret weapon: his active engagement with the world of conservative ideas.

Much has been made of the recent death of Dick Cheney, former White House chief of staff, defense secretary, congressman, and vice president. For almost half a century, he was one of the most consequential political figures in American politics. While much has been made of his service and his controversial decisions, one thing that has been insufficiently noted was Cheney’s longstanding interest in conservative books and ideas.

Born in Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1941, Cheney was a reader in his youth, taking in books on World War II and the West, and even reading a book about power lines during his time as a power line worker. After dropping out of Yale, he earned a BA and MA in Political Science from the University of Wyoming. Then, after some graduate work at the University of Wisconsin, he went to Capitol Hill, where he experienced one of the most rapid and remarkable rises in American political history. While on the Hill, he had the good fortune to connect with a young Congressman named Donald Rumsfeld. Rumsfeld made Cheney one of his aides at the Office of Economic Opportunity in the Nixon administration. When Rumsfeld became chief of staff in the Ford White House, he brought Cheney with him as his deputy. When Rumsfeld moved to the Defense Department, Dick Cheney became White House chief of staff in 1974, the youngest chief of staff in history.

Though young, Cheney was a skilled operative in the Ford White House. Ford trusted him to get things done with a minimum of drama. He could also handle sticky situations. One of the most problematic aides in the Ford White House was Robert Hartmann, a former journalist turned speechwriter who was a notorious leaker and pot-stirrer. Hartmann was also Ford’s personal friend, with an office adjoining the Oval Office, giving him access to the presidential toilet, and more importantly, the presidential inbox. It was up to Cheney to dislodge him — delicately. Without mentioning Hartmann’s name, Cheney sold Ford on a private space where Ford could engage in quiet reflection. Ford liked the idea, and when Hartmann came into the office one day, he found the door to his office sealed and his office repurposed.

Cheney was also involved in the Ford White House’s efforts to reach out to and cultivate conservative intellectuals. Rumsfeld hired the Straussian political scientist Robert Goldwin to take on this role, and Goldwin worked closely with Cheney on outreach to conservative thinkers. Goldwin would help arrange seminars for Ford with scholars like Daniel Boorstin, Martin Diamond, James Q. Wilson, and Irving Kristol. Cheney particularly liked Kristol, writing at one point to Goldwin, “I greatly appreciate receiving the stuff you've been sending me... anything that comes in from Kristol or others, I'd love to see.” Cheney would also ask Goldwin to have Kristol provide feedback on specific Ford speeches. Hartman, typically, did not think much of this and dismissively referred to Goldwin as “Rumsfeld/Cheney’s resident ‘intellectual.’”

Cheney then became a Congressman from Wyoming, serving for a decade and rising to the position of party whip. Then, he experienced another bout of good fortune, akin to his initial connection to Rumsfeld. Texas Senator John Tower was poised to become Defense Secretary in the George H. W. Bush administration but couldn’t get confirmed because of reports of his excessive drinking. Cheney stepped in as the replacement at a propitious time. He helped guide the military through a successful first Gulf War. After that war, he sent a photograph to Israeli General David Ivry of the destroyed Iraqi nuclear reactor at Osirak. While the US had condemned the 1981 Israeli raid that had destroyed the reactor, Cheney recognized in retrospect how important that Israeli attack had been. He signed the photo with this inscription:

For Gen. David Ivry, with thanks and appreciation for the outstanding job he did on the Iraqi nuclear program in 1981 – which made our job much easier in Desert Storm.

As Defense Secretary, Cheney also established relationships that had lasting consequences. One was with General Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. While Powell was revered by the media, which appreciated his strategic leaking, Cheney was willing to put Powell in his place when appropriate. At one point, he told Powell,

Colin, you’re chairman of the Joint Chiefs. You’re not Secretary of State. You’re not the national security advisor anymore. And you’re not Secretary of Defense. So stick to military matters.

Their contentious relationship would have ripple effects into the George W Bush administration, when Powell’s top aide Richard Armitage would leak the identity of a covert official to the columnist Robert Novak and let Cheney’s top aide Scooter Libby take the fall for it. Powell knew what had happened, but remained silent, a mark of shame against him, while Cheney worked relentlessly to defend his aide and friend.

Cheney developed a more positive and more important relationship with the first President Bush. In 2000, while Cheney was assigned to pick George W. Bush’s vice presidential nominee, Bush’s father encouraged him to look at Cheney. As the elder Bush told his son, “You’ll never have to worry about Cheney going behind your back.” Bush 41 continued to be a fan of Cheney, telling the journalist Hugh Sidey, “George W. Bush is lucky to have Cheney by his side.”

The Democrats and the media seized on Cheney’s influence and effectiveness, painting him as a sort of “Darth Vader” of the Bush administration. The Cheneys were unbothered by this, with Cheney’s talented wife Lynne – herself a respected conservative author – at one point making a joke that the designation “humanizes” him.

Cheney served the Bush administration well in a variety of ways. He was popular among Republicans, making him a useful fundraiser and campaigner. And he performed extremely well in his two Vice Presidential debates, giving a strong performance in the well-regarded debate against Joe Lieberman in 2000, and trouncing John Edwards in 2004. (I served on Cheney’s debate prep team and I was impressed with the way he was willing to have Edwards stand-in Rob Portman thrash him in their practice sessions, and seeing how that made Cheney’s performance improve with each session. Portman had also stood in for Lieberman in 2000, after which Cheney gave him a sign with the inscription, “Rob, you were much tougher than my opponent.”)

Cheney also worked hard to remain well-informed while in the White House. A lifelong reader, he continued to read widely as Vice President, taking in Natan Sharansky’s The Case for Democracy, Jay Winik’s April 1865, and Eliot Cohen’s Supreme Command, among others. He was known in the White House for always having a book nearby. As in the Ford White House, Cheney also made it a habit to bring in writers and intellectuals to share their thoughts and ideas. This time, though, he was not arranging the briefings but receiving them. Throughout his time as Vice President, Cheney engaged in wide-ranging discussions with notable figures such as Fouad Ajami, Bernard Lewis, Nathaniel Philbrick, Edmund Morris, David McCullough, Charles Krauthammer, and Victor Davis Hanson on public policy.

Across a long and storied career, Dick Cheney had a secret weapon: his active engagement with the world of conservative ideas. He always recognized the importance of ideas and those who generated them. That secret weapon served him well through his own decades of service to this country.

Tevi Troy is a senior fellow at the Ronald Reagan Institute and a former senior White House aide. He is the author of five books on the presidency, including The Power and the Money: The Epic Clashes Between Commanders in Chief and Titans of Industry.

Pursuit of Happiness

The Rise of Latino America

In The Rise of Latino America, Hernandez & Kotkin argue that Latinos, who are projected to become America’s largest ethnic group, are a dynamic force shaping the nation’s demographic, economic, and cultural future. Far from being a marginalized group defined by oppression, Latinos are integral to America’s story. They drive economic growth, cultural evolution, and workforce vitality. Challenges, however, including poverty, educational disparities, and restrictive policies, threaten their upward mobility. Policymakers who wish to harness Latino potential to ensure national prosperity and resilience should adopt policies that prioritize affordability, safety, and economic opportunity over ideological constraints.

Exodus: Affordability Crisis Sends Americans Packing From Big Cities

The first in a two-part series about the Great Dispersion of Americans across the country.

The AI Future: Between Certain Doom and Endless Prosperity

AI continues to become more complex and sophisticated, but public policy solutions do not.

The Castle, the Cathedral, and the College

Our civilization struggles to explain why anything should command allegiance beyond preference or power; its remnants echo a grandeur now distant.