Chernow Speaks of Twain But Doesn’t Know His Words

Mark Twain's greatness is not grasped by Ron Chernow's mammoth biography.

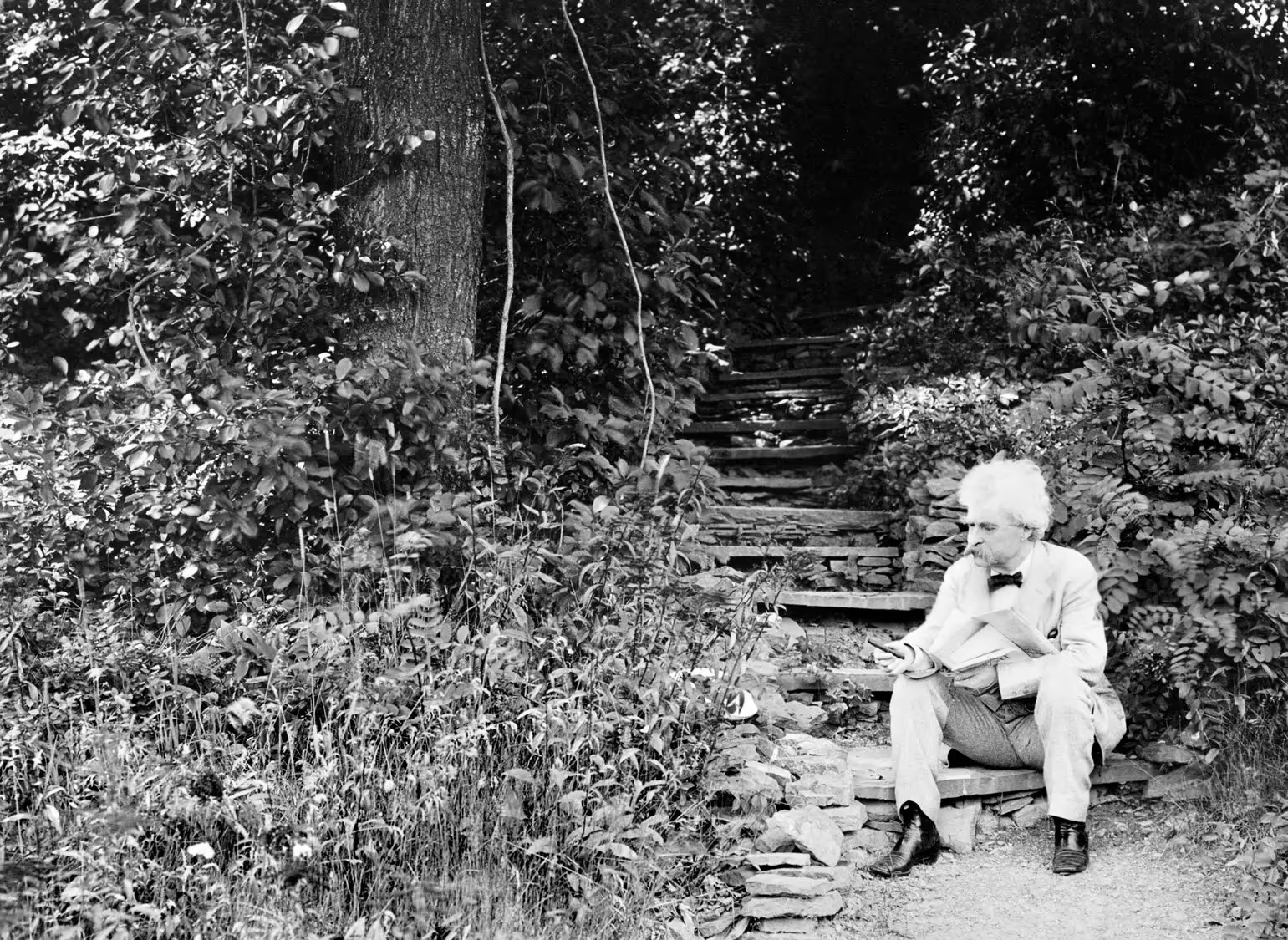

Horace—not Horace Greeley or Horace Grant but the Roman poet Horace—famously said that poetry should delight and instruct. If we apply this standard to Ron Chernow’s mammoth Mark Twain, I’ll grant it gets about half the job done, and that half almost entirely on the instruction side of the ledger. Samuel Langhorne Clemens (1835-1910) lived a fascinating life, rising from the muddy banks of the Mississippi River to storm the house of fame as Mark Twain, a pen name redolent of the great American river, its depths and shallows, and the steamboats navigating them. By the time of his death, Twain had rubbed elbows with every rank of American and European society. From his boyhood days, he loved a good yarn, and his powers of invention made him famous with the 1865 publication of “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.” The former printer’s devil from Hannibal, Missouri elevated his slow-boiling deadpan humor into an American art form, and the country reveled in his mirth. It’s hard to say what exactly tickles the funny bone about a man’s rigging a bet by filling a frog named Daniel Webster with quail shot, but evidently, it was something Americans could appreciate.

Chernow is a distinguished historian, not a man of letters, and he is not qualified to write on a great author like Mark Twain. Undoubtedly, Chernow is very gifted. His strengths are those of the duly honored bourgeois intellectual. His logical command of the facts, mastery of detail, and fluent prose are unassailable. And yet, because there is so very much of it, Chernow’s prose draws too much attention to itself.

Unlike the Paige typesetter on which Twain wasted a fortune, Chernow never breaks down. He is an astonishingly copious wordsmith, superbly gifted on his level, an immensely resourceful writer for whom the needed phrase is always at hand, and it is a pity he couldn’t recognize his limitations. After weeks of reading Mark Twain, one closes the cover on a book that is the sum of its parts and nothing more: a vast, flat, closely-knit aggregate of facts and commentary without the organic qualities denoted by such words as soul, unity, and form. It is a somber reminder that art has an elusive relationship with standard measures of intelligence.

Twain was a great man. To understand this quality, we can turn to his friend William James, who observes in his Psychology: The Briefer Course, “Our self-feeling depends entirely on what we back ourselves to be and do. It is determined by the ratio of our actualities to our supposed potentialities....” What James describes is a lot like betting on yourself. Twain bet on himself all the time. He often won his literary bets, rarely won his business bets, but this existential gambling paid off. His literary talents carried him into the first rank of American writers and made him one of the true shapers of the American psyche.

Because we do not live in an age of great men, Chernow brings Twain into our narrow contemporaneity by prescinding the great man from his greatness. Much of this tome is simply a running tally of Twain’s views of women, minorities, the South, white imperialism, and organized religion. Chernow loves to judge these things, to chew the common cud of our prize-winning intelligentsia, and he assumes he has the reader with him. Here are some characteristic utterances: “It is hard to think of another white author of his era who felt so warmly toward Blacks or cared more about their plight.” “It was an early sign of Twain’s future role as a doughty defender of women’s rights.” “To modern eyes, [Twain’s behavior] only reinforces the impression of an unhealthy interest in young girls.” The ubiquity of non-literary judgment—constant editorializing—seeps into the particles of Chernow’s prose: “With pardonable exaggeration, he said….” Chernow’s Twain is a celebrity activist. His biography marks the acceptance of Twain by the progressive establishment, and their Twain necessarily endorses their opinions—you might say Twain gives his life to endorse their opinions.

Where literature is concerned, Chernow is content to fly on autopilot. He is not an active agent of literary perception, seeking to compare and appreciate authors. He does not remark on the potent figure of Don Quixote standing behind Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. He jogs alongside Malory’s Morte D’Arthur, noting its relation to A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, but Malory’s work is badly summarized as a “lyrical fifteenth-century rendering of King Arthur.” Malory’s prose is ritualistic, ornamental, formulaic, syntactically various, orthographically fluid, ribbed with curious dialogue, and studded with polysyndeton. It has lyrical qualities, to be sure, but it is primarily the instrument of an epic romance. Chernow observes Twain’s attraction to Malory’s archaic language, but that’s as far as he goes. He does not compare and analyze their figures and idioms. He does not tell us why Twain loved Malory, or why Malory suited his purposes, or what Twain left out, or inverted, or exaggerated to transform Arthur’s England into Hank Morgan’s.

To a literary critic, the book is instructive without purpose, scholarly without perspective. Historical figures come and go, talking of Mark Twain: Bret Harte, Robert Louis Stevenson, Helen Keller, Winston Churchill, Ulysses S. Grant, John Hay, Woodrow Wilson, Nikola Tesla, Rudyard Kipling, Johann Straus, Henry James, Andrew Carnegie, Maxim Gorky, Martin Charcot, Richard von Krafft-Ebing. Yet literary history is left out. We encounter endless minor details about Twain’s wife and family, none of whom shared Twain’s literary greatness. Yet Twain’s literary heirs are barely considered. We meet with frequent reports of Twain’s carbuncles, gout, rheumatism, bronchitis, indigestion, lumbago, and toothache. Was he isolated in this respect, or have other authors suffered maladies and mined them for the gold of their art?

Beyond the disappointment in store for those anticipating a genuinely literary biography—something along the lines of Peter Ackroyd’s T. S. Eliot: A Life or A. N. Wilson’s C. S. Lewis: A Biography—there are literary facts to contend with. When his survey of Huck Finn’s socio-cultural impact reaches the year 2024 and Percival Everett’s “excellent, poignant retelling of Huck Finn titled James,” Chernow observes, “When talking to other Blacks, Jim switches to standard English, thus exposing the slave patter and pose of naivete as deliberate minstrel affectations adopted by the enslaved for self-preservation.” This is less interesting to me than is the fact that John Steinbeck, who wrote in the folksy tradition of Twain, appears to have invented the device in his 1952 novel East of Eden, with the Chinese-American character Lee (“Me talkee Chinese talk”) explaining his reliance on pidgin English to a white man: “It’s more than a convenience…It’s even more than self-protection. Mostly, we have to use it to be understood at all.” Of course, Everett had every right to adopt the device, but that is not my point.

The future of literature is in doubt. It is being dismembered and swallowed by politics. In happier times, students of literature could approach the topic through a variety of interweaving avenues, including the main lines of Western thought. Chernow, unfortunately, eschews intellectual history writ large. For instance, Twain was extremely guilt-ridden. His conscience tortured him, and he resembles no one more in this respect than Martin Luther, who insisted, “consciences are bound by the law of God alone.” Likewise, Twain clarified his Mugwump independence to a friend, “a man’s first duty is to his conscience.” Luther paid a high personal price for liberating the Christian conscience. To quote the intellectual historian Slavoj Žižek, he was “caught in a violent debilitating superego cycle: the more he acted, repented, punished, and tortured himself, did good deeds, and so on, the more he felt guilty.” Twain comments, “A conscience is like a child. If you pet it and play with it and let it have everything that it wants, it becomes spoiled and intrudes on all your amusements and most of your griefs.” The comparison opens fertile territory for understanding Mark Twain’s writings, as does his relation to the Enlightenment, though I cannot recall Chernow once using the word in its capital “E” sense. Particularly interesting is how the Rousseauan note inflects Twain’s satirical angle: “All have entered [the world] naked, unashamed, and clean in mind.” Such intellectual landmarks offer perspective and supply relief from the pullulation of grubby details.

The young writer whose powers are fertilized by Mark Twain is a different matter: personality and the unconscious come directly into play. In this respect, what doesn’t count at all is the editorializing Chernow practices. Late in his life, Twain wrote his daughter Clara, applauding her musical pursuits: “It is as I used to be with the pen, long ago, & it is life, LIFE, LIFE!—there is no life comparable to it for a moment. Genius lives in a world of its own.” Genius attracts genius in a rarefied atmosphere that excludes political chatter. Editorializing is no more at home there than on the surface of the sun.

Lee Oser’s most recent album with The Riflebirds of Portland is Windmills on the Moon. His most recent scholarly book is Christian Humanism in Shakespeare: A Study in Religion and Literature. His most recent novel is Old Enemies: A Satire. A former president of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers (ALSCW), he teaches at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Pursuit of Happiness

The Rise of Latino America

In The Rise of Latino America, Hernandez & Kotkin argue that Latinos, who are projected to become America’s largest ethnic group, are a dynamic force shaping the nation’s demographic, economic, and cultural future. Far from being a marginalized group defined by oppression, Latinos are integral to America’s story. They drive economic growth, cultural evolution, and workforce vitality. Challenges, however, including poverty, educational disparities, and restrictive policies, threaten their upward mobility. Policymakers who wish to harness Latino potential to ensure national prosperity and resilience should adopt policies that prioritize affordability, safety, and economic opportunity over ideological constraints.

Exodus: Affordability Crisis Sends Americans Packing From Big Cities

The first in a two-part series about the Great Dispersion of Americans across the country.

One Nation Spaced Out

Kevin Sabet’s new book addresses a problem that has bedeviled us for thousands of years: What should individuals and society do about the use of psychoactive substances?

The AI Frontier Must be Fiercely Competitive

In the long run, overregulation could run the risk of making AI less safe.