Carl Schmitt: A Window into the Postliberal Id

Schmitt’s friend–enemy politics may appeal to postliberal admirers of conflict and hierarchy, but real political meaning lies not in tribal enmity but in civic friendship ordered to the common good.

Adrian Vermeule says that a sign of superficiality in commentary on Carl Schmitt is that the commentator cites only The Concept of the Political and Political Theology, works that Vermeule thinks were not even Schmitt’s most interesting. Well, I have now written two essays critiquing those specific works of Schmitt and, risking Vermeule's criticism, I will not bother critiquing any other of Schmitt’s works. Why? Because almost nobody reads them. As I argue in those two essays, The Concept of the Political and Political Theology are Schmitt’s most popular works precisely because they help people rationalize tribalist and authoritarian politics.

Vermeule may downplay those two works, but they have influenced his thinking. It was, after all, in the years following 9/11 and during the federal government’s “war on terror” that Vermeule first engaged with Schmitt, especially on emergency powers, executive discretion, and “states of exception.” His interest in Schmitt didn’t fade after he converted to Catholicism and, along with Patrick Deneen, became a leading figure in the Catholic postliberal movement. In Common Good Constitutionalism, Vermeule even interprets the principle of subsidiarity through the lens of states of exception. Still, he remains one of the few postliberals openly supportive of Carl Schmitt. The Nazi association was probably too much for most others.

But that does not mean that Schmitt’s thought is irrelevant to the rest of Vermeule’s postliberal clique. It is noteworthy that in an interview with Bishop Robert Barron, Patrick Deneen lists Louis Bonald and Juan Donoso Cortés as nineteenth-century authors who were proven correct in their criticisms of liberalism. Those are two of the three reactionary thinkers that Schmitt held up as his forerunners in Political Theology (though not without some constructive criticism). Those were precisely the three reactionary thinkers that Schmitt held up as his forerunners in Political Theology (though not without some constructive criticism). Therefore, even when postliberals do not cite Schmitt explicitly, his influence is clearly present, usually indirectly through their associate Vermeule.

But what interests me more is how Schmitt illuminates what underlies postliberals' arguments: the implicit values they endorse and the motives that drive their always-shifting project. Responding to their explicit ideas, I have had to respond to Thomas Pink’s well-intentioned and thoughtful, though I think misguided, integralist interpretation of the Second Vatican Council’s Declaration on Religious Freedom, Dignitatis Humanae. Pink is not part of their group, but at one point they found his work pivotal to their project. I have also had to research and respond to Patrick Deneen’s critique of American liberal democracy and Vermeule’s critique of Madisonian constitutionalism. That was all fruitful, too, but what I discovered in the process was how flexible the American Catholic postliberals were at adapting to new political realities—integralism became passé (and unworkable), America became acceptable (although requiring reinterpretation), immigration, once considered beneficial when it is the immigration of Catholics, is now to be severely restricted, and so on.

It was in understanding the rationale behind Schmitt’s emphasis on a friend-enemy distinction in politics and the justification for his defense of personal sovereignty (as revealed in states of exception) that I came to appreciate better what drives postliberals, even those who do not explicitly endorse Carl Schmitt. Bringing these implicit values to light can help critique them from a Christian perspective.

The Princeps as Vicar of Christ – A “Transcendent” Sovereign

One common thread of the political vision of postliberals is an attraction to autocrats. They might say this is grounded in concern for the common good, but that only gets them so far. Among them, Adrian Vermeule has the most sophisticated understanding of a Catholic view of the common good. Drawing on the Reason of State tradition, Vermeule prefers to discuss the common good in terms of three overarching goods that are common to members of a political community: peace, justice, and abundance. This is legitimate. One can also break it down in material, rather than formal, terms — that is, by discussing material conditions that promote those formal values (e.g., that the common good requires a functioning legal system). Vermeule’s abstract discussion of the common good is unobjectionable.

And yet, there is little effort on the part of postliberals to consider the empirical case for modern constitutional democracy insofar as it promotes those common goods. If it was only those common goods that concerned them, they would find this a problem for their defense of more autocratic regimes. For instance, liberal democratic countries almost always outpace autocratic countries in wealth, peace, and resistance to corruption. Vermeule is the one who has made the most serious effort to defend his preferred institutional arrangements, but at best, he is left to claim that America’s success happened despite its Madisonian constitution, or that it is not really all that Madisonian because it evolved away from it. With the former argument, he massively underrates the value of a free civil society, which the Madisonian constitution secures at the cost of less bureaucratic micromanagement. As regards the latter argument, it is difficult to take seriously because Vermeule is always looking for ways to weaken the same separation of powers and checks & balances that he says were already abandoned.

If you bring up the issue of the empirical success of liberal democracies, they will likely dismiss such claims with slogans: “we care about more than just GDP…” Okay, well, GDP is a valuable indicator of a country's wealth. It is a good proxy for how much less labor it takes, whether unskilled or skilled, to acquire the goods most people want and need. Meanwhile, those postliberals, less sophisticated than Vermeule, bypass the issue by often using the common good as a slogan, presuming that, per se, it implies a need for statist and autocratic measures, ignoring the fact that people can disagree about the state’s role and competency for securing all elements of the common good.

Schmitt helps us to see what these postliberals are after. For Schmitt, what makes autocratic (usually still democratic) rule enticing is its element of transcendence. “Sovereign is he who makes the exception,” the first words of his Political Theology. Implicit in Schmitt’s account is that a sovereign individual who, so to speak, transcends the political community, who can act above the law, and who is legitimated merely by his (or her) capacity to protect the community, mirrors the relationship between God and His people. In Schmitt’s view, a deist worldview desacralized politics and gave us a rule not of a personal sovereign but of impersonal law, legitimized by the community itself. I would posit that for many of these postliberals, it is a political sovereign, acting as a kind of vicar of Christ (analogous to the pope), that attracts them toward postliberalism, and this more so than any common goods that they think this arrangement would better secure (which it will not).

Unfortunately, the intellectual history Schmitt uses to link personal sovereignty with traditional Catholicism is shallow and questionable. It was not deism that desacralized politics so much as Christianity itself; it did this by recognizing a dualism between God’s kingdom and the earthly realm, what Augustine called the “City of God” and the “City of Man”—foreshadowed by the Stoic belief in two commonwealths, the civic polity and the broader world. Schmitt’s model, however, aligns more with that of the son of “god” (i.e., Caesar, what Augustus called himself) than with the Son of God, Jesus, whose kingdom, unlike Augustus's, “is not of this world.”

When medieval Christians rediscovered Roman Law, it was a valuable acquisition. However, the Roman Law they recovered still implied the autocratic assumptions of imperial Rome (e.g., whatever pleases the princeps has the force of law; the princeps is absolved from the law). This had a limited effect on Medieval Europe until the rise of large, modern, bureaucratic territorial states starting in the 1400s. Then the autocratic elements of the Roman Law were abused by powerful princes. In the Catholic kingdoms, this autocratic rule did not create an integralist system that presupposed the subordination of the temporal power to the spiritual authority of the Church, but rather something closer to Gallicanism, with temporal princes using the Church for their own ends. Louis XIV, for example, was closer to Philip the Fair than Louis IX. Schmitt inherits from the nineteenth-century Catholic reactionary tradition a romanticized view of these baroque Catholic “sovereigns,” who created a lot of trouble for orthodox Catholics; and scholastics like Juan de Mariana severely criticized their absolutist rule, without yet knowing an institutional alternative.

For whatever reason, Vermeule and Deneen’s group of postliberals appears to share Schmitt’s desire for some kind of transcendent sovereign. Regardless of one’s opinion on that, it is not particularly Christian; it’s more an inheritance of Caesar than Christ, more Rome than Jerusalem.

A Return to Tribal Politics

As I have argued elsewhere, the practical use of Schmitt’s friend-enemy distinction from his essay The Concept of the Political is almost always to rationalize tribalist politics, and that is even its function in Schmitt’s essay. He does not argue that liberal-democratic politics, which tries to limit conflict, is impossible. He thinks it will have a tough time defending itself against internal and external foes (a doubtful empirical claim). But even if it were to succeed, Schmitt would still oppose it, because its success would make politics less meaningful. Those who share his inclination for tribalist politics, perhaps also implicit in his desire to be subject to a personal sovereign, find this compelling. The rest of us do not. Whether politics always involves distinguishing friends from enemies, or whether the state needs to make such distinctions, is not the point. From a normative perspective, these distinctions are derivative. What matters is the political community itself, whose well-being, judged by the fulfillment of its common good, is a form of civic friendship among its members. However, it is not my aim here to critique Schmitt again.

What interests me is how this same type of tribalist politics motivates the above-mentioned group of American Catholic postliberals (e.g., Vermeule, Deneen, Vice President J.D. Vance, Kevin Roberts, etc.). Despite all his shots at classically liberal, Reaganite, what he calls right-liberal, conservatives over the last few years, Vermeule responded to the recent fight about Kevin Roberts’s support for Tucker Carlson by criticizing the infighting as weakening the right in its fight against the enemy (presumably the left). Similarly, J.D. Vance called for an end to infighting, telling people on the right to focus instead on their enemy, the “radical leftist movement” that killed his friend Charlie Kirk — an odd claim because only one person killed Charlie Kirk. It is precisely this tribalism that explains their flexibility as regards policy: they desire to be united with friends against enemies under a “sovereign” (presumably Trump and, later, Vance), with this fight providing meaning, a sense of community, and transcendence. Whether that community and its transcendence are a Christian sort is a separate matter.

The silence of these postliberals in response to Vance’s indifference about the fate of Ukraine, Tucker Carlson’s explicit support for Putin, and Viktor Orban’s excuses for Putin, as well as their silence or even support for the administration’s sometimes inhumane immigration enforcement — despite opposition from two popes and myriad bishops—gives the impression that it is not a properly Catholic politics at all. What distinguishes these postliberals most from the disciples of Nick Fuentes (Groypers), besides their lack of racism or antisemitism, is that postliberals see scapegoating as potentially useful for uniting people in a common fight under a strong man — consider J.D. Vance’s scapegoating of Haitian immigrants in Springfield, OH. Groypers, by contrast, are motivated first and foremost by their resentment of those same scapegoats (e.g., Jews, immigrants), which is what leads them into tribal politics. Jason Hart has recorded numerous examples of postliberal groups hiring young right-wing, Groyper-sympathetic radicals to fill DC positions as loyalists. Postliberal Rod Dreher has even acknowledged this problem. That is not all that surprising. Postliberals and Groypers are two sides of the same coin: an aristocratic class of demagogues and a faction of resentful plebs who are inclined to go along, each carrying the papal flag despite their alienation from the politics of the actual pope.

Thomas Howes has a PhD in Philosophy from the Catholic University in America and is a member of the James Madison Society at Princeton.

Politics

National Civitas Institute Poll: Americans are Anxious and Frustrated, Creating a Challenging Environment for Leaders

The poll reveals a deeply pessimistic American electorate, with a majority convinced the nation is on the wrong track.

.webp)

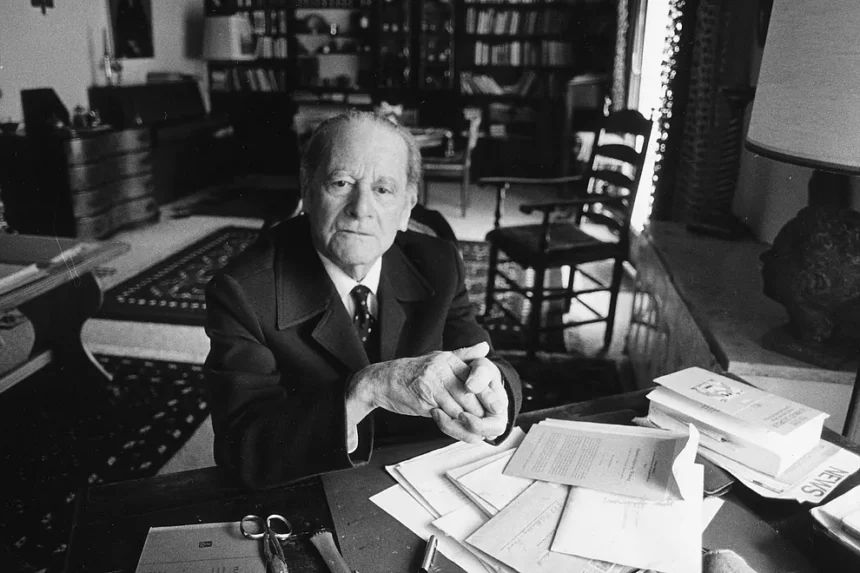

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

This article explores Leo Strauss’s thoughts on Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1954 “Natural Right” course transcript.

%20(1).avif)

Long Distance Migration as a Two-Step Sorting Process: The Resettlement of Californians in Texas

Here we press the question of whether the well-documented stream of migrants relocating from California to Texas has been sufficient to alter the political complexion of the destination state.

%20(3).avif)

Who's That Knocking? A Study of the Strategic Choices Facing Large-Scale Grassroots Canvassing Efforts

Although there is a consensus that personalized forms of campaign outreach are more likely to be effective at either mobilizing or even persuading voters, there remains uncertainty about how campaigns should implement get-out-the-vote (GOTV) programs, especially at a truly expansive scale.

California’s Green Policies Destroy Blue-Collar Jobs

The problem here lies not with racism, or lack of reparations, as Newsom and “progressives” insist, but with their own policies, which devastate minority communities.

There's a Perception Gap With the U.S. Economy

As we approach another election cycle, it’s worth asking: what’s real, what’s political theater, and what does it all mean if Democrats regain control of the House?

.jpg)

Confusion about Commandeering

State governments are not instrumentalities or vassals of the federal government but rather sovereign entities with their own legal authority.

A Climate Science Manual for Judges Discredits Itself

All is not well with the Reference Manual for Scientific Evidence. This is a loss for the public trust of science.

.avif)