The Moral Case for America in a Nutshell

Cooperation is how societies become truly richer, and the richer a society is, the more resources citizens have to pay for public goods and private charity.

Anti-Americanism is hardly new. But why is it now so widespread and vitriolic, especially among young adults? We must recognize that America’s detractors have been making a simple and effective moral case against America for some time now, and it’s bearing ever more fruit. America’s proponents now have no choice but to articulate their own simple and effective moral case for our way of life.

The Moral Case Against America

Before the fall of the Soviet Union, the primary argument against America was based on Marxist materialism. In short, capitalist economies like ours fail to make optimal use of resources to serve the common good. Too much goes to owners of capital, while too little goes to labor. Marx predicted that disaffected masses would eventually force the adoption of increasingly socialist systems to increase the share of income going to labor, ultimately culminating in communism.

What proponents of America have failed to recognize is that America’s detractors have largely abandoned this argument. Improving conditions, even among the poorest people in formerly communist nations, led to it falling on deaf ears. In a 2019 Pew Research Center Study, survey results showed widespread belief among those living in formerly communist countries that life satisfaction had improved dramatically over the last 30 years.

In short, detractors switched gears. They began making a direct moral case against America, one that did not depend on Marxist materialism or class warfare.

They now argue that even if America provides ample material resources for everyone, it is nevertheless immoral. This is because it was built on an immoral foundation (slavery – the epitome of oppression) and it still operates in an immoral way (ongoing oppression through systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, etc.).

Oppression was a central component of traditional Marxism as an explanation of the drivers of growing class division. But today’s detractors now focus on the immorality of oppression per se. This approach has the advantage of not requiring the endorsement of any particular conception of utopia or view of how history will unfold. It only requires the belief that rectifying past and combating present oppression is morally necessary. Who can disagree with that?

This switch in rhetorical strategy has been working exceedingly well. But that should not be surprising. In matters of debate, morality trumps everything.

The Oppression Thesis

The crux of the moral case against America is therefore derived from what we might call the oppression thesis. It contends that the rise of the West and America is largely the story of the strong getting ever better at oppressing the weak. America is, therefore, immoral because oppressing people is immoral.

Virtually all anti-Americanism today comports with the oppression thesis. It is simple yet capacious and harmonious at the same time. Because of this, it possesses a rhetorical elegance that is especially appealing to young minds.

The division between the oppressed and the oppressors aligns with the “us” versus “them” mentality of tribal thinking. Since our genes predispose us to think in tribal terms, the oppression thesis seems plausible on its face.

The good news is that oppressors and the innocents who benefit from past oppression can atone and virtue signal simultaneously by proclaiming their support for redistributive justice. Many who should know better cannot resist the temptation to obtain social approval by joining in. As more join in, those left on the sideline look ever more callous and self-deluded. This induces even more to jump in, making the oppression thesis seem ever more like common sense over time.

Detractors of the West and America are right to call attention to oppression, of course. Oppression is an important part of the story of the West and America. But it cannot possibly explain the rise of the West and America.

No one disputes that the poor live better today than ever before in almost every corner of the world. But the real incomes of the rich cannot rise over centuries by the rich simply stealing ever more from the poor.

One might argue that the oppression thesis has not gone unchallenged since there are many cogent explanations for why America is moral. But none of these attempts provides a simple yet capacious and harmonizing idea that can go toe-to-toe with the oppression thesis.

The Moral Case For America

The moral case for America is rooted in the concept of cooperation. In his book, The Righteous Mind (2012), Jonathan Haidt famously stated: “The most powerful force ever known on this planet is human cooperation – a force for construction and destruction.” He’s right, and the moral case for America begins with seeing why.

We cooperate by working with others because doing so yields a value greater than the sum of the parts. Suppose that alone I make 10 of something, alone you make 10, but working together we make 26. The additional 6 units are a kind of surplus – a cooperative surplus – and it’s what induces us to freely choose to cooperate because it makes it possible for both of us to end up with more at the same time.

The easiest way to illustrate cooperation in concrete terms is with a simple example from long ago: two cousins, say, spearfishing from the edge of a river, about 25 yards apart.

Alone, each normally spears about 10 fish per afternoon. Suppose the upstream cousin’s spear skips across the surface and starts heading downstream. Wading in to recover it, he ends up walking downstream to catch up to it.

The other cousin is now spearing fish more rapidly than ever before. Later, they conjecture that the upstream cousin was effectively herding the fish past the downstream cousin at a much faster rate than normal. The next day, they tried having one herd while the other speared. They found that, together, they speared 26 fish, 6 more than the 20 they speared when not cooperating. Each can now take home 13 rather than 10 fish. Alternatively, each can reduce the time spent spearing fish. Either way, cooperation produced a significant benefit for everyone involved without harming anyone.

Whether it’s spearing fish, moving sleeper sofas, or making birdhouses together, the salient property is the same: the value of the whole exceeds the sum of the values of the parts.

This is why cooperation is the first step to increasing output per capita and therefore achieving mass flourishing. Incredibly, we will see below why two other obvious contributors to mass flourishing – freedom and trust – almost certainly coevolved with cooperation.

The Cooperation Thesis

The crux of the moral case for America is derived from what we might call the cooperation thesis. It contends that the rise of the West and America is largely the story of people getting ever better at cooperating in ever larger contexts. America’s free market democracy and constitutional republic are the most effective systems of cooperation ever to exist. America is therefore an exceptionally moral country because, as we will see below, cooperation between ethical guardrails is inherently moral.

What makes America so good at cooperation? While all humans are good at cooperating in small group contexts, as they evolved in, few countries can pull off large group cooperation.

This is a big problem because Adam Smith was right.

Cooperating by dividing tasks to unleash the power of specialization is the key to producing more per person. Smith’s famous pin factory example, based on actual data, revealed a 23,900% increase in productivity achieved by producing pins through cooperation, specifically through an organized division of labor. Some have suggested that he overstated the effect, but even if he were off by an order of magnitude that would still be 2,390%. To put that in context, if you are of roughly normal height and it went up 100%, you’d be the tallest human to ever live.

Smith then explained why this effect increases dramatically as the number of people over whom to divide tasks is increased. It follows that to get the most out of cooperation, we need to be able to collaborate in large groups. This benefit of scale is the crux of his argument for free trade.

Our capacity to cooperate effectively in large groups depends on our trust in strangers and in the system. Our genes have no reason to equip us for this because, until very recently, we lived exclusively in small groups. But then our extraordinary capacity for language allowed some groups to develop cultural and institutional work arounds that increased the size of groups within which cooperation could be undertaken. The societies that did this best became more productive and pulled ahead.

America’s Story of Cooperation

In the early colonial period, American culture and institutions co-evolved to produce two things that turned out to be mighty catalysts for cooperation: freedom and trust.

Americans are often accused of taking freedom for granted, while few appreciate how important trust is to our way of life. The complex relationship among freedom, trust, and cooperation makes it difficult for Americans to appreciate how much cooperation occurs around them every day. For Americans, cooperation is like water to fish. And fish are, of course, the last to discover water.

Freedom

In the early colonial period, most Americans were very lightly governed from abroad.

This led the earliest Americans to learn how to govern themselves in a highly cooperative fashion. There was a king and a colonial governor, but most government occurred at the townhall level, far from the heavy hand of formal government power.

Being lightly governed also led them to think, speak, and act as they saw fit, provided it didn’t impinge on the rights of others.

Such freedom made cooperation a more effective means of advancing the common good. Free-thinking cooperators will normally choose what’s best for themselves. But this turns out to be what’s also best for society because they will choose modes of cooperation and/or cooperative partners that maximize the cooperative surplus.

Suppose that alone you make 10 and Bob makes 10, and together you make 26. Suppose that alone you make 10 and Sue makes 10, but together you make 30. If you are free, you will choose to cooperate with Sue because it will likely yield the greatest benefit to you. But that amounts to choosing what is, by definition, the most effective partner for cooperation, producing the most value for society per capita.

Under freedom, if there is a social convention of splitting the surplus equally, then maximizing the size of the surplus becomes the only way to increase one’s own payoff.

But what if Sue demands an unequal split of the surplus?

Free people search among potential cooperative partners for the best terms. If there are others just like Sue, except that they offer something closer to an equal split of the surplus, you will choose one of them instead. Over time competition among potential cooperative partners drives everyone to choose partners who will not demand more than an equal split of the surplus. Fear of being excluded induces others to propose an equal split from the outset.

Contrast this with coerced cooperation. In such cases cooperation will be directed toward maximizing the payoff of the coercer even if that makes everyone else worse off. There is simply no need for the coercer to share the cooperative surplus or to even cover the opportunity cost of the coerced, since the coerced aren’t free to opt out.

Cooperation in America did not require anyone to be in charge of society to direct what would be produced through cooperation, who would cooperate with whom, or what the terms would be. Thus, the realization of general prosperity obviously did not depend on the wisdom of a central planning committee or a brilliant leader. This generated skepticism about promises to improve society by trading a small degree of liberty for greater security.

Trust

A culture of freedom also helped cultivate a high trust society. In Europe, peasants had to cooperate with others on the same estate whether they wanted to or not. But American parents knew that their children’s contemporaries would be free to avoid cooperating with them if they couldn’t trust them, thereby cutting them off from the benefits of cooperation.

Parents, therefore, worried as much about making their children trustworthy as they did teaching them practical skills. This fostered a strong norm of trustworthiness, making it rational for citizens to trust one another. And since those in early American government were drawn from a sample of highly trustworthy people, there was a good deal of trust in the system.

With rare exception, citizens could trust those in power to fairly enforce contracts and property rights, and to abide by the rule of law. This increased the expected returns to cooperation by ensuring that citizens could keep what they had earned.

It follows that societies that raise their children to be honest will be wealthier than those that do not, because greater cooperative surpluses can accumulate. And because Adam Smith was right about the power of large scale cooperation, societies, like America, that raise their children to be honest even with strangers will do best of all.

The Morality of Cooperation

Cooperation involves behavior that is consistent with everyone respecting everyone else’s freedom. Failing to respect others’ freedom, dignity, and trust risks their choosing to avoid you in the future. Moreover, in a society in which culture and institutions have long fostered extensive cooperative activity, people become accustomed to solving their problems without always enlisting governmental power.

Cooperation also requires and cultivates prosocial behavior. Try to think of a behavior or trait that you would regard as pro-social that wouldn’t also make someone a desirable transaction partner. Families that want their children to benefit from being viewed as good potential cooperators, therefore, have a strong incentive to raise their children to possess character traits that produce such morally laudable behavior robustly through habituation.

When we cooperate honestly, we create more output per capita while respecting the rights of others (otherwise, they will choose not to cooperate with us in the future). Echoing Kant’s categorical imperative, this means we only use each other as means to ends by mutual consent. This is how communities build themselves in Tocquevillian fashion. It is how we create an “us” that is infinitely more meaningful than tribal identity. This is the story of the rise of America.

Finally, Americans are the most generous people in the world. While this is no doubt influenced by our generosity of spirit, such generosity would be moot in the absence of sufficient resources. Cooperation is how societies become truly richer, and the richer a society is, the more resources citizens have to pay for public goods and private charity.

The More Moral Case for America in a Nutshell

1. Ever more effective cooperation, not ever more effective oppression, is what drove the evolution of Western and American culture and institutions to support ever more effective cooperation even in large group contexts.

2. Cooperation depends upon, and cultivates, both freedom and trust. It is what ultimately makes general prosperity possible. These are three of the most important pillars to mass human flourishing.

3. Cooperation, when conducted within obvious ethical guardrails, produces positive moral outcomes for the individuals directly involved and for society as a whole. American culture and institutions are exceptionally good at fostering cooperation. So America is, therefore, exceptionally moral.

David C. Rose is co-founder and CEO of The American Civics Academy, Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, and author of The Moral Foundation of Economic Behavior and Why Culture Matters Most, both from Oxford University Press.

Pursuit of Happiness

The Rise of Latino America

In The Rise of Latino America, Hernandez & Kotkin argue that Latinos, who are projected to become America’s largest ethnic group, are a dynamic force shaping the nation’s demographic, economic, and cultural future. Far from being a marginalized group defined by oppression, Latinos are integral to America’s story. They drive economic growth, cultural evolution, and workforce vitality. Challenges, however, including poverty, educational disparities, and restrictive policies, threaten their upward mobility. Policymakers who wish to harness Latino potential to ensure national prosperity and resilience should adopt policies that prioritize affordability, safety, and economic opportunity over ideological constraints.

Exodus: Affordability Crisis Sends Americans Packing From Big Cities

The first in a two-part series about the Great Dispersion of Americans across the country.

.jpg)

The False Equivalence of Multicultural Day

Parents have an affirmative obligation to reinforce patriotic values and counter the narratives that are taught in school.

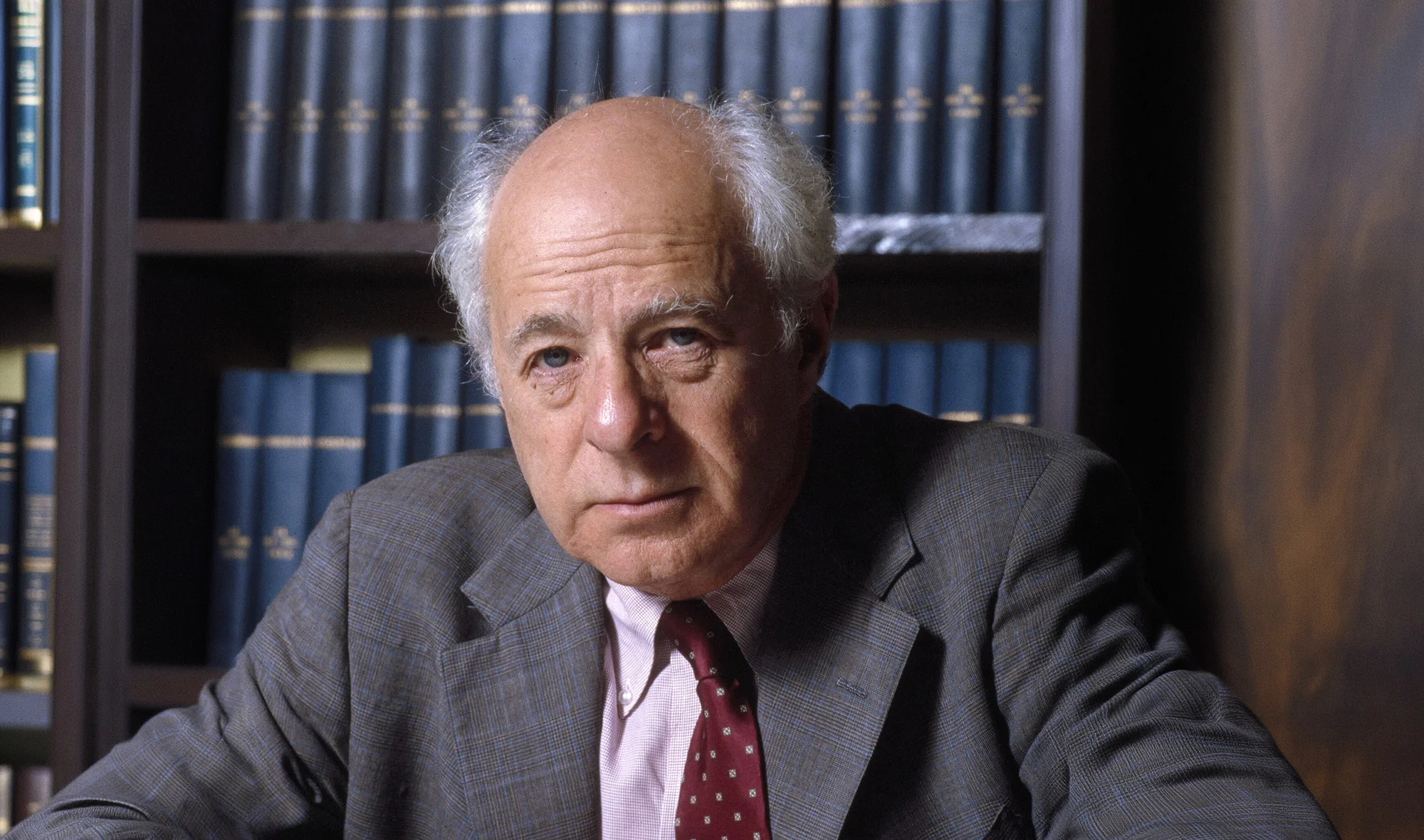

Norman Podhoretz: American Patriot, Faithful Jew, and Indomitable Defender of Civilization

Podhoretz never turned on the promise of America.