Countering the Present Disorder

Civilization has always been fragile. Is this time different?

Civilization appears fragile.

Raging wars, faltering economies, and fragmenting societies fuel the perception. Israel’s June 13 Operation Rising Lion, attacking the Islamic Republic of Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missiles programs, and the United States’ June 22 Operation Midnight Hammer, dealing devasting blows to Iranian nuclear facilities at Natanz, Fordow, and Isfahan, are the latest battles in the long-standing war that Tehran’s theocrats have been waging against Israel, America, and the West. Russia’s protracted war of conquest against Ukraine has destabilized Europe and strained relations among NATO countries. The wars in the Middle East and Europe complicate the great-power-competition calculations – not least surrounding the future of Taiwan – of the United States and the Chinese Communist Party. Tensions between nuclear-armed Pakistan and nuclear-armed India may reignite at any moment. Meanwhile, terrorists enjoy growing access to increasingly affordable weapons of mass destruction – nuclear, biological, chemical, and cyber. War and the accompanying supply chain disruptions endanger the global economy. Growing debt burdens both rich and poor countries. Meanwhile, in the West’s liberal democracies, distrust and resentment roil relations between highly credentialed managerial elites and middle- and working-class men and women, eroding citizens’ sense that they are engaged in a common civic enterprise.

Then again, civilization has always been fragile. Natural disasters and human error, weakness, and turpitude have constantly imperiled the moral and political order that human beings manage to impose on themselves, and their families, communities, and nations. The threat of violent death at the hands of other human beings – from intra-family and intra-tribe enmities to wars among peoples and nations – has marked human civilization from time immemorial. And until the rise of capitalism, scarcity and material want belonged to the common condition of humanity.

Moreover, enabled in no small part by revolutions in industrialization, communications, and transportation, the last century featured three globe-spanning conflicts and an economic crisis that put civilizations to a severe test. World War I, resulting from a tinder box of European interests and alliances, brought about the deaths of more than 15 million people. The Great Depression inflicted massive hardship not only on the United States but also, because of the interconnectedness of countries’ economies, on peoples and nations around the globe. World War II, undertaken by Hitler and the Nazis with the subsidiary aim of exterminating the Jewish people and the ultimate aim of subjecting the world to German rule, caused the deaths of approximately 60 million people. In their efforts in the 20th century to spread and enforce the doctrines of Karl Marx, the Soviet Union, the Chinese Communist Party, and fellow communists killed almost 100 million people. And fueled by the Soviet Union’s military conquest of Eastern Europe and Moscow’s quest for global hegemony, the Cold War drove the world to the brink of nuclear conflagration, most dramatically but not only in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Despite the evidence that civilization has always been hard won and easily lost, Robert Kaplan worries that this time is different. In Waste Land: A World in Permanent Crisis, the prolific author of bestselling books and influential long-form journalism advances a dire diagnosis of twenty-first century geopolitics through a characteristically eclectic blend of geography, demography, and history; diplomacy and military affairs; and culture, literature, and philosophy. Kaplan argues that as technology makes our world smaller and more connected, geopolitics grows more unpredictable, tumultuous, and authoritarian. The simultaneous decline of three great powers – Russia, China, and the United States – heightens the instability of the emerging “global civilization.” But “the primary change in geopolitics,” according to Kaplan, stems from “urbanization, and the intensification of politics that it leads to.”

Neither left nor right, in his view, provides adequate answers to what Kaplan characterizes as the “permanent crisis” engulfing the world. Instead, he believes that reviving dedication to individual freedom, human equality, toleration of competing beliefs and opinions, respect for the rule of law, and the virtue of political moderation – the backbone of the American experiment in ordered liberty – will maximize our prospects of warding off the mounting threat of carnage and chaos.

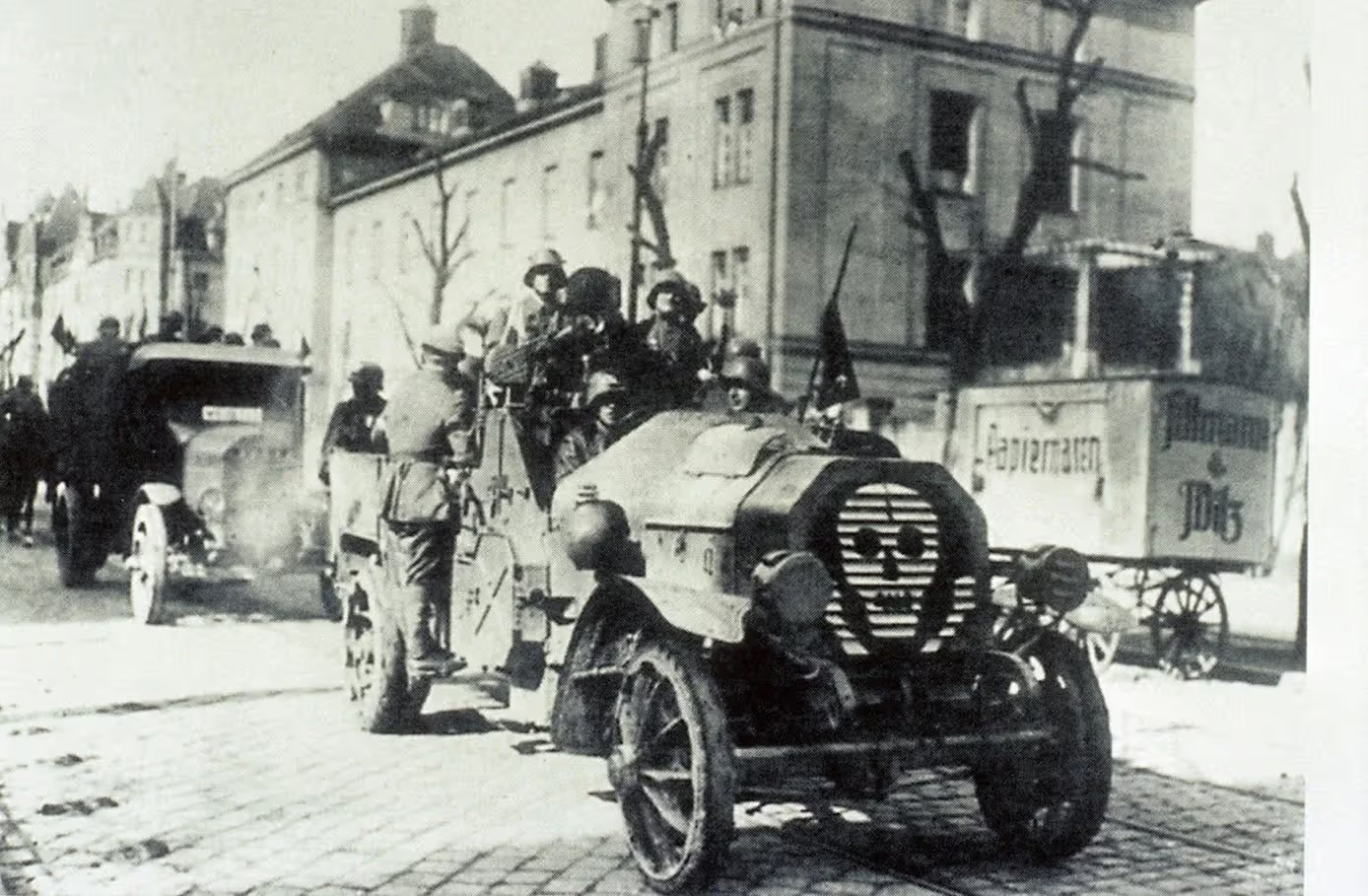

Kaplan compares “our global crisis” to the condition of short-lived Weimar Germany, “a candy-coated horror tale: a cradle of modernity that gave birth to fascism and totalitarianism.” Established by Germany in 1918 following its loss in World War I, the Weimar Republic collapsed into National Socialism in 1933. Weimar “was less a government,” writes Kaplan, “than a system of belligerent and far-flung competing parts, given the regional differences of a sprawling and, in historical terms, recently united Germany.” Something similar, he maintains, can be said about “our world today, with its great cultural and even civilizational differences, yet on another level becoming increasingly united at the same time.” As in Weimar, mounting crises afflict an ever more interconnected world – “whether it be Covid-19, a global recession, great-power conflicts, or unprecedented climate change” – even as peoples and nations lack the means for addressing collectively the shared crises.

Although he describes a grim world, Kaplan rejects fatalism. “The key is to make constructive use of our fears about Weimar, so as to be wary about the future without giving into fate.” History is a blend of “large, overwhelming forces of geography, culture, and economics” and “contingencies based on pivotal personalities.” Preserving civilization and heading off disarray depend on understanding these forces and personalities. While Kaplan can “see no Hitler in our midst, or even a totalitarian world state,” this hardly alleviates his anxieties since there is little reason to assume “that the next phase of history will provide any relief to the present one.”

The simultaneous decline of the world’s three most powerful nation-states, argues Kaplan, deserves our immediate attention.

Since its czarist days, Russia has been “Europe’s principal dilemma.” Rather than resolve the dilemma, the Soviet Union’s disbandment in 1991 gave it a new form by releasing traditional Russian nationalism and authoritarianism from their Marxist-Leninist trappings. Russia’s brutal war of conquest against Ukraine shows, argues Kaplan, that there “is certainly not a world governed by a rules-based order as polite gatherings of the global elite like to define it, but rather a world of broad, overlapping areas of tension, raw intimidation, and military standoffs.” At the same time, “the war, in which a country of 44 million people has had at times the military advantage over a nuclear power of 143 million, has exposed the Russian Empire as the sick man of Eurasia, just as the Ottoman Empire was for decades the sick man of Europe before it collapsed in World War I.”

China’s decline follows a breathtakingly rapid ascent after the death of Mao Zedong. “No nation in recorded economic history has improved the standard of living and the quality of life of so many people as quickly as China has under the extraordinary rule of Deng Xiaoping and his immediate successors,” writes Kaplan. “Deng’s crucial decision, which has determined his status as a great historical figure, was his introduction of elements of capitalism into Communist China gradually, rather than through shock therapy as the Russians under American guidance attempted.” However, “[General Secretary] Xi Jinping has returned China to the die-hard authoritarianism, bordering on totalitarianism, associated with Mao.” Rather than offer remedies, Xi’s authoritarian rule appears to have exacerbated the deleterious effects of China’s slowing growth, aging population, shrinking work force, and rising social and political tensions.

While the United States remains a “powerful behemoth,” Kaplan identifies two components of American decline, which he regards as the most consequential instance of the decline of the West. The quality of American leadership, he contends, has deteriorated dramatically since George H.W. Bush, the last of the Cold War presidents, left the White House in 1993. Meanwhile, social, political, and cultural animosities have ravaged self-government in America. Their scorn for the other side leaves left and right unable to cooperate in ameliorating the economic inequities of globalization, the explosion of national debt, the lawlessness of open borders, the politicization of the educational system, the pollution of the environment, and the breakdown of social cohesion.

As Russia, China, and the United States develop increasingly destructive weapons while managing their affairs with ever greater ineptitude, worldwide urbanization spurs its own distinctive pathologies. “Over 55% of humanity lives in cities, by 2050 over two-thirds of humanity will be urban, and increasingly densely urban,” reports Kaplan. Cities serve elites, he argues, while amplifying their estrangement from ordinary people and ordinary people’s estrangement from them. The resulting domestic instability destabilizes international affairs.

The destabilizing effects of urban life are especially apparent in the United States, approximately 85 percent of whose population lives in greater metropolitan areas. Contemporary big cities, observes Kaplan, segregate neighborhoods by class, foster sameness of thought, and dull the senses with insipid architecture. Their rush and flow drown out the natural rhythms of human life while fostering a postmodern sensibility that sees meaning as fluid, ideas as objects to be constructed and deconstructed, and norms and rules in constant flux. Digital communications and social media empower urban elites, who are as disposed as any class to groupthink and the formation of echo chambers, to promulgate their prejudices as settled matters. Urban elites encourage imperial adventures as their big-finance and big-tech interests intertwine with developments in foreign markets and global supply chains. All the while, big-city life increases feelings of isolation and loneliness. This, Hannah Arendt and others have argued, and Kaplan emphasizes, fosters fear and resentment, laying the groundwork for mob behavior and totalitarian rule.

AI also makes possible and imperils the emerging global civilization. It promises great breakthroughs in medicine, engineering, and other technical realms while knitting the world more tightly together. At the same time, AI threatens to diminish individual responsibility by putting digital software in charge of moral and political thinking, and to suffocate freedom by providing an elite few with a powerful tool to control the masses.

While geopolitical trends are alarming, Kaplan insists that “better and worse outcomes are always available.” Better outcomes for the United States and the world, he maintains, depend on refusing to treat decline as foreordained, resisting the lures of the intemperance stemming from both left and right, and returning to the best of the classical liberal tradition. Embodied in America’s founding principles and the best of the nation’s constitutional heritage, that tradition affirms the dignity of the individual while taking account of human imperfection, teaches toleration for those competing views of the good life that themselves tolerate competing views, and recognizes that government’s primary task is securing equal rights under law.

Whatever one’s doubts about this or that element of Kaplan’s grave diagnosis of the condition of civilization, his proposed remedy should be adopted promptly.

The convictions and commitments that formed the United States remain essential to countering the present disorder.

Peter Berkowitz is the Tad and Dianne Taube Senior Fellow at Hoover Institution, Stanford University.

Politics

.webp)

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

This article explores Leo Strauss’s thoughts on Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1954 “Natural Right” course transcript.

%20(1).avif)

Long Distance Migration as a Two-Step Sorting Process: The Resettlement of Californians in Texas

Here we press the question of whether the well-documented stream of migrants relocating from California to Texas has been sufficient to alter the political complexion of the destination state.

%20(3).avif)

Who's That Knocking? A Study of the Strategic Choices Facing Large-Scale Grassroots Canvassing Efforts

Although there is a consensus that personalized forms of campaign outreach are more likely to be effective at either mobilizing or even persuading voters, there remains uncertainty about how campaigns should implement get-out-the-vote (GOTV) programs, especially at a truly expansive scale.

Joel Kotkin: Trump aside, Canada and the U.S. need to co-operate

Our economies are linked; we more the same language and we're learning that mass, unregulated immigration is no solution to economic sloth

Prosecuting Maduro

Much has been said about the expedient capture of Nicolas Maduro by American forces. Prosecuting him will not be so straightforward.

Peru: Between Chinese and American Influence

The U.S. government recently announced that it will designate Peru as a non-NATO military partner.