The Conserving Force of Lawyers in American Democracy

Law education should not rest in the hands of those who view the legal profession as the handmaiden to change and even revolution.

Editor's Note: Part of Civitas Outlook's "Texas and the Future of Legal Education" Symposium.

The Texas Supreme Court has taken the first necessary step in reforming legal education and restoring ideological balance to the legal profession. In April, it invited comments on whether to eject the American Bar Association (ABA) from its decisive role in approving Texas’s law schools. For the last four decades, only graduates of schools approved by the ABA have been able to join the bar and hence appear in Texas courts. This has enabled a political organization to exert an ideological influence over law schools, and as a result, attempt to bias the legal profession.

Entrance into the legal profession bears far more importance than the mind-numbing topics of accreditation and syllabi. Law schools dictate who enters the legal profession. Lawyers play a fundamental role in our democracy, a fact prominently observed by the great French thinker Alexis de Tocqueville. In Democracy in America, Tocqueville asked how our society had replaced the function of the aristocracy, which he believed played a welcome stabilizing influence over simple majority rule. Tocqueville concluded that in America, lawyers had filled the vacuum left by the absence of a European aristocracy.

Most famously, Tocqueville viewed lawyers as a moderating influence on mass democracy because of their way of thinking and the habits of their profession. Lawyers respect precedent and procedure, they accommodate political demands within an existing legal framework, and they enforce a Constitution that itself introduces important limits on democracy (separation of powers, federalism, and individual rights). In a world where Tocqueville concluded that democracy was sweeping away the ancient regime and sparking revolutions that could turn destructive, lawyers had tempered the effects of mass democracy. Tocqueville predicted that democracy, based on the equality of man, would prove an irresistible force, but one that could easily lead to the tyranny of the majority. There are few limits on the claims of democracy to rule, but in America, Tocqueville argued, the legal system and lawyers moderated the destructive passions of democracy.

Given the central role that lawyers play in our politics, control over their education bears directly on the success of American democracy. Law education should not rest in the hands of those who view the legal profession not as a conserving, moderating institution, but instead one that should serve as the handmaiden to change and even revolution. Unfortunately, that is what Texas and other states did when they handed over approval of law schools to the ABA. In the early 1980s, the Texas Supreme Court invited the ABA to accredit law schools for purposes of satisfying requirements to take the bar exam. Texas, for example, requires members of its bar to have completed their legal education at an “approved law school.” State law grants the authority to identify these law schools to the state Supreme Court, which, in turn, delegated this authority to the ABA in 1983.

This was a mistake. Delegating approval of a professional school to an organization might make sense if that body were devoted solely to establishing minimal national standards for practice. But the ABA does not meet that description. First, it is a membership organization, not a true professional organization. It does not select its members based on any criteria of excellence, knowledge, or achievement that would give it any claim to superior professional knowledge. Pay your annual dues of $120 and you are in. Once armed with your ABA card, you too can take advantage of group discounts from “trusted brands” for car rentals, hotels, and insurance. Currently, ABA membership can earn you $2,500 off a Mercedes-Benz and rebates on HP laptops and printers. Choosing between the ABA, AAA, and the AARP might demand careful thought.

Second, the ABA is not just a self-selected membership body (one that cannot even claim to represent half of all American lawyers); it is a political organization. It regularly takes positions on controversial political topics and lobbies government bodies to advance them. The ABA, for example, supported nationwide abortion rights under Roe v. Wade, race-based affirmative action, and other predictable elements of the Left’s platform. It cannot be trusted to fairly evaluate law schools if it takes positions on important ideological questions. We could not trust the ABA, for example, to accredit a law school that might have a large percentage of originalist faculty who believe that the Founders would have expected the states to decide questions of abortion.

A defender of maintaining the ABA’s exalted place might claim that the ABA’s views on ideological questions need not infect its performance of its official professional activities. But the ABA has not been able to resist the siren song of advancing its political agenda through its other roles. The ABA has sparked controversy with its effort to impose diversity requirements in the accreditation process. Its “Standards and Rules for the Approval of Law Schools” requires law schools to obey diversity, equity, and inclusion rules for faculty and students that plainly conflict with the Supreme Court’s ban on race-based affirmative action in Students for Fair Admission v. Harvard (2023).

The ABA requires law schools to provide “full opportunities for the study of law and entry into the profession by members of underrepresented groups, particularly racial and ethnic groups.” The Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause prohibits the state from providing exactly such benefits based on race and gender. The ABA also requires that law schools demonstrate “a commitment to having a student body that is diverse with respect to gender, race, and ethnicity.” Harvard bars state schools and schools that receive federal funds from composing a student body that uses race and ethnicity (and certainly gender too).

Despite the tenuous grounds for race-based affirmative action even before the Harvard case, the ABA was not reluctant to use its power over law schools to engage in racial engineering. As different accounts reported, in the early 2000s the ABA refused to accredit George Mason University law school unless it lowered its admissions standards for minority students in order to produce its desired levels of racial balance. The ABA did not even stop at admissions. It also requires law schools to design their curricula to advance the ABA’s progressive racial vision. Its “Standards and Rules for the Approval of Law Schools” demands that law schools “provide education to law students on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism” both at the start of the first year of law school and again before graduation.

The Trump Justice Department has sent a letter to the ABA demanding that it remove these racist standards from its accreditation work, and the Department of Education is considering whether to end the ABA’s monopoly over approving law schools. Under this pressure, the ABA has declared that it is suspending these offensive accreditation standards. But the ABA has not eliminated them. The ABA clearly will only defer its enforcement in the hopes that the Trump administration will lose interest or that a friendlier party will take office in three years.

These developments make it imperative that the Texas Supreme Court expel the ABA from its current role of approving law schools in the state.

John Yoo is a senior research fellow at the Civitas Institute, and a distinguished visiting professor at the School of Civic Leadership, University of Texas at Austin. He is also the Emanuel Heller Professor of Law at the University of California at Berkeley and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He serves on the board of the Pacific Legal Foundation, which has brought lawsuits against race-based affirmative action programs.

Politics

.webp)

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

This article explores Leo Strauss’s thoughts on Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1954 “Natural Right” course transcript.

%20(1).avif)

Long Distance Migration as a Two-Step Sorting Process: The Resettlement of Californians in Texas

Here we press the question of whether the well-documented stream of migrants relocating from California to Texas has been sufficient to alter the political complexion of the destination state.

%20(3).avif)

Who's That Knocking? A Study of the Strategic Choices Facing Large-Scale Grassroots Canvassing Efforts

Although there is a consensus that personalized forms of campaign outreach are more likely to be effective at either mobilizing or even persuading voters, there remains uncertainty about how campaigns should implement get-out-the-vote (GOTV) programs, especially at a truly expansive scale.

California job cuts will hurt Gavin Newsom’s White House run

California Governor Gavin Newsom loves to describe his state as “an economic powerhouse”. Yet he’s far more reluctant to acknowledge its dramatically worsening employment picture.

An anti-woke counter-revolution is sweeping through the media

From Hollywood to the newsroom, the hegemony of the ‘progressives’ is finally faltering.

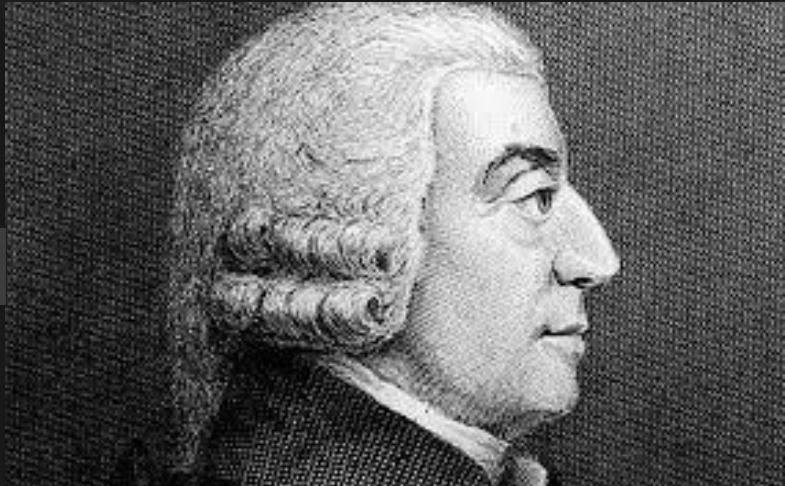

What Adam Smith’s Justice Teaches Us About Stealing Benefits

There is a constant tension in liberal systems between the shared trust necessary for the system's survival and the use of public entitlements paid for at public expense.

The Family Policy Symposium

How should we approach the problems of family formation and fertility decline in America?

%20(1).jpg)