Cicero's Law

A new book suggests that Cicero's relationship with the law was ambiguous.

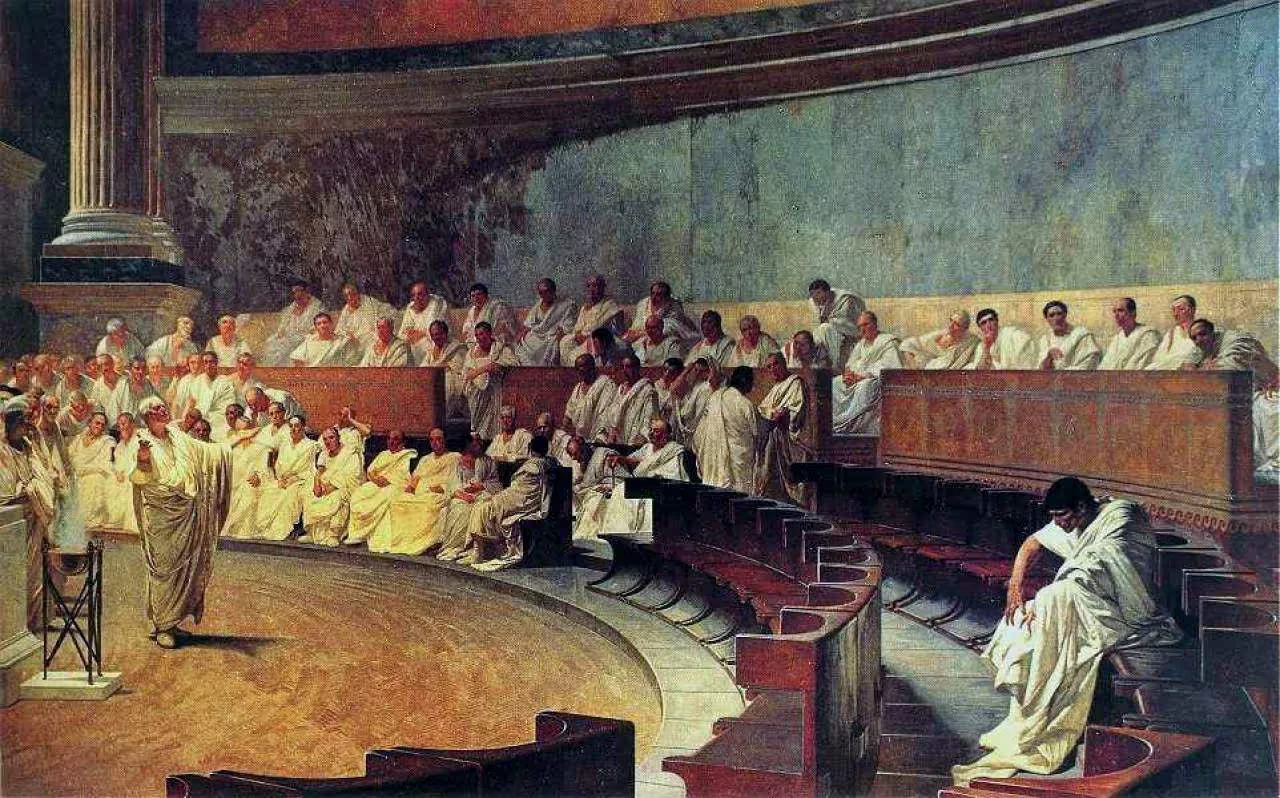

In 1939, the Oxford historian, Sir Ronald Syme, celebrated Cicero for his “enduring influence upon the course of all European civilization.” In the cinematic version of Roman history, the republican orator is pitted against the tyrant warrior, Julius Caesar. Georgetown’s Josiah Osgood dulls Cicero’s glow somewhat in his Lawless Republic: The Rise of Cicero and the Decline of Rome.

In Osgood’s telling, Cicero (106BC-43BC) is not a villain exactly but as an ambitious man with a “near-obsessive desire to be first,” he strategically clawed his way to the very top of the Roman Republic. On his way, he had no family pedigree to parley. He was what the Romans called a “new man” – the first in his family to attain Senate rank. Instead, Cicero used the theatre of the courts to showcase himself, and so ably that he became a consul of Rome in 63 BC. He not only defended scoundrels by hook and crook but, at the fateful moment, Cicero abandoned the courts, and turning to summary executions, he set the stage for the coming to power of the emperors, the Roman Revolution that would destroy him.

Lawless Republic is not about Cicero’s many contributions to rhetoric and ethics, nor the intricacies of Roman law, but the story of the trials Cicero used to make good on his political advancement. As the book title suggests, Osgood concludes that for all his love of the courts, Cicero’s legal practice helped weaken the rule of law and make violence the political currency of Rome.

First Case

The backdrop to Cicero’s early career was civil war and the dictatorship of Sulla. The wealthy enemies of Sulla were proscribed, which, along with killings, meant the stripping of family property. The beneficiaries were Sulla’s chums and even slaves. Slaves could kill patricians for a reward should their masters appear on Sulla’s outlaw list. The proscriptions, comments Osgood, “cut asunder the ties that held Roman society together, even the most sacred.” They normalized the plunder of the citizenry, which gave Cicero the opening to begin his climb.

An unknown at the courts, Cicero took the case of Roscius junior, a man accused of parricide. To say Rome was a rough place is an understatement. An indication is that the crime of homicide was of late vintage. The Latin word for the killing of a father is much older than the Latin for homicide, Osgood tells us. How Romans viewed the gravity of each is evident from the punishments: convicted of murder, exile followed, but parricide was thought to pollute the res publica, and the sentence was death.

Cicero argued the case and showed he had a talent for spinning story lines and reversing assumptions. In the matter of the killing of Roscius senior, Cicero argued the case was not about the killing of a father at all, but rather, both father and son were victims of the proscriptions. He accused Lucius Chrysogonus of the murder. A freedman of Sulla’s, Chrysogonus had become enormously wealthy. He bought the dead Roscius senior’s estates at a bargain basement price.

Whilst modern trials concern the innocence or guilt of a person, it was standard practice in Rome to try to pin the blame on another. To make the accusation stick, Cicero leaned into prejudice. As Osgood puts it, “leading Romans thought that no ex-slave should have so much money or power.” By arguing that Chrysogonus was the murderer, Cicero bravely implicated Sulla’s camp and effectively argued that the dictator had not restored law after the civil war. He closed his case with the warning that if the jurors did not acquit Roscius junior then the predation of men like Chrysogonus, so far done in secret, would soon unfold in the open of the Forum itself. The young Cicero won his first case, and people took notice.

Osgood points out an irony. Sulla’s politics were to restrict populism and restore rule to the great families. Cicero shared this politics. His whole career affirmed “his belief in the established social and political order, and his conviction that property was sacred above all.” Cicero was always careful to pay back his wealthy supporters with sinecures, and his time in office gave no solace to commoners.

Career-Making Case

In Rome, there was neither police nor public prosecutor. Private individuals brought charges and could employ an advocate. At Sulla’s time, there were seven courts with juries made up of senators. The courts heard cases about the crimes of treason, extortion, electoral malpractice, embezzlement, forgery, assault, and murder. Most prominent was the extortion court. Osgood relays that “extortion was the ultimate high-class crime” and was largely concerned with the misdeeds of governors.

Rome prioritized its own over foreigners, and the extortion court was the only way foreigners got redress for abuses. It was a tough hill to climb. The language of the court was Latin, and foreigners were not held in high regard. Specifically, Greek witnesses were routinely attacked as liars, heirs of the Trojan Horse ploy. Since evidence was hard to come by and courts were held in the open on the Forum, theatre was basic. Lawyers indulged the crowd with their favorite “stereotypes about social status, ethnicity, and gender.” Cicero was particularly adept. All of this was fair game, and the point was to gin up the crowd’s emotions. Cicero routinely worked himself up into tears towards the end of court speeches.

The prosecution of the extortionist, Gaius Verres, made Cicero’s career. Verres was a compulsive art collector and during his various governorships, he pinched art from persons, temples, and cities. Redress was difficult because the principal job of a governor was military, so great latitude of rule was permitted, lest the conquered get restive. Thoroughly sick of Verres’s art mania, the leading persons of Sicily hired Cicero. Cicero went to Sicily for two months to gather evidence and witnesses. He also found Roman witnesses. One that startled the jurors was a high-born Roman matron. She was especially effective because women were seldom seen in the Forum. Osgood describes her impact: “Verres, it seemed, would rip off anyone.”

Though powerful friends protected Verres, the tide was against him. Romans would forgive rampant thieving from foreigners if the loot led to public games, but Verres was an obsessive, pawing his beloved artefacts in private. To the Roman mind, “a criminal was a man bent on satisfying his own pleasure rather than the public good.” Sensing the jig was up, Verres fled. Cicero’s victory was complete. He was flooded with work, and Cicero, as he wrote, found himself “burning the midnight oil.”

Case Closed

Triumphs and advancement followed, but disaster also.

A competitor for the consulship of 63 BC, Lucius Catiline needed the top office to pay off creditors. Losing, he fomented a conspiracy to subvert the government. Cicero ably rallied the Senate, but he ignored Caesar’s warning that execution without trial offended the rights of every Roman citizen. Warned of a backlash, Cicero barreled on regardless and hung the conspirators.

As Caesar predicted, the backlash came, and Cicero’s star waned. He compounded the problem of runaway political violence in his defense of Titus Milo. The well-placed Milo – he was married to Sulla’s daughter – was accused of the murder of the popular but scandalous Publius Clodius. Initially, Cicero argued that the killing of the scion of one of Rome’s most august families was self-defense but later he advanced the dark argument that killing is righteous, if it serves the res publica. Osgood cautions: “But a widespread belief that there is a higher power than human law that justifies murdering your enemy spells trouble for civil society.”

Oddly, the killing was most likely inadvertent. The prevalence of political violence meant that prominent Romans hired roughneck gangs, and when the people of Milo happened to run into Clodius’s people, mayhem ensued. Amidst the political “fog of war,” Cicero lost. The case's notoriety “proved to be a milestone in the final collapse of republican government in Rome.” Marcus Brutus published a pamphlet about the trial and celebrated Cicero’s reasoning about the higher law. “Cicero had helped to bring on forces,” comments Osgood, “that would ultimately kill him and destroy the Republic.” Though Cicero was not involved in the plot against Caesar, he was the most vocal supporter of Brutus. The Second Triumvirate cleaned house, and that included dispatching Cicero.

Lawless Republic is the story of the life and times of Cicero, Osgood concluding: “He tried to use the word to persuade, rather than the sword to arbitrate.” Osgood does not zoom out to wider historical lessons, morals, and principles of law. The indirect lesson is that holding fast to our rule of law is essential, for Osgood never lets you forget that Roman politics was brutal. Then, the law was marginal. In “the relentless pursuit of wealth and power by the upper classes of Roman society,” one thing was invariant – “cutthroats got ahead.”

Graham McAleer is lay member of the Judicial Ethics Committee of the State of Maryland and author, most recently, of Tolkien, Philosopher of War (CUA Press, 2024).

Politics

.webp)

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

This article explores Leo Strauss’s thoughts on Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1954 “Natural Right” course transcript.

%20(1).avif)

Long Distance Migration as a Two-Step Sorting Process: The Resettlement of Californians in Texas

Here we press the question of whether the well-documented stream of migrants relocating from California to Texas has been sufficient to alter the political complexion of the destination state.

%20(3).avif)

Who's That Knocking? A Study of the Strategic Choices Facing Large-Scale Grassroots Canvassing Efforts

Although there is a consensus that personalized forms of campaign outreach are more likely to be effective at either mobilizing or even persuading voters, there remains uncertainty about how campaigns should implement get-out-the-vote (GOTV) programs, especially at a truly expansive scale.

There's a Perception Gap With the U.S. Economy

As we approach another election cycle, it’s worth asking: what’s real, what’s political theater, and what does it all mean if Democrats regain control of the House?

International Law Is Holding Democracies Back

The United States should use this moment to argue for a different approach to the rules of war.

Trump purged America’s Leftist toxins. Now hubris will be his downfall

From ending DEI madness and net zero to securing the border, he’ll leave the US stronger. But his excesses are inciting a Left-wing backlash

California’s wealth tax tests the limits of progressive politics

Until the country finds a way to convince the average American that extreme wealth does not come at their expense, both the oligarchs and the heavily Democratic professional classes risk experiencing serious tax raids unseen for decades.

Storm Over the Appointment Process

This is not your grandfather’s appointment process; in fact, it’s not even your older brother’s.

The Clash of Civilizations at 30

Three decades on, Huntington did not foresee the extent to which the West would erode, but he did perceive the warning signs.