.avif)

Accrediting for Tomorrow: Law School Metrics and Interstate Compacts

Current ABA accreditation has established a common floor for bar admissions and federal loan guarantees, creating a nationally portable credential. Yet that success has created significant costs.

Editor's Note: Part of Civitas Outlook's "Texas and the Future of Legal Education" Symposium.

The American Bar Association’s (ABA) monopoly over law-school accreditation once guaranteed national portability and a baseline of quality. However, this monopoly is increasingly facing political challenges and growing discomfort, particularly concerning its influence over curriculum, costs, and diversity standards. This essay sketches a complementary pathway—grounded in transparent metrics and stitched together by an interstate compact—that would enable willing states accredit on outcomes, not just prescriptive inputs, while preserving rigorous public protection.

The ABA’s Strength—and Strain

Current ABA accreditation—with its exhaustive data collection, self-studies, multi-day site visits, and growing standards manual—has established a common floor for bar admissions and federal loan guarantees, creating a nationally portable credential. Yet that success has carried at least three significant costs.

First, latency. Because comprehensive visits are expensive and thus occur only once every ten years, problems that emerge in year two may lie fallow until year eight, when frantic remediation begins. The ABA’s interim questionnaires supply information, not nimble oversight: the Council seldom intervenes unless disaster is already visible.

Second, mission drift and questionable return on investment (ROI) on standards. Recent standards have, at times, reached beyond core academic and professional competence, pressing schools toward particular ideological commitments or specific visions of social policy, raising concerns about politicization and insufficient attention to intellectual diversity. Moreover, there is a notable absence of published studies linking ABA accreditation or satisfaction of many individual ABA standards—say, the mandate for “programmatic learning-outcome review every five years” (Standard 315(b))—to improved bar passage, employment, or civic engagement once incoming student credentials and resources are controlled for. Would eliminating such a standard truly result in worse attorneys when outdated curricula would likely be captured by other, more outcome-focused metrics, such as bar passage or employment?

Third, there is a profound lack of transparency. The detailed findings, site evaluation reports, and even the specific reasoning behind certain accreditation decisions—documents that critically determine a law school's standing, its graduates' eligibility for the bar, and student access to federal loans—are not made available to the public or even to the broader faculty of the institution under review. It's thus hard for the public to insist on reforms or to assess the biases of site visit teams.

None of this counsels immediate abolition. It does counsel choice.

An Outcome-Based Safe Harbor

Suppose the regulatory authorities of State A were to accredit a law school annually if transparent, publicly verifiable data showed that (a) at least 75 percent of first-time takers passed the bar over a rolling three-year window, (b) a super-majority of graduates secured JD-required or JD-advantage positions within ten months, and (c) graduates’ median debt-to-income ratio two years out did not exceed a specified ceiling. To blunt curriculum-narrowing, the state might also require proof that most students have completed a minimum menu of non-bar courses—tax, immigration, intellectual property, or bankruptcy, for example, with the regulatory authority potentially setting numeric thresholds for such course completion.

Schools clearing every threshold could offer their graduates eligibility for the State A bar even if they declined the ABA’s process. Far from forcing anyone’s hand, the safe harbor would run parallel to the traditional route: a school satisfied with ABA accreditation remains free to stick with it, and a risk-averse applicant need only choose such a school.

Goodhart’s Law—and How to Survive It

The gravest objection to metric-driven oversight is Goodhart’s Law: when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. A school could, in theory, strip its elective curriculum to the bone, teach nothing but bar topics, and march graduates through commercial prep courses. Yet several considerations soften that worry.

First, markets are multi-dimensional. Employers who rely on new associates for tax, IP, or immigration advice will likely shun graduates who are steeped solely in evidence law. Market feedback can act as a natural corrective.

Second, the feared distortion is incremental, not novel. The ABA system already privileges bar passage indirectly through Standard 316. The U.S. News & World Report ranking incentives, which dominate admissions marketing, already induce many schools to place a heavy emphasis on bar passage.

Third, a portfolio of metrics disciplines can lead to tunnel vision. Pairing bar success with employment outcomes, debt-to-income ratios, and curricular-breadth requirements (such as minimums for diverse non-bar course completions) turns bar-only optimization from a vice into a virtue. An intelligently designed algorithmic system could proactively address this.

In short, Goodhart bites hardest when regulators choose a solitary number and stare at it. A balanced dashboard turns the maxim into design guidance rather than a fatal flaw.

Why a Compact Is Indispensable

But wouldn't a state-based algorithmic accreditation system both trap students in their own states, just as was the case before the ABA emerged as a monopoly accreditor? Not necessarily. A legal education compact could cure the problem.

A legal-education compact entered into by a group of states would specify: (1) the minimal reliability and core principles of educational quality required of any member’s algorithm; (2) a verification protocol, including random third-party audits of underlying data to ensure integrity and prevent manipulation; and (3) automatic reciprocity once verification is confirmed—so that a graduate of an algorithmically accredited school in State B may sit for State A’s bar without additional hurdles (and vice-versa). Governance could rest in a small commission comprising deans, judges, and public members, whose reports are published in full, ensuring independence and expertise.

Such a structure marries local experimentation to interstate mobility: any state may pioneer a metric it deems valuable, yet no state needs to accept another’s algorithm until it passes the common test of transparency and validity.

Likely Benefits and Predictable Objections

A. Benefits

An outcome-based pathway compresses the feedback loop from a decade to a year, allowing regulators to detect slippage early and students to vote with their feet. It lowers fixed costs—particularly for innovative providers like distance-learning programs whose facilities might never satisfy the bricks-and-mortar emphasis of current site visits—potentially leading to more affordable legal education models. Furthermore, such a system could be more flexible in recognizing programs that cultivate evolving competencies needed in a legal profession being reshaped by technologies such as AI. Indeed, much of the expensive faculty required by ABA accreditation standards could likely be replaced by AI soon.

B. Objections

Skeptics will cite data integrity and the temptation to “teach to the algorithm.” Both are real, but neither is unique to this model. Others may reasonably worry whether quantitative metrics can truly capture all essential elements of being a competent and ethical lawyer, such as critical thinking, ethical judgment, client counseling, and negotiation. In an age of ever-evolving AI, however, where machines can sensibly evaluate essay examinations or perhaps even live human performances, it might well be possible to develop additional inexpensive testing mechanisms that measure these additional skills better than ABA accreditation requires.

There are further complexities that this short essay cannot fully address. Developing initial algorithms, data infrastructure, and interstate compacts involves initial costs and complexity. Who would bear these costs? Moreover, even once accreditation rules were in place, a system would have to be developed for new schools and provisional accreditation: you can't measure employment or bar passage where none of your students have yet gotten a job or taken the bar. Perhaps the new school could show through a predictive model that, given the credentials of its admitted students, satisfaction of algorithmic criteria is likely.

Conclusion

Professional licensure seldom rewards innovation; path dependence is its defining instinct. Politics, economics, and technology have combined to question the continuing ABA monopoly. Transparent, multi-metric accreditation administered annually and recognized across a compact of like-minded states promises faster correction of institutional failure, lower tuition, and the freedom for new entrants to experiment without first mustering a decade’s worth of operating cash. But the proposal neither abolishes the ABA nor consigns its standards to irrelevance. Indeed, even established institutions might opt into dual accreditation, using annual metrics as an early-warning system while retaining ABA status for prestige and as a belt-and-suspenders device. The proposal merely restores what federalism has always offered American education and professional training: competition based on merit.

Seth J. Chandler is a professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center. He has served on ABA site-evaluation teams and writes on insurance law, AI, and the application of data analytics to regulation. The views expressed are his own.

Politics

.webp)

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

This article explores Leo Strauss’s thoughts on Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1954 “Natural Right” course transcript.

%20(1).avif)

Long Distance Migration as a Two-Step Sorting Process: The Resettlement of Californians in Texas

Here we press the question of whether the well-documented stream of migrants relocating from California to Texas has been sufficient to alter the political complexion of the destination state.

%20(3).avif)

Who's That Knocking? A Study of the Strategic Choices Facing Large-Scale Grassroots Canvassing Efforts

Although there is a consensus that personalized forms of campaign outreach are more likely to be effective at either mobilizing or even persuading voters, there remains uncertainty about how campaigns should implement get-out-the-vote (GOTV) programs, especially at a truly expansive scale.

California job cuts will hurt Gavin Newsom’s White House run

California Governor Gavin Newsom loves to describe his state as “an economic powerhouse”. Yet he’s far more reluctant to acknowledge its dramatically worsening employment picture.

An anti-woke counter-revolution is sweeping through the media

From Hollywood to the newsroom, the hegemony of the ‘progressives’ is finally faltering.

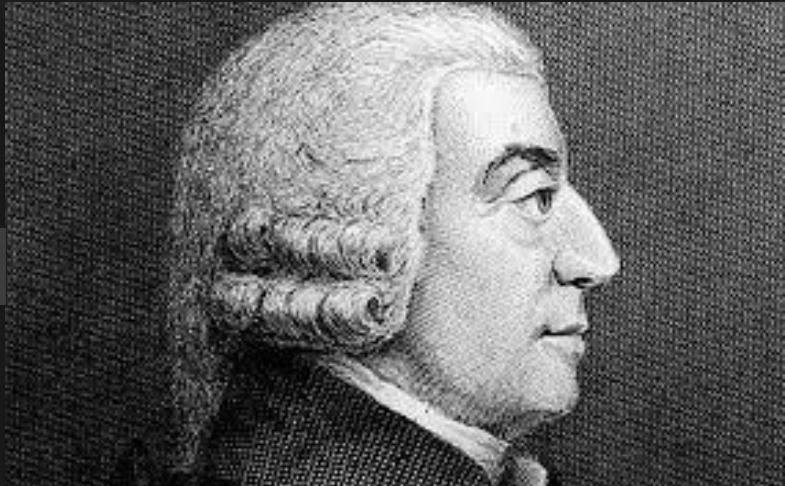

What Adam Smith’s Justice Teaches Us About Stealing Benefits

There is a constant tension in liberal systems between the shared trust necessary for the system's survival and the use of public entitlements paid for at public expense.

The Family Policy Symposium

How should we approach the problems of family formation and fertility decline in America?

%20(1).jpg)