Beyond the Melting Point: Exodus, the Sequel

The Melting Point describes how, decades before the establishment of Israel, Jews scattered throughout the world for two millennia managed to rediscover one another.

First released in the UK in 2024 to great acclaim, Melting Point: Family, Memory, and the Search for a Promised Land has just been published in America, where an equally enthusiastic reception is all but guaranteed. The praise for its previously unknown young author, Rachel Cockerell, is well deserved. Having set out to explore her family’s roots, she soon stumbled upon a treasure. Their cosmopolitan odyssey turns out to have played a far greater role upon the stage of history than she had ever imagined.

In brief: After their parents emigrated from Russia, the author’s Lithuanian-born mother, Fanny, and her sister, Sonia, both married in England – the former to an Englishman, the latter to a Russian-born Zionist Jew. Fanny’s four children included Rachel’s father Michael; Sonia’s were Mimi, Judy, and Dan. Plot surprise: Rachel’s great-grandfather, who becomes the book’s main, if elusive, character, had been (unhappily, it seems) married before to Rivka, with whom he had a son, Emmanuel Jochelman. Changing his name to Emjo Bassche, he had emigrated to America at the age of 14; it would be his daughter, Jo, who introduced Rachel to Sonia and her family, who were by now in Israel.

It’s a complicated story that isn't very clearly conveyed. (Jews in exile - what do you expect….) Fortunately, this is not mentioned until the middle of the book. This allows Rachel to begin on a very high note. Most deeply moving is her revelation of the appallingly understudied and widely misunderstood origins of modern Zionism, whose purpose was to save their co-religionists from near-annihilation.

It would be churlish, therefore, to fault this remarkable author for having missed the full significance of her own title, “Melting Point.” Its obvious reference to the problem of assimilation, immigration, and identity is indisputably critical, but not the main point, so to speak. The deeper story is nothing less than a twentieth-century follow-up of Exodus and its sequel, Numbers. The latter’s message is captured concisely by Rabbi W. Gunther Plaut in these words: “The harsh environment of the wilderness led to Israel's spiritual development as a nation.” The “harsh environment” of this new book is the two-millennia prequel to the Holocaust.

Cockerell would undoubtedly agree, for she appreciates that any creation only gradually reveals itself to its author. As she admitted to Andrew Silow-Carroll of the Jewish Telegraph Agency (JTA) on April 24, 2025:

It was only about a year in that I realized that this is the story of assimilation and of melting into the melting pot for Jewish immigrants. But I think it’s also a universal experience of leaving a place and arriving in a new place, and part of your identity changing or dissolving away. My family definitely melted into the melting pot of London.

Except that a melting pot should not imply merging diverse cultures, languages, and creeds inside a homogenizing figurative Cuisinart into a bland gruel of meaning-less coexistence. A true Promised Land, albeit necessarily a territorial one, has its true locus within. She goes on: “You know, I think of myself as British, as a Londoner, more than I think of myself as Jewish or Russian or Russian Jewish.”

“Leaving a place and arriving in a new place”….. No refugee from pogroms or the SS or the KGB, usually leaving behind family members to all-but-certain extinction in unimaginable ways, could write so casually about the agony of heading into a place that is not merely “new” but utterly unknown, even nonexistent. Statelessness. Yet it is that very condition that is itself bonding, a cohesion molded through pain, a fusion, merging, steeling. This book describes how, decades before the establishment of Israel, Jews scattered throughout the world for two millennia managed to rediscover one another. They had to understand that they constitute a people, a nation - perhaps in their original homeland, but if need be, beyond its borders.

It is to Cockerell’s great credit that she rewrote her book after realizing she had to allow the story to unfold naturally; she had to let the story write itself. An unusual work of expressionist nonfiction, told “by collaging excerpts from primary documents” and personal interviews, her book has been deemed “unclassifiable,” “dazzling,” in sum, “an innovative and immediate account of a story that has world-historical significance.” All true.

That story begins with Theodore Herzl, a Hungarian-born German-speaking Reform Jew whose 1896 book Der Judenstaat ('The State of the Jews') was prompted by the Dreyfus Affair that had just exploded in France. Clearly, neither East nor West was safe for Jews, Herzl’s book intoned. The book exploded like wildfire. As Israel’s first president, Chaim Weizmann, would say of this latter-day Moses: “He became a monumental, mythical Jewish figure – something of a legend. … The [book’s] message was soon passed on to every town, great or small, in Poland and Russia in which a Jewish ghetto existed.” The larger world heard it too. The Jersey City News, with typical American optimism, would report: “That one watchword, the ‘Jewish State,’ has been sufficient to rouse the Jews to a state of enthusiasm in the remotest corners of the earth.”

Far less widespread was any awareness of the agony fueling the ecstasy. Herzl, however, felt both, and with excruciating urgency. Wasting no time, he enlisted as his brother-in-arms (the Aaron to his Moses), the British-born son of Russian Jews, Israel Zangwill. The most famous Jew in the world.

Never having met before, the two became fast friends almost instantly. They both had first-hand experience of the sectarian chasms bisecting the Diaspora. Born at the crossroads between east and west in Austro-Hungarian Pest, Herzl knew that the Ashkenazi Orthodox, mostly poor and rigid in their habits, had almost nothing in common with the successful, wealthy, German-speaking Jews who hoped for future assimilation into the gentile world (even as they often hated themselves for it). While the former were afraid to leave for fear of being polluted by apostasy, the latter’s contempt for their uncouth brethren blinded them to the antisemitic flood about to drown them all.

Israel Zangwill not only understood but managed to convey it to Western audiences through his masterpiece Children of the Ghetto: A Study of a Peculiar People. Blending subtle humor with heart-wrenching tragedy, it created a sensation in both England and America upon its publication in 1892, to be exceeded only by his eponymous play, “The Melting Pot.”

The two ideal partners set out to convene the first Congress of a movement Herzl called Zionist, which he defined as “a return to Judaism even before there is a return to the Jewish land.” Meeting first in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897, 1898, and 1899, then in London in 1900, and returning to Basel in 1901, it attracted no fewer than 500 delegates from every corner of the diaspora. All the while, pogroms intensified, the flood waters rising by the day.

And then, there was Kishinev. The brutal slaughter of defenseless Jews in that ancient Russian-Moldovan city on April 8, 1903, elicited this reaction from Theodore Roosevelt: “I have never in my experience in this country known of a more immediate and deeper expression of sympathy for the victims and of horror over the appalling calamity.” Zangwill: “The only solution of the Jewish question is to take the Jews out of Russia, and plant them in a soil of their own.” Now.

But where? A few months later, at the historic Sixth Congress held in Basel, Herzl revealed that Kenya (which a British MP had casually mistaken for Uganda) might be a possibility. But it wasn’t up to him; he had to put it to a vote. As he had feared, the Jews who stood in greatest danger, Ashkenazim from Russia, would consider nothing but Palestine. They did so while falling on their knees, weeping. Such was the noble fodder of Hitler’s ovens.

Herzl was devastated. He was convinced that Palestine could never accommodate all the Jews facing genocide – millions perhaps? How could at least a temporary solution not be acceptable? Equally exasperated, Zangwill told the delegates bluntly: “We must have a home and a refuge for those of our brethren who are the victims of Kishineffs, and, if we wait much longer, who knows but that there will be none left alive to reach that home.” Was the Jewish world to be so divided against itself as to risk extinction? Herzl would never recover from the blow. Within a few months, he would be dead. Like Moses, he would not live to see the promised land.

The Congress was as split as its constituents, with one wing open to considering options other than Palestine, which would be called the Jewish Territorial Organization (ITO). David Jochelman managed to convince Zangwill to head it up. They would send a delegation to explore possibilities. As could have been predicted, it soon transpired that not only did the Uganda/Kenya option evaporate, so did every other. Having combed every continent, the ITO delegation concluded that the gentile world would never allot to the Jews even a sliver of territory to govern themselves. The world proved Pharaonic.

Only one nation was still left: the United States. For the last two centuries, nowhere else had Jews been as welcome. Having shared the covenantal creed that four decades later would inspire Israel’s Declaration of Independence, the United States had recently been declared by its martyred philosemitic president, who had sought to emulate Moses, Abraham Lincoln, “an almost chosen nation.”

Zangwill knew that Jochelman was perfectly suited to organize the orderly evacuation of Jews to America, but they needed money. Coincidentally (maybe), Zangwill had another good friend he had met in London, whose assets extended beyond intellectual and moral. Indeed, according to The Philadelphia Press, he was “the most powerful force of any of the so-called high-financiers of New York.” His name was Jacob J. Schiff. That he was the right man is clear from the description of his vision, published in The American Hebrew of 1907, of

[a] people among the best in the land, proud of their American citizenship, thoroughly imbued with its spirit, with its obligations, with its high privileges, but just as proud of their religion – almost a new type – true Americans of the Jewish faith.

Unlike everywhere else, abandoning one’s religion was no requirement for citizenship.

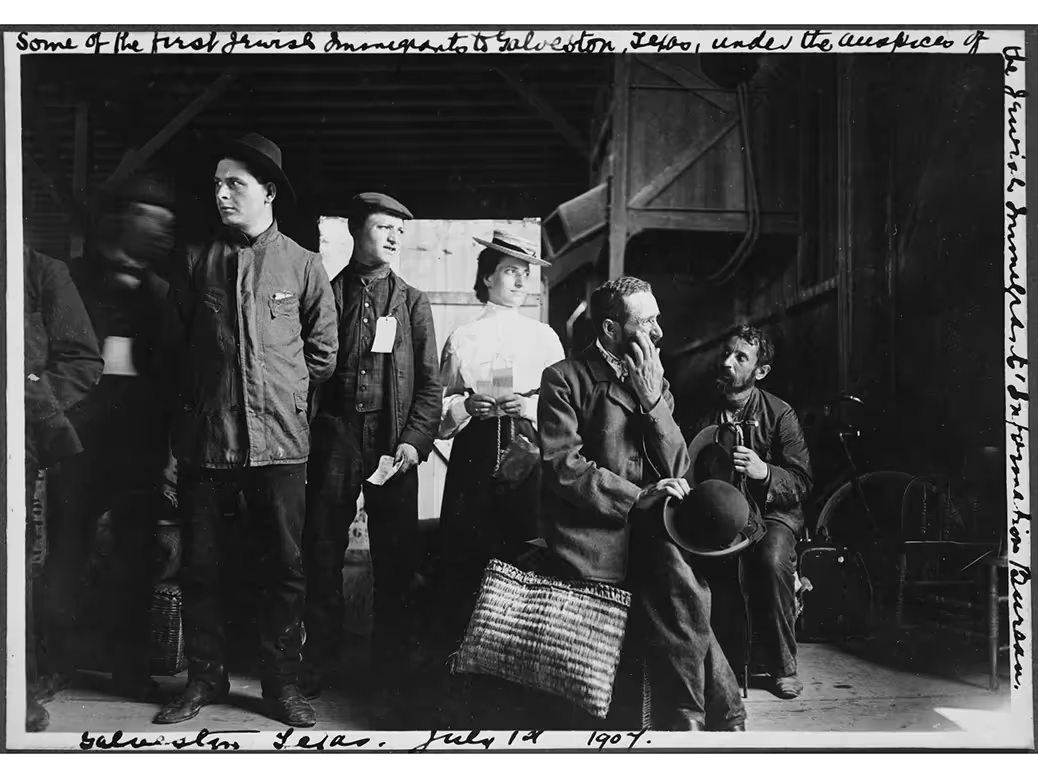

Now for a point of entry. By process of elimination, the choice fell upon Galveston, Texas. Strategically placed landing site for vessels carrying the endangered cargo, it was also the home of Zangwill’s former classmate and good friend: its rabbi, Dr. Henry Cohen. Alongside his kind wife, the rabbi’s reputation was legendary: “When people were in trouble, white or black, Jew or Gentile, aristocrat or plebeian, it was ‘the Rabbi’ who was first consulted.” A prototypical chosen good Samaritan.

Cockerell’s great-grandfather rose to the occasion despite being seriously ill. Having established some 150 offices throughout Russia to facilitate Jewish emigration, he thereby gained a place of honor among the prophets of the new state of Israel. But he, too, would die before its founding, in 1941 – an almost silent prophet.

His family’s subsequent odyssey takes up the rest of Cockerell’s unusual book. She turns first to the New York family of David’s son, born to his first wife, Rivka. Emmanuel Jockelmann (pen name: Emjo Basshe), a talented playwright and partner of John Dos Passos and two other Jewish writers, a protegee of the great philanthropist Otto Hermann Kahn. Emjo married a philosemitic Southern-born Christian actress, whose daughter Emjo Basshe II (Jo), a journalist, whom Rachel discovered in Canada, where she had retired along with her husband, a gentile Columbia University professor.

Only then does Rachel turn to her own English family, home of Fannie and Sonia Jochelman, David’s daughters with his second wife Tamara, their respective husbands - the amiable Englishman Hugh Cockerell (Tamara’s) and the staunch Zionist Yehuda Behari, whom Sonia had promised to accompany to Israel when possible – and all of their children. Diverse personalities, political orientations, theological inclinations, whose idiosyncrasies alternately enlivened and soured their lives, they were a colorful mélange.

Though seen only superficially through snippets of interviews and background documentation, the reader is intrigued by their rambling lives, none of which is ultimately fulfilling for various reasons. But above all, what is clearly missing is any sense of Judaic identity. Even Jochelmann’s son-in-law, Yehuda Benari, who became the right-hand man to the great Ze’ev Jabotinsky, “knew absolutely nothing about Judaism,” according to his oldest daughter, Mimi. “He was brought up without it, so it was never part of his life.”

Did he also fail to teach them history? As Mimi’s younger sister Judy told Cockerell, it wasn’t until years later, after they arrived in Israel, that “I realized they weren’t really kept adrift of what was going on: that the Arabs were being thrown out of their homes, and their country.” Today, the author says, “I don’t know who has claim to this land, I don’t think anybody really knows. But it’s obvious that the Palestinians didn’t leave, they were thrown out. Who would want to leave their home?”

She could have asked the same of the Jews expelled from Arab lands. But there is no mention anywhere in this otherwise fine book of the Balfour Declaration; the Arab rejection of the Partition Plan; the unprovoked wars of 1967, 1973, and constant terrorism; Oslo and the Intifada; Hamas, Iran. There is no hint that Cockerell knows. Maybe it just succumbed to the editor’s cut?

The book ends on a nostalgic note. In the Afterword, Cockerell writes that despite regular annual visits to Israel since 2018, she always feels “like an outsider.” But maybe less so as time passes. For as she admitted on May 5, 2025, to Casey Schwartz of the Washington Post: “It made me realize everything that my side of the family didn’t have. Everything that my side of the family had lost.” Lost, but cherished still.

The answer for her and others like her in the Jewish diaspora may well be right there, in the motto to her book. Written by the one man whom Rachel says had “won a place in my heart, perhaps more than any other character," Israel Zangwill, it says: “If we cannot get the Holy Land, we can make another land holy."

That is the third Moses also wouldn’t live to witness the Jews’ national revival, which seemed – because it was – a sheer miracle. What would not surprise any of them is the massive escalation in antisemitism. But now the Jewish state is here. Its presence reminds the rest of the world that their long-suffering people’s mission extends to any nation that believes all human beings to have been created equal in God’s Image. All we need is family, memory, and the hope that someday no one need be a slave again. America, of all places, should get it.

Juliana Geran Pilon is Senior Fellow at the Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization. Her latest book, An Idea Betrayed: Jews, Liberalism, and the American Left, has just been published.

Pursuit of Happiness

The Rise of Latino America

In The Rise of Latino America, Hernandez & Kotkin argue that Latinos, who are projected to become America’s largest ethnic group, are a dynamic force shaping the nation’s demographic, economic, and cultural future. Far from being a marginalized group defined by oppression, Latinos are integral to America’s story. They drive economic growth, cultural evolution, and workforce vitality. Challenges, however, including poverty, educational disparities, and restrictive policies, threaten their upward mobility. Policymakers who wish to harness Latino potential to ensure national prosperity and resilience should adopt policies that prioritize affordability, safety, and economic opportunity over ideological constraints.

Exodus: Affordability Crisis Sends Americans Packing From Big Cities

The first in a two-part series about the Great Dispersion of Americans across the country.

The AI Future: Between Certain Doom and Endless Prosperity

AI continues to become more complex and sophisticated, but public policy solutions do not.

The Castle, the Cathedral, and the College

Our civilization struggles to explain why anything should command allegiance beyond preference or power; its remnants echo a grandeur now distant.