Regulatory Costs Ensure the Housing Sector Can't Thrive

Reducing regulatory barriers and boosting construction-sector productivity is not merely a housing-market issue—it's a national economic imperative.

In 1984, the median sales price of a home was roughly 3.5 times the median household income. Forty years later, that ratio has climbed to about 5.3 times the median household income. Why has housing become so much less affordable?

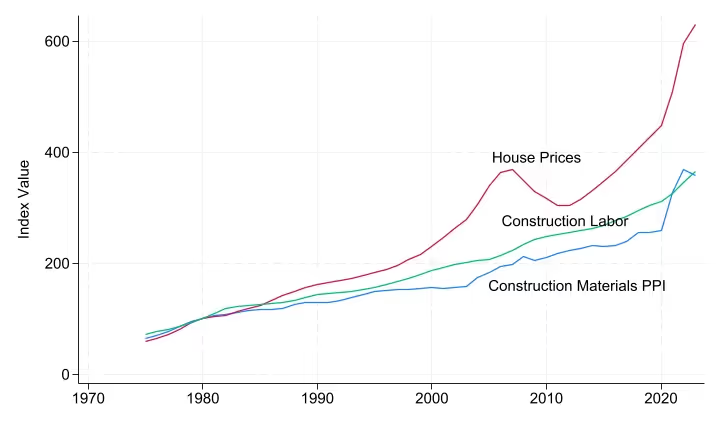

One potential explanation is rising materials or labor costs. While these costs have certainly increased, they have not kept pace with the rapid rise in housing prices (see Figure 1). What, then, is driving this growing gap?

Ed Glaeser and Joe Gyourko suggest that the wedge between housing prices and construction costs indirectly measures the "regulatory tax" on development. In other words, if competitive markets normally price housing close to construction costs, then large, persistent gaps between these two figures signal the presence of explicit and implicit regulatory costs.

Estimates of these regulatory costs are significant, especially in high-cost metropolitan areas. Simulations of reforms designed to reduce these costs often predict substantial effects. For example, a recent study by the Terner Center at UC Berkeley found that a policy mix of increased allowable density, reduced parking requirements, and streamlined entitlement processes would double the number of units constructed in a high-cost city like Los Angeles.

Empirical examples reinforce the point. In Austin, Texas, a surge in permitting activity following COVID has driven rents downward. In Auckland, New Zealand, a comprehensive 2016 upzoning plan triggered a building boom that caused rent-to-income ratios to decline significantly, even as these ratios rose across the rest of the country.

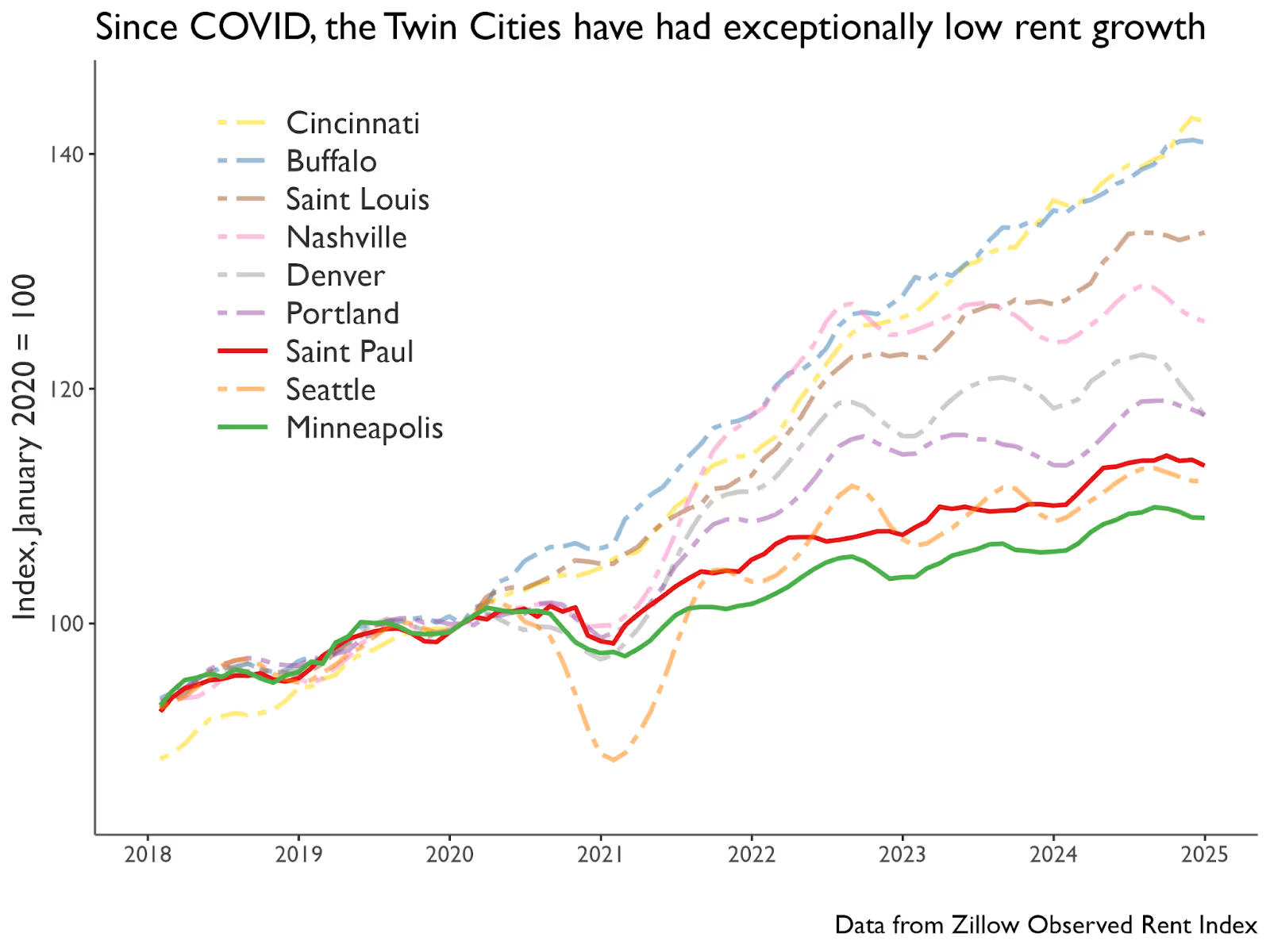

However, not every reform has produced similarly dramatic results. California's widely publicized SB9, which enables homeowners to build up to four homes on a single family parcel, has so far delivered underwhelming outcomes. Similarly, the evidence on Minneapolis’s 2018 zoning reform is mixed. Whereas skeptics of the plan point to initially disappointing recent permitting data, defenders note that Minneapolis rents have remained relatively stable compared to those in comparable cities. Disentangling the true impact of these reforms is complicated by concurrent changes in materials costs, interest rates, and other demand factors. For instance, Minneapolis simultaneously implemented stronger tenant protections, which may have dampened multifamily investment.

These mixed results underscore the complexity of regulatory costs and the ways they interact with one another. Removing one development barrier may accomplish little if other obstacles remain in place. Similarly, what constrains construction in one market may have little impact in another. A piecemeal approach to easing constraints may have little to no effect on prices.

Additionally, Glaeser and Gyourko emphasize that in many regions, housing prices do not significantly exceed construction costs, indicating that rising construction costs are a key factor. Data from the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) shows that the average construction cost of a single-family home rose from $124,276 to $428,215 between 2000 and 2024. Industry sources estimate that regulatory costs now account for roughly 25% of single-family housing costs and 40% of multifamily construction costs.

Thus, even if prices align with construction costs in many markets, regulatory costs still play a role via construction costs. This impact can be seen directly in costs through fees, building codes, and other requirements. More fundamentally, as Glaeser, Gyourko, and their colleagues have documented, these regulations also affect construction productivity.

While labor productivity across the broader U.S. economy has grown by approximately 290% since 1950, construction-sector productivity has declined. Incredibly, construction productivity now stands about 40% lower than in 1970. Physical productivity measures, like square feet built per worker, are stagnant at best. Why has construction fallen so far behind?

Glaeser and his co-authors show a link between construction productivity and land use regulation. More tightly regulated cities have smaller, less productive construction firms. If regulatory costs drive construction costs, directly or indirectly via equilibrium productivity, then their impact can far outstrip the effect implied by the markup over construction costs approach. Earlier research points to a hesitancy of homebuilders to innovate in the face of building codes and other regulatory barriers. Glaeser and his coauthors show that this effect can have general equilibrium productivity consequences. Because of these interlocking effects, the impact of regulation on housing costs can far exceed the simple markup observed over construction costs.

Addressing these issues requires more than piecemeal reform. Given the interconnected nature of regulatory costs, state-and federal-level action may be necessary to overcome entrenched local opposition. Preempting local regulatory impediments is needed to unlock greater housing supply.

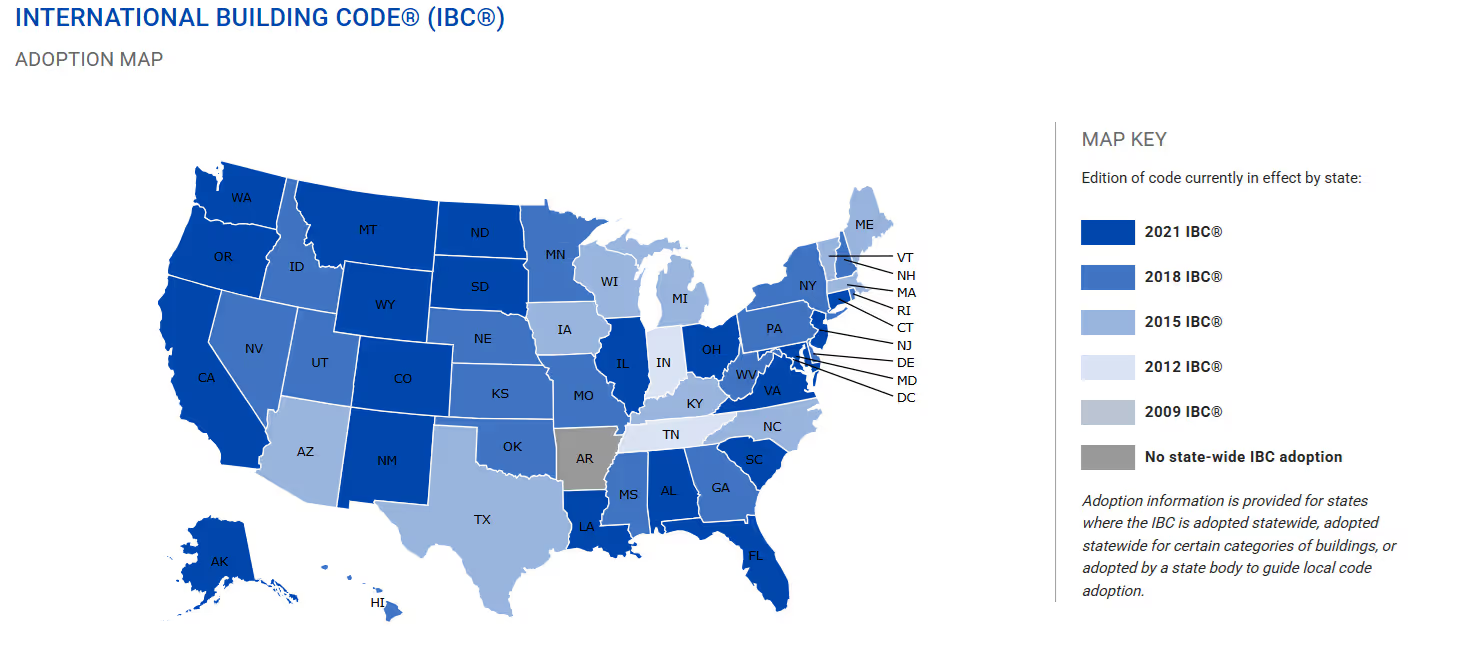

Based on the new research on productivity, one area that may have large returns could be standardizing and modernizing building codes. The current codes differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and recent updates to standards have often focused on potentially costly components like sustainability and energy efficiency. Developing a standard, performance-based, and cost-optimizing code could lead to greater investment in innovation across the industry.

Source: https://www.iccsafe.org/adoptions/code-adoption-map/IBC

Policy design should focus less on numeric production targets or traditional metrics like rent-to-income ratios, which can be misleading. Instead, policymakers should prioritize affordability as reflected in prices and rents.

The stakes are high. Rising housing costs have been linked to declining productivity, fertility, and mobility. These costs also ripple through the broader economy, impeding business dynamism and economic growth. Reducing regulatory barriers and boosting construction-sector productivity is not merely a housing-market issue—it's a national economic imperative.

Dan Shoag is an Associate Professor in Weatherhead School of Management's Department of Economics at Case Western Reserve University.

Economic Dynamism

The War on Disruption

The only way we can challenge stagnation is by attacking the underlying narratives. What today’s societies need is a celebration of messiness.

Unlocking Public Value: A Proposal for AI Opportunity Zones

Governments often regulate AI’s risks without measuring its rewards—AI Opportunity Zones would flip the script by granting public institutions open access to advanced systems in exchange for transparent, real-world testing that proves their value on society’s toughest challenges.

Downtowns are dying, but we know how to save them

Even those who yearn to visit or live in a walkable, dense neighborhood are not going to flock to a place surrounded by a grim urban dystopia.

The Housing Crisis

Soaring housing costs are driving young people towards socialism—only dispersed development and expanded property ownership can preserve liberal democracy.

Blocking AI’s Information Explosion Hurts Everyone

Preventing AI from performing its crucial role of providing information to the public will hinder the lives of those who need it.

Kevin Warsh’s Challenge to Fed Groupthink

Kevin Warsh understands the Fed’s mandate, respects its independence, and is willing to question comfortable assumptions when the evidence demands it.

.avif)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)